By Seamus Murrock

In the afternoon of the 21st of September, bustling trading floors around the world will come to a standstill, ready to sift through Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen’s post-Federal Open Market Committee press release with a fine-tooth comb. For nearly a year and a half, this procedure has been routine at all the largest firms, whose analysts spend hours weighing the merits of a difference between synonymous words such as “optimistic” and “encouraged,” hoping to gain even a morsel of insight from one of the federal government’s most abstruse institutions.

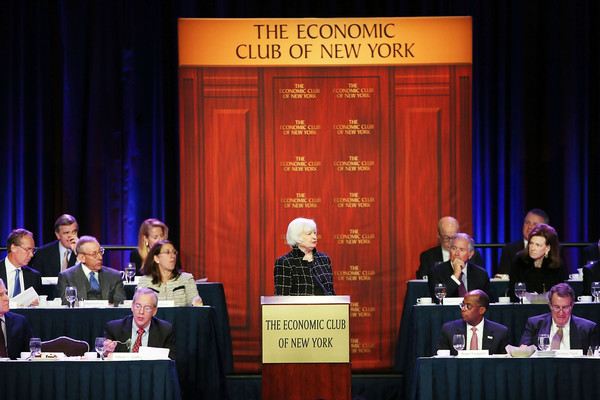

When President Barack Obama appointed Yellen as the 15th Chair of the Federal Reserve, he was right in selecting someone with an extensive background as a labor economist, especially one whose previous stint in Washington came during the economically robust years of the Clinton administration. To their credit, the Federal Open Market Committee, under Yellen’s guidance, has done a superb job of fulfilling the Fed’s so-called “dual mandate” (full employment and steady inflation), with unemployment falling under 5 percent as of May 2016, and inflation gradually rising in spite of a recent slowdown.

Since the financial crisis of 2007-08 began to wind down, however, the Fed’s inability to successfully perform another one of its key functions — the setting of benchmark interest rates — has left portfolio managers from New York to Hong Kong in disarray, wreaking quarterly havoc on the financial markets. In a time where money managers around the world desperately seek certainty and safety following a global recession that many countries are still trying to escape, the Fed has offered very little to investors regarding their plans for raising these benchmark interest rates.

Following several quarter’s worth of encouraging macro data from 2013 to 2015 — like falling unemployment, a steady rise in consumer confidence, and a strengthening U.S. dollar – the Fed began to conduct “live meetings,” or F.O.M.C. meetings, during which an interest rate increase is considered to be on the table. The conferences after these meetings have spurred the obsession over Yellen’s prose and diction. Investment banks, hedge funds, and other large financial institutions all hope to gain insight from Yellen’s words into when the Fed will begin to buy back U.S. Treasury bonds, decrease the nation’s money supply and thereby raise these interest rates.

After months of scrutiny, the benchmark interest rates were raised in December of 2015 to their current level of between 0.25-0.50 percent, following nearly a decade of these rates being essentially zero. While the increase had little effect on large firms’ behavior, the controversy leading up to these meetings pushed market volatility up to levels unseen since the last recession. VIX, a volatility index used to track uncertainty in the markets, spiked up to well over 20 points before four of the last five Fed live meetings, even reaching 40 points ahead of the September 16-17 meeting (anywhere from 10-16 is considered stable). Traders around the world use VIX to measure and react to volatility in markets that otherwise goes unquantified; it peaked around 80 during the trough of the Great Recession.

As a result of this relationship between Fed uncertainty and already-shaky financial markets, many stocks and certain commodities have suffered as investors flock to safer bets like U.S. Government debt and other investment-grade bonds. Uncertainty surrounding the Fed and its interest rates was also one of many factors contributing to the historic sell-off of American stocks to start the year, when the Standard & Poor’s 500 Stock Index plunged over 20 points, or about 9 percent, in a little over a month.

Raising a country’s benchmark interest rates, which are used to construct everything from mortgages to the dollar-peso exchange rate, is generally considered a vital tool to help rebuild an economy mired by recession. An increase in rates particularly enables the country to defend itself against future economic downturns by consequentially lowering said rates. The alternative, as Japan is learning the hard way this year, is to turn interest rates negative after failing to raise them back above zero following a recession. The Japanese government is effectively paying its citizens to borrow money in order to stimulate economic growth, a strategy that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has been forced to publicly defend on multiple occasions. It is also worth noting that, with the last recession ending in late 2010, the historically reliable 6-year recession cycle that many economists use to predict future turbulence foresees another downturn of the U.S. economy within the next year or two.

It is easy to understand Yellen’s argument for abstaining from an interest rate increase: between Greece’s debt crisis, uncertainty in China, and Britain voting to leave the European Union, several board members — including William Dudley of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York — fear that adding an interest rate hike at the wrong time could sink our fragile economy back into recession. The flaw in this reasoning, as many critics point out, is that there will always be another event to restrain American benchmark interest rates. One of the main consequences of our globalized economy is that each nation is hypersensitive to a ripple effect from nearly any type of economic activity, from Greece defaulting on debt payments to oil spills in the Gulf of Mexico. As a result, it becomes more important for the U.S. to be able to use interest rates as a defense against downturns caused by any and all globalized risks.

For much of the past six years, the Fed has been slowly pulling the Band-Aid off of U.S. benchmark interest rates, leaving financial markets around the world squirming in pain. With another recession looming and interest rates still hovering near zero, it is time for the Federal Reserve to force markets to adjust and rip off the Band-Aid once and for all.