By: Russel Abad

Hip-hop is the best-selling music genre worldwide. As an art form that thrives on lyricism over instrumentation, hip-hop is culturally adaptable in even the poorest corners of the world. This makes the genre one of the most powerful platforms for political discourse and activism. While radio rap has many convinced that hip-hop culture is about materialism and misogyny, the truth is that hip-hop was made to empower a people suffering from poverty.

Like all artists, rappers should have the right to make music as they please, but they need to be aware of the impact their work has on the genre and society as a whole. Being such a substantial piece of popular culture, hip-hop directly affects how the youth perceives the world and their place in it. Hip-hop has been a vehicle for minorities and outsiders to both articulate and fix their anxieties. If hip-hop continues to stand for hedonism, people outside the genre will never see the true emotion and activism behind the music. In this sense, it is the moral responsibility for artists to be true to themselves and then to express their art in a way that propels the hip-hop culture forward.

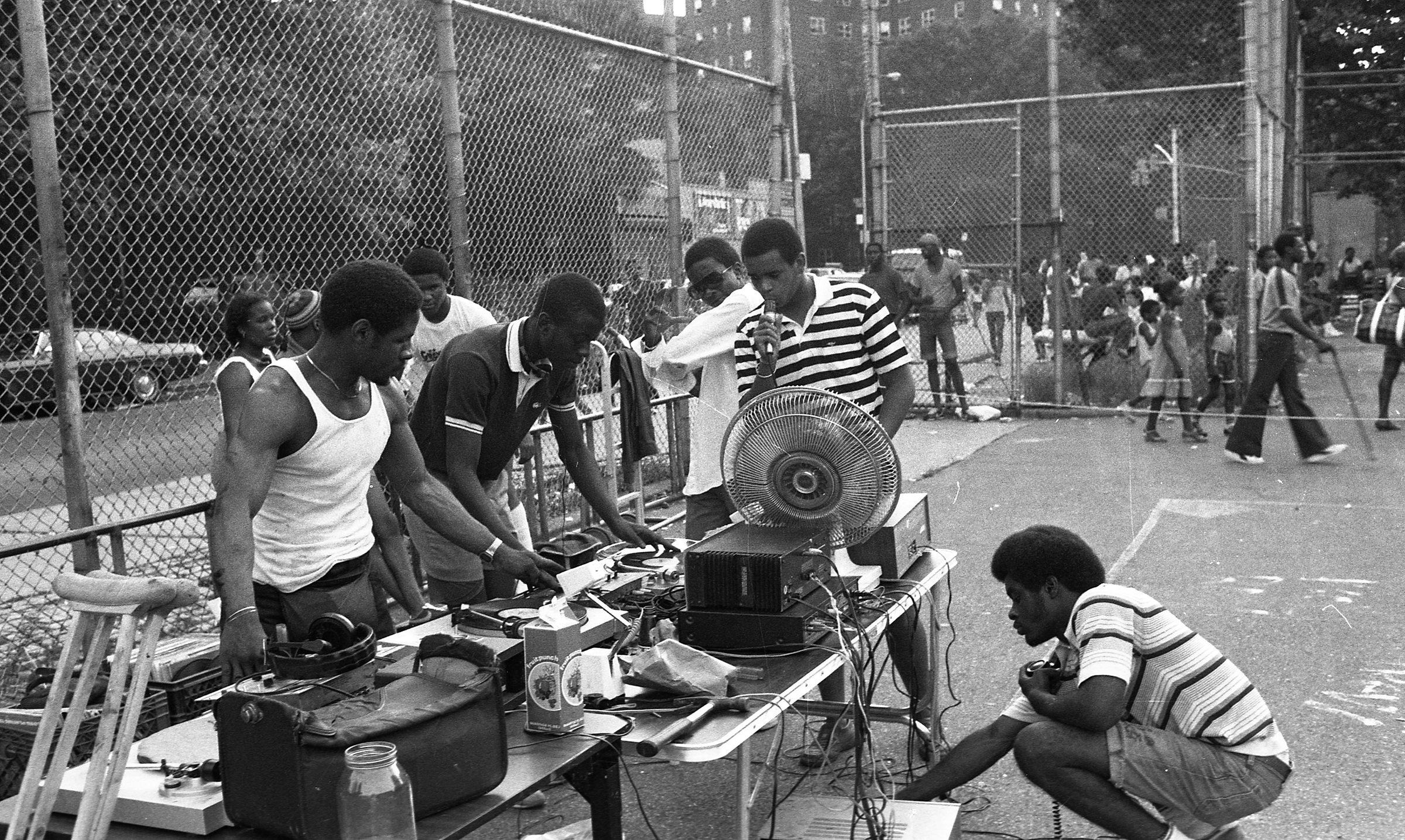

The term “hip-hop” actually encompasses five different forms of expression: rapping or MCing, DJing, break dancing, graffiti art, and the most important, knowledge. The inclusion of knowledge is paramount because it is the basis of the other elements and crucial to the artistic goal of finding meaning in life. These overlapping art forms arose from the need to unify predominantly African-American communities living in the South Bronx during the 1970s.

Hip-hop music builds upon Jamaican reggae and dancehall traditions of boastful singing and poetic improvisation over an instrumental. The American incarnations of MCing and DJing took off throughout the rest of the Bronx and the rest of New York by means of house and block parties. In these early years, hip-hop was able to reduce inner-city violence by funneling the youth’s aggression into competitive rap and break dancing battles.

In 1982, Grandmaster Flash’s “The Message” hit the streets with the first sociopolitical rap hook: “Don’t hold me, ‘cause I’m close to the edge, I’m trying not to lose my head.” These lyrics reflected the everyday struggle and seemingly inescapable pain from living in the South Bronx’s inner-city. The opening verse paints a picture of a neighborhood stricken with poverty, reciting “Rats in the front room, roaches in the back, Junkies in the alley with a baseball bat.” The song’s narrative tells a personal account of a woman who came to the city “so she can tell her stories to the girls back home” but is forced into prostitution to make ends meet and another about a son’s failed education with unsupportive teachers who thinks he is a “fool.” “The Message,” with countless depictions of drugs and crime as a result of poverty, was a precedent for introspection in rap.

A new era of hip-hop formed out of such sociopolitical commentary and became more aggressive and self-assertive. This “new school” of hip-hop took rap music to the mainstream. The formation of white rap group the Beastie Boys in 1981 diversified the face of hip-hop music. In 1986, legendary music producer Rick Rubin teamed up rap trio Run-DMC with rock band Aerosmith, blurring genre lines. The 1980s would be known as the golden age of hip-hop, a time when rap was the most diverse and innovative.

Hip-hop group Public Enemy distinguished themselves with a very brash commentary of politics and criticism of American media. Their song “Fight the Power” is the epitome of this outspokenness and is perhaps Public Enemy’s best-known song. It gained extreme popularity as the theme song to the Spike Lee film Do the Right Thing, a powerful depiction of racial tensions in Brooklyn. The song criticizes racial imbalance within the media, saying “I’m Black and I’m proud, I’m ready and hyped plus I’m amped, Most of my heroes don’t appear on no stamps.” The song also condemns Elvis and John Wayne of racism and replicating African-American influenced music. The song is an affirmation to the black community to stand up for rights and equality.

By the end of the decade, the “in-your-face” attitude turned up yet another notch with the “gangsta rap” movement that took the airwaves by storm. The two hubs for this movement were California on the west coast and New York City on the east coast, spreading rap across the country. The group N.W.A, which brought rap legends Eazy-E, Ice Cube, and Dr. Dre to fame, stirred controversies with songs like “Fuck tha Police” which bluntly protested police brutality and racial profiling. They portrayed the helplessness within their hometown of Compton, California that over the years translated into anger. N.W.A was a controversial faction in music criticized of glorifying gang rivalry, drug dealing, and other crime. However, many gangsta rappers defend these motifs as representations of real-city problems.

Hip-hop music has come a long way since its origins. Today, there are different incarnations of hip-hop specific to subgenre and region, but as a whole one thing that has not changed is the theme of political discourse in urban life. A new term has emerged to describe political rap music: conscious hip-hop. This identifier is often used to label artists of the late ‘90s and early 2000s such as Common, Mos Def, Talib Kweli, and even rap superstar Kanye West.

Hip-hop today has not only crossed international borders but it has permeated entire ethnic cultures. Female English-Sri Lankan rapper M.I.A. supports Tamil nationalism in Sri Lanka and protests American war in the Middle East throughout her catalog. White rapper Macklemore has charted the Billboard charts with “Same Love” advocating gay marriage equality.

Perhaps the most recent artist to merge message and rap music under an international spotlight is Kendrick Lamar. Both Snoop Dogg and N.W.A’s Dr. Dre have formally acknowledged Lamar as the new king of the West. His last album and first commercial success “good kid, m.A.A.d. city” changed the rap game forever. The concept album follows the life of a young Kendrick Lamar living in Compton, gangster rap’s first stomping ground. The purpose of the album was to give back to Lamar’s hometown and encourage Compton youths to choose music, family, and religion over plagues like gang banging. The album’s narrative depicts peer pressure as a central cause for gang violence. It depicts Lamar as a product of a harsh environment that he must learn to fight.

National Public Radio recently created a hip-hop portion within their music department, depicting the degree of hip-hop’s cultural importance. It is bittersweet for some hip-hop fans how mainstream rap music has come to stand for sex and money, but there still is hope. Artists like Kendrick Lamar still dedicate themselves to making music that is rich both as music and as political conversation.