By Cait Felt

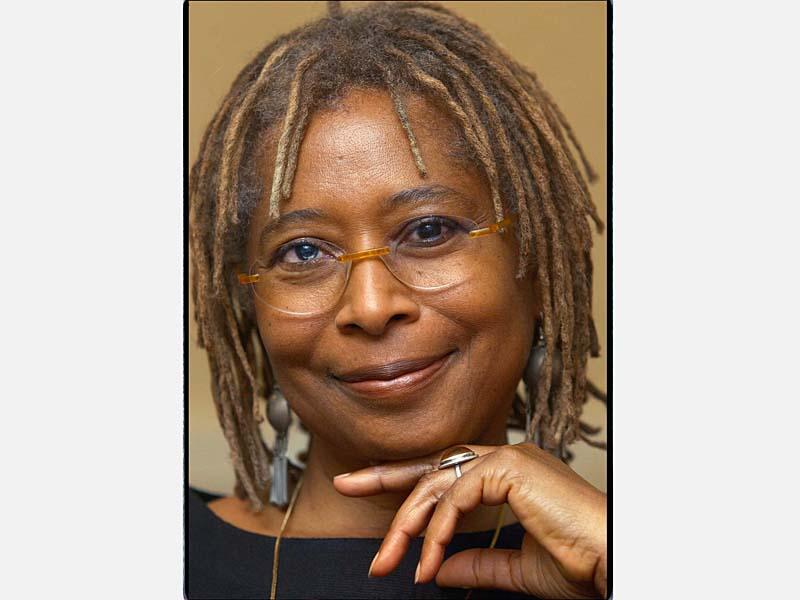

This week, the University of Georgia was honored to host the great Alice Walker, sponsored by the Willson Center for Humanities and the Delta Airlines Chair for Global Understanding. Walker is a native Georgian (though she calls herself “not an American, not a Georgian, but an earthling”), born in Eatonton. The daughter of two African-American sharecroppers, she attended Spelman College and then Sarah Lawrence on scholarship during the 1960s. She made a name for herself as a poet during the Civil Rights Movement, publishing her first book of poems in 1968 under the name “Once.” She later went on to write many famous novels, essays, and poetry collections, perhaps the most famous being “The Color Purple.” She also has won many prestigious awards, including the Pulitzer Prize for Literature.

It comes as no surprise, then, that demand for Ms. Walker’s limited time came at a premium here in Athens. She offered one first-come-first-serve speech at the UGA Chapel on Wednesday October 14th and another ticketed (albeit free of charge) speech at the Morton Theatre Thursday the 15th. Fans had to be turned away at both events due to seating limitations, but even the overflow room with live streaming was filled to the brim with members of the UGA community interested in the legend that is Alice Walker.

Ms. Walker certainly did not disappoint. Her speech at the Morton was entitled “A Conversation with Alice Walker,” and lived up to that name by setting the scene. Ms. Walker sat in an armchair onstage atop a rug and lit by house lamps. She was accompanied by UGA Professor Valerie Boyd, who is working in conjunction with Ms. Walker to publish a curated collection of Ms. Walker’s journals by 2017. Ms. Walker started the evening off by teaching the audience the “butterfly wave.” She prefers to flap her arms against her torso instead of saying goodbye to people because she says the gesture reminds her of the butterfly effect. She said that she likes to remind people that “we may have the power of a butterfly, but we can change the globe.” After teaching her captivated audience about her preferred method of greeting, Ms. Walker and Professor Boyd moved on to the questions of the night.

Ms. Walker began by saying that this visit was the first time that she had been to Athens since 1989, and recalled living with an aunt and uncle in Athens when she was two and her mother was recovering from an injury. She discussed how she enjoyed the renewed feeling of “the energy of being in Georgia, of being in the South really.” Specifically, Ms. Walker discussed the higher population of people of color in the south and that living in California, she sometimes feels “lonely.” She used this as an opportunity to tell her audience how important being with “your people,” whomever those people may be can be to one’s soul. This subject brought her to the importance of ancestors and heritage in her work. She said that she could “feel” her ancestors throughout her body, and referenced the moving musical performance of Voices of Truth before her speech as just one example of the heritage that African-Americans should appreciate for its optimism and deep roots.

When asked about her upbringing and influences on her adult work, she discussed how she was her parents’ eighth child, so they were simply “too tired” to force her to do things like go to church as they had with her siblings. Instead, she spent that time with nature, which she referred to as “my church.” She says that this time as a child really influenced her to be grateful for everything around her. She began to ask “how does anything ever happen?” in reference to her spirituality, which is a common theme in many of her writings. Professor Boyd asked how she managed to keep that childlike wonder alive in her adult years, to which Ms. Walker responded “well, it just happens because I’m in the world… To live in this world is to be enchanted.”

Even in her adulthood, she discussed her “love of adventure” and her perceived fearlessness. “It’s not so much that I’m not afraid,” she said, “but I accept it because I’ve been given the gift of light in this area.” She believes that the toil of her ancestors not only gave her something to pay them back — her happiness and complete dedication — but a light and wisdom even on issues like female genital mutilation, which she has been active on attacking. She says, “we owe these ancestors who’ve endured… and it has to do with showing up… I can’t believe that they would say to us to turn your back on this [hurting] child.”

She also cited the importance of reading in her childhood. In fact, reading young and reading often is the most common piece of advice she gives to younger children in the world today. She said “I started to think of reading as one of the most radical and liberatory things you could do,” using reading as a sort of escape method from her childhood. She insists that “reading is the door to the you that you can become.” Just as important, she says, is to turn off the television, which she sees as poisoning the home today. She argued for limiting children’s exposure to television, and furthermore to “teach them about the manipulation.” For children and adults, she believes that a lesson on heritage is important. She commented that “our history as people of color has been hidden from us,” and recommended two books about the slave trade and early American slavery. She also says that this toil is a “gift” that the ancestors have given people of color—“we can question anything… If we don’t do that, then I feel we’ve wasted a gift that they have given us.”

Reflecting on her life’s work, Professor Boyd asked Ms. Walker about the use of the term “womanist.” Ms. Walker coined the term in “In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens,” revolutionizing the idea of feminism. She used it specifically in reference to African-American women, but the term is used today to discuss many forms of intersectionality. It is the belief that not every woman has the same experience, so there can be no such thing as one cohesive feminism. Instead, factors like race, socioeconomic status, culture, and others must be considered in addition to gender. Ms. Walker says that “the word is ours, not just mine,” and likens the idea to “wanting to wear a dress that actually fits you,” instead of the one-size-fits all approach of 1960s and earlier feminism (what many would now refer to as “white feminism”).

Further reflection brought Ms. Walker to talking about her involvement and activities earlier in life, to which she said “there’s nothing I wouldn’t do again, and honestly do it harder.” She said “the way I am is purely the way I was meant to be, so why mess with it?” when discussing what she calls “a culture of phoniness.” Her major piece of advice was to be yourself and enjoy doing it. “There’s something to be said for just being the flower that you are,” she says, “the joy of just being. That is sufficient.” She used her speech as a call to action about whatever you’re passionate about, because “when we don’t move, nothing changes.”

Photo Credit: Georgia Encyclopedia