By: Cecilia Moore

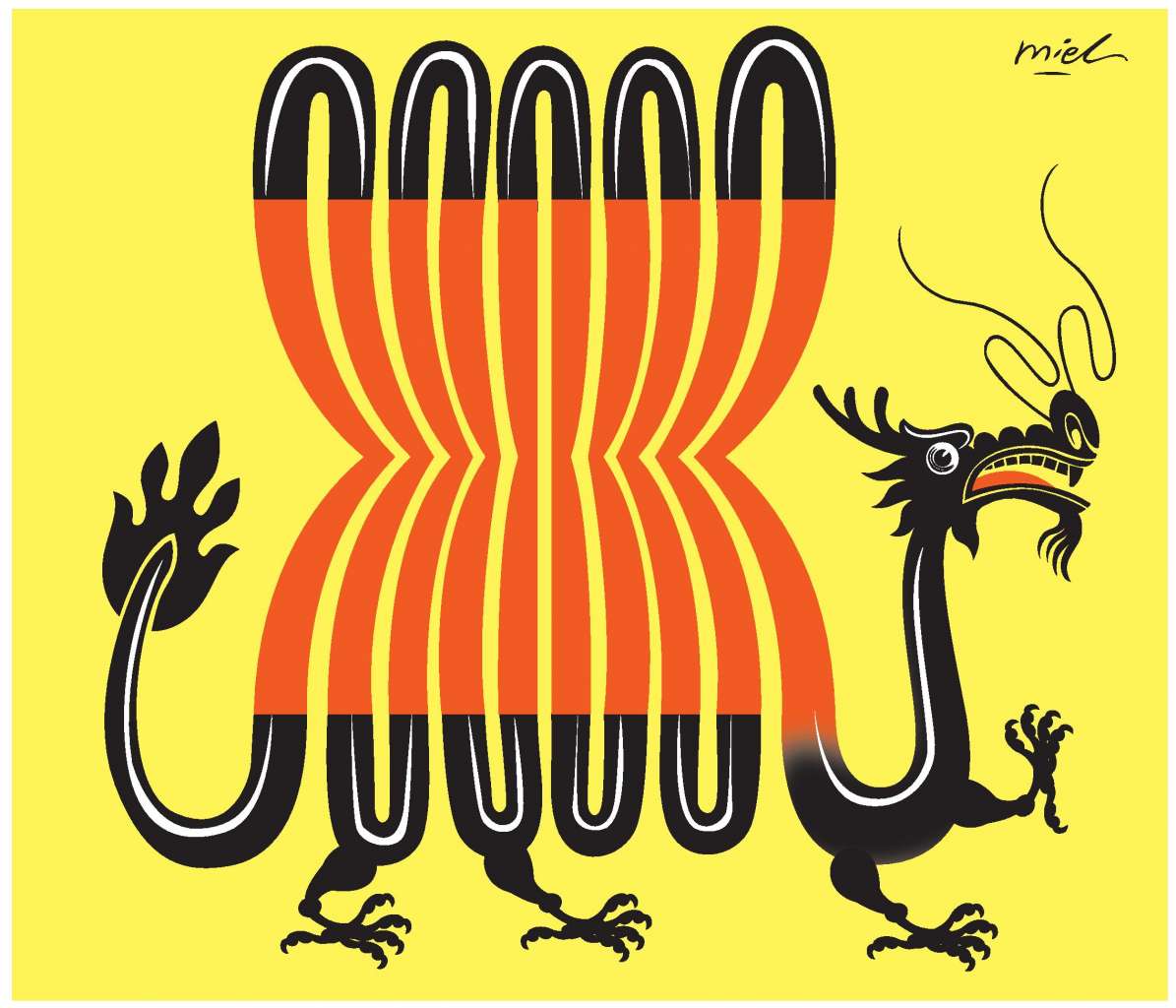

On August 8, four hundred Filipino environmental activists and farmers destroyed an agricultural research plot containing “golden rice”. This strain of rice has been heralded as a solution to the global issue of vitamin A deficiency (VAD), but its journey from the lab to the table has been tedious and replete with public backlash.

Golden rice, which the Filipino government has just this year permitted in five trial plots around the country, has been genetically modified to produce beta-carotene. Beta-carotene, which gives the rice a distinct golden color, is broken down into vitamin A by the human body. This vitamin then plays an instrumental role in the development of children’s eyesight and in their overall growth. The absence of this micronutrient from many children’s diets is why VAD is the leading cause of blindness and malnutrition in kids worldwide. Nearly 500,000 youths go blind and an additional one million die as a result of VAD every year. Sadly, this deficiency affects a significant portion of the population in at least 122 countries, most of which are developing nations.

The Filipino government has long been aware of this issue, as VAD affects nearly 40 percent of the country’s children under 5-years-old. Since the Philippines’ International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) was established in 1960, it has spearheaded funding for the development of new rice species that hold promise of being more cost efficient and nutritionally enhancing. In addition to the IRRI, an international team of scientists backed by the company Syngenta was especially interested in developing a beta-carotene producing breed of rice beginning in the 1980s. In 2000, as a result of this combined research, golden rice was finally made a reality.

Although the grain holds potential in being a treatment for VAD, it has not been met with open arms. International environmental groups such as Greenpeace have been hotly opposed to the acceptance of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), including golden rice, due to concerns over the products’ effects on the environment. However, more important to the local Filipino farmers, including those who raided the field earlier this month, is the question of whether or not this strain will actually benefit farmers. According to the IRRI, there are 200 million rice farms in Asia, most of which are smaller than one hectare. Thus, a huge number of Asian’s livelihoods are dependent on the price of rice. If they were to switch to a GM breed of rice for the sake of increasing their regions’ vitamin A levels, would they have to pay a higher price for the seed?

Patented seeds have become a major issue in farming over the last two decades, and the biggest and most controversial name in the seed industry is Monsanto. The conglomerate’s GM corn, soybeans, and cotton have proven to be more cost efficient and have produced higher yields than normal seeds. Yet, because its seeds are patented, farmers who use the company’s products have to buy new seed every season instead of saving a portion for next year’s crop. Now, the added benefits of the seeds’ vitality are being outweighed by its initial price. These frustrations are highlighted in an interview of Bert Autor, who is the leader of the environmental group that led the raid earlier this month:

Agrochemical TNCs, which are protected and abetted by the US government, gained millions of profit from GMOs even at the expense of the health and livelihood of Filipino farmers and consumers… Farmers who shifted to GM corn farming suffered the most, as the price of GM seeds and other inputs skyrocketed. The farmers are now in debt, most of them lose their land to corn traders… Once Golden Rice is commercialized, this will only lead to the privatization of our rice. Agrochemical TNCs have been waiting for this opportunity, to finally control the rice seed industry… as rice is the staple of Filipinos and the people of Asia.

The Filipino rice farmers are weary of falling into this cycle, especially with their continents’ main food source. The Supreme Court ruled earlier this year that farmers within the United States have to obey the rules of Monsanto’s patents, simple as that. Golden rice has an added dimension to regular GM foodstuffs, though. It was created with the intent of solving a serious condition that leads to the deaths of a million children every year. Similar to the fight over the cost of HIV/AIDS medication, when it is literally a matter of life or death, and victims can’t access treatment because they can’t afford it, are heavily protected patents morally just?

This debate is reminiscent of the controversy surrounding Plumpy’nut. Plumpy’nut, a fortified peanut butter paste, has been very successful in treating children with acute malnutrition. And since the 2005 famine in Niger, during which the product kept 60,000 children alive, its demand has steadily increased. Nutriset patented Plumpy’nut soon after its creation in 1997, and since then, many have accused the company of keeping the supply of Plumpy’nut low in order to maximize profits. In 2010, Nutriset created the Patent Usage Agreement, possibly in response to the negative press it received over its ardent protection of the patent. The company argues that it has never supplied less than the demand, and it now points to the co-ops Nutriset started in a number of African countries through the Patent Usage Agreement as proof of the company’s humanitarian objectives.

There may still be hope for golden rice. Following in the footsteps of Monsanto, the Syngenta and the inventors of golden rice have patented the grain. However, in a move similar to Nutriset they have also created the Golden Rice Humanitarian Board. This board, which is within the framework of the Golden Rice Project, will oversee the dispersal of the grain to countries with high levels of VAD, and its creators promises “free access for those who need it,” including those in the Philippines.

Even though golden rice is being promoted and funded by the country’s IRRI, and its dispersal is being overseen by an organization that is humanitarian in nature, there is still strong dissent from the Filipino public over the grain’s use. This may stem from a lack of accurate information about the product. Unlike some GMOs like AquAdvantage Salmon, which grow twice as fast as regular salmon and are inherently unnatural sounding, golden rice is similar to bio-fortified foods, which are foodstuffs that are naturally enhanced with vitamins and minerals. Golden rice is not harmful to humans, and it is not expected to have an abnormal affect on the environment. Golden rice isn’t the solution to malnourishment—consistent, well balanced diets are. However, it could substantially decrease the significance of VAD in developing countries around the world until these peoples can afford better diets. Thus, it is time that the Filipino farmers lay down their pitchforks and begin nurturing fields of golden rice.