By James West

On September 24th, the elections for the German federal parliament, the Bundestag, took place. By the end of the night it was clear that German politics had undergone a dramatic shift in the past four years. But this shift may primarily be one of appearances and not of true change for the country.

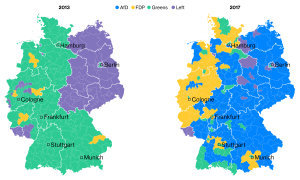

The German electoral system works through a mixture of first-past-the-post and proportional representation. Simply put, a party must secure at least five percent of the national vote in order to be eligible for any seats allotted by proportional representation in the Bundestag. For this reason it came as a shock to many that Germany’s notorious far-right party, Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) not only managed to win the parliamentary seats it had been denied in the 2013 election (when they won only 4.7% of the vote), but gained over twice this minimum percentage.

AfD won 12.6% of the vote in the latest Bundestag election, translating to 94 seats, or 13.3% of the Bundestag. This may seem to be a landmark victory for the European far-right, but the realization quickly sank in that this amounts to little. As the Washington Post put it, “The five parties that control the remainder of the seats in the 709-member Bundestag have said they will not cooperate with the AfD and have denounced the party’s anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim rhetoric. That makes the AfD’s chances of actually using its perch in the federal Parliament to enact legislation minimal, at best.”

In another article, the Washington Post noted that the German political system is very good at containing minority parties (and opinions), pointing to the fact that the AfD’s role in parliament boils down to what is called “controlled opposition”. The key here is that minority parties in the Bundestag typically make their voices heard through coalitions with other parties – and no other parties want to harm their reputation by associating themselves with the far-right.

In other words, the AfD exists not as a true “alternative” for German politics, but as a vehicle for the European far-right to vent out its frustrations with the modern political system – without actually effecting any real change. Supporters of Alternative für Deutschland are allowed to vote, express their opinions, and even see representatives of their viewpoints sit in the seats of the Bundestag, but despite the excitement of the Western media over this, they have won nothing but more of the same leadership.

Upon closer examination, the AfD does not even present itself as a proper alternative for German politics, even if they did possess real political power. The party’s short history has been riddled with inconsistencies in policy and unprofessional behavior by its representatives. The latest news shows that former Alternativ für Deutschland leader Frauke Petry has been charged with perjury, and has left the party because of the chaotic disorganization among its senior members.

Another aspect of the German federal system is the election of the Chancellor by the Bundestag and not by direct vote of the German people. In practice, this means the largest party or coalition in the Bundestag always chooses the Chancellor, and it is common practice for parties to choose their nominee for the office well ahead of the actual vote. This is how we know that the incumbent Chancellor, Angela Merkel, has secured for herself a fourth term by the victory through plurality of her Christian Democratic Union (CDU/CSU). But the CDU/CSU only received 32.9% of the votes this year, down from 41.5% in 2013, making this the lowest vote they have received since the election in 1949.

Merkel has held the chancellorship since November of 2005, putting her at nearly twelve years already in office and now on track for a total of sixteen. This is an unusually long time in office for a Chancellor, and by the end of this term Merkel will be on par with Konrad Adenauer (who served as Chancellor after the end of WWII) and Helmut Kohl (who served as Chancellor during the reunification of East and West Germany). Those were chaotic times for Germany that marked historical transformations of the German government. It would be in the best interest of Germany and the world to ask what transformation is now occurring, and what the German government will look like when Merkel’s era concludes.

We can see in many cases the healthy skepticism of the Western media in the face of other world leaders who have served unusually long terms, maintained power despite low popularity, or actively silenced political opposition. After the Syrian elections of 2014 saw incumbent president Bashar al-Assad secure another term in a country torn by civil war, Western media were quick to denounce the elections as a “farce”. One can be sure that if Russian President Vladimir Putin, who has already served for many years, were to secure yet another term in the upcoming 2018 election that the media would investigate this thoroughly. In fact, recall the recent fears in America over rigged elections, both by now-President Donald Trump before the 2016 election, and by his opponents, before and after his victory. Questioning outcomes such as these is key to maintaining a truly democratic society.

But in the case of Angela Merkel, the Western media are not asking these questions. Merkel has managed to hold office for this many years despite her plummeting popularity, role in the German migrant crisis, and the accompanying attacks that have occurred again and again… and again and again and again. Her initial push for a limitless influx of migrants into Germany proved so unpopular and destructive that she and her party are now finally beginning to shift their stance: “Joachim Herrmann, the CSU’s top candidate, argued: ‘There must be a clear upper limit of refugees in Germany.’ He said that his party ‘is not willing to do without it.’” Non-Western media has noted Merkel’s decidedly un-democratic attitude, as she has made it one of her goals to silence the opposition voice of the democratically elected representatives of Alternativ für Deutschland.

Simply touting the ideals of liberal democracy should not be enough to convince the world that Merkel is a truly democratic leader. It is the established political system which has kept her in power through elections which are left unquestioned – less than a year after the integrity of the American electoral system itself was thrown into question over allegations of foreign influence. Despite the conviction of many that the German far-right now has a say in national politics, this could not be further from the truth. Strong opposition to Merkel’s policies is both silenced by the atypical exclusion of a minority party from the coalition system, and is denied an authentic voice when the only option is a party both unprofessional and prone to extremist views. We can conclude from this that those who tried to strongly oppose Merkel in this election had their efforts and votes diverted into a non-effective party, and that democracy was reserved only for those willing to vote the way the established political system wanted.

This phenomenon is not exclusive to Germany, either. Earlier this year we saw all of France’s right-wing political frustrations diverted into the campaign of Front Nationale, yet this amounted to nothing in terms of change in the French government. In fact, the only reason we can even see evidence of these views in post-election Germany is because of the unique structure of the German Bundestag. As Huffington Post put it,

“In fact, Macron’s victory reflected a political system that encourages majorities by holding run-off elections. That disguises rather than eliminates support for the extremes. In Germany a system of proportional representation ensures such backing is translated into Bundestag members.”