By Michael Momayezi

As he arrived in Paris to close several business deals with French companies, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani was greeted by thousands of French human rights activists and exiled Iranians protesting his visit. The moderate president who was once hailed as a symbol for progressive change in Iran has come under fire in recent months for failing to improve Iran’s human rights record as the country has witnessed a marked increase in executions throughout his term. As Rouhani reaches his third year as president, many wonder if the man who ran on a platform of reform and anticorruption will do anything to combat human rights abuses carried out by the state. Is he focusing on stabilizing the Iranian economy first, or is he, as Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu put it two months after Rouhani’s election in 2013, “a wolf in sheep’s clothing?” Or perhaps even more frightening, is he simply unable to do anything about it?

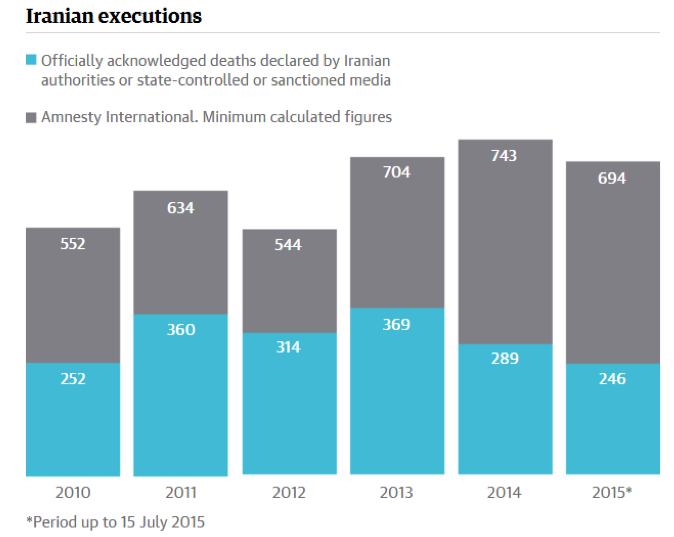

The unquestionable spike in executions is quite dramatic; Amnesty International estimated that in 2014, 743 people were executed, nearly 200 more than the 544 executed in former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s last full year as president in 2012. Understandably this has caused much concern throughout the international community, calling into question Rouhani’s sincerity as well as his ability to carry out the terms of the nuclear agreement that was signed last summer. Rouhani’s regime has proven disappointing to many Iranians and human rights activists around the world who hoped that resolving the nuclear issue would open the door to improving human rights in Iran.

These doubts of Rouhani’s true commitment to reform in the realm of human rights reflect in many ways the criticisms of Iran’s last reformist President Mohammad Khatami, who served from 1997 until 2005. Under the Khatami regime, Iran also witnessed an increase in executions as we see today under Rouhani.

A look at the fractured domestic politics in Iran may shed some light onto why top-down reform has seemed to be nearly impossible over the years despite reformist rhetoric coming from the president. While Rouhani is a popularly elected president, he does not hold the same authority in government as presidents in Western democracies do. Above him sits Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who acts as both the political and spiritual embodiment of the ideals laid out in Iran’s theocratic constitution. He has the power to appoint his own allies to various powerful positions in order to promote political cohesion and ensure that policy stays in his favor as much as possible. Among the many positions that the Supreme Leader appoints is the head of the judiciary, who subsequently appoints the head of the Supreme Court and the chief prosecutor. In such a system, those who are loyal to the Supreme Leader, or at least toe the political line, are the ones responsible for convicting and sentencing people to death.

However, what has motivated the judiciary to approve so many more executions since Rouhani’s start as president? One of Rouhani’s major promises to the Iranian people was a process of reconciliation with the West and a lifting of the sanctions that had so crippled the Iranian economy. The thought of change under Rouhani understandably has caused unease in the hardline upper echelons of Iranian government, which has seen itself lose relevance in the political scene – especially among Iran’s huge population of people under 30 that has grown tired of decades of strict governance and global isolation. In the wake of Rouhani’s success at the negotiating table with the West last summer, this fear has become a reality.

To counteract Rouhani’s international popularity and perhaps even his popularity at home among progressive Iranians, Rouhani’s domestic opponents have taken drastic measures to send clear signals to the world that Rouhani is not necessarily in charge. One of these signals included the conveniently timed execution of Mohsen Amiraslani for heresy in September 2014 after nine years of imprisonment just as Rouhani arrived at the United Nations headquarters in New York. Even more, in October 2014, the head of the judiciary gave Gholam Hussein Mohseni-Eji, a man famous for a lack of judicial restraint and impartiality, the power to decide whether or not to execute people based on drug offenses. His strict nature caused the majority of drug offenders sitting on death row to be executed in the months following his appointment.

The recent capture of 10 American sailors, which took place only days before the freeze on Iran’s nuclear program was set to begin, may also speak to the desire of some factions within the Iranian government to humiliate Rouhani’s government, despite the Supreme Leader’s begrudging official endorsement of the nuclear deal. While the terms of the deal have not changed, Iran’s hardline factions have succeeded in other ways; Rouhani’s international human rights image has been severely tainted. As we have seen in the protests in France, such an image threatens Rouhani’s international credibility and may affect future business deals that he attempts to make with the West.

The confusion over Rouhani’s reformist appearance and Iran’s rising number of executions comes from a fundamental misunderstanding of how politics in Iran work. The widespread tendency to label a state’s government as the president’s “regime” could not be further from reality in the case of Iran. When the Supreme Leader, president, legislature, Revolutionary Guard and judiciary are all clumped together and labelled as the “regime”, the multiplicity within Iranian politics is completely overlooked. While many may expect the president to take firm action on human rights in the West, such an expectation is unrealistic in the context of the Iranian government when the political rivalry between the president and the judiciary is as profound as it is. Such a split in power makes one wonder: who’s really in charge?

Since this article was originally written, Iran has gone through national parliamentary elections in which a Rouhani reformist coalition won all 30 seats representing Tehran in the national parliament. More significantly, reformists won 15 of 16 seats representing Tehran in the Assembly of Experts, the body responsible for electing the next supreme leader upon Khamenei’s death. Even more, the longtime hardline chairman of the Assembly, Mohammad Yazdi, was not reelected. While this election will not result in immediate change due to Khamenei’s life-term as supreme leader, it does signal growing domestic confidence in the direction Rouhani is trying to push the country and perhaps the eventual election of a progressive supreme leader.