The first Monday in October marks the end of the Supreme Court’s summer recess. Following a year in which the court handed down landmark rulings with vast political implications (Obergefell v. Hodges, which legalized same-sex marriage, and King v. Burwell, which upheld the legality of a critical portion of Obamacare, among others), it is hard to imagine another term with equivalent political consequence. However, the slate of cases already on the court’s docket, Evenwel v. Abbott in particular, may galvanize politics once again.

Equal representation is the basis of a democratic government, however until the early 1960s “silent gerrymanders” engendered political districts with vast population disparities. California’s senate districts in the early 1960s, which had a standard deviation of 900,000 people, exemplified the egregious population deviations among voting districts that were once commonplace across the United States. In Baker v. Carr, 1962, the Supreme Court decided to “enter into the political thicket” in an effort to preserve the integrity of voting. In distorted voting districts, a district with 200,000 people versus a district with 2,000 people for example, the voters in the district with a smaller population have more political clout because their votes are comparatively “worth more.” That is, fewer voters can decide an election. The Baker decision, in which the court determined that redistricting cases were justiciable under federal courts, initiated the redistricting revolution.

Redistricting questions following Baker initially revolved around which voting districts needed to be redrawn. The court’s decisions in Reynolds v. Sims and Wesberry v. Sanders mandated that the districts for both houses of a bicameral state legislature and United States Congressional districts had to be drawn according to equal population. While these decisions mandated redistricting be considerate of population deviations, it was not explicit how “equal” the districts must be.

The question of equality in redistricting practices has rearisen with the Supreme Court agreeing to hear the case Evenwel v. Abbott. While an abundance of Supreme Court precedents have been devoted to ensuring that population deviations are as minimal as possible, the appellants in Evenwel argue the fundamental baseline of these decisions is flawed. Sue Evenwel challenges that in order to achieve substantive equality, the citizen voting age population (CVAP) of a district should be the baseline for redistricting practices rather than total population, which is the current practice.

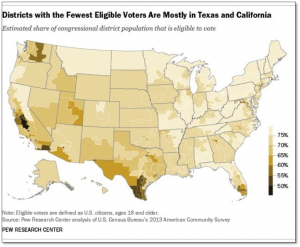

Evenwel resides in a rural Texas voting district, and argues that because a higher percentage of rural residents are registered to vote, her vote is diluted when compared to an urban voter’s vote (see the following figure). The disparity between the two measures, CVAP and total population, is the members of the population who are ineligible to vote – namely illegal immigrants, children, and felons. Evenwel’s argument rests on the fact that urban voting districts have much higher concentrations of those ineligible to vote, hence redistricting according to total population dilutes the comparative influence of rural voters by allowing fewer urban voters to decide election outcomes in their districts.

Redistricting cases have revolved around the equality of total populations since the 1960s when redistricting became mandated. According to Dr. Charles Bullock, a UGA professor and renowned redistricting expert, “If the Supreme Court comes down in favor of Evenwel, it will initiate a flurry of redistricting questions that the court will have to address. This decision has the potential to ignite a redistricting revolution akin to the one in the 1960s.”

This decision carries the potential to have unparalleled political ramifications. A decision in favor of Evenwel could significantly alter the political landscape by instigating a “power shift almost perfectly calibrated to benefit the Republican Party.” Because urban populations have higher concentrations of immigrants and children, a switch to CVAP over total population would transfer power to suburban, whiter areas. In essence, cities which are generally safe-havens for democratic candidates would see voting power shift to more republican strong-holds. Democrats stand to lose greatly in a decision for Evenwel, “Of the 20 districts with the fewest eligible voters in them, Democrats have representatives in 19 of them.” A ruling in favor of Evenwel could drastically alter the make-up of state legislatures and the United States House of Representatives.

While the Democratic Party stands to lose at the benefit of Republicans, the biggest loss would be to those ineligible to vote. Legislators are supposed to protect the interest of everyone in their districts, but “according to analysis of census data by the California Civic Engagement Project at the UC Davis Center for Regional Change, counting only eligible voters would mean that nearly a third of the U.S. population would lose legislative representation.” This is the crux of the issue in Evenwel: whether or not the equal protection clause requires legislators to represent the interest of those ineligible to vote such as children – or if equality on a “per-vote” basis is more important.

The Supreme Court has decided to hear the controversial equal protection question of Evenwel v. Abbott in attempts to clarify the meaning of “one person, one vote.” Along with Evenwel, the court will hear other politically significant cases throughout the 2015-2016 term. A previous case regarding affirmative action in college admissions (Fischer v. University of Texas at Austin) has returned for a court decision. Public employee unions will also appeal before the Supreme Court in attempts to continue collecting money from those they represent through collective bargaining (Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association). The court has not yet completed its docket, but cases involving abortion and the death penalty are sure to reach the court as well. However, the political ramifications of the Evenwel decision are massive. A ruling in favor of Evenwel would assuredly reduce the amount of urban voting districts (generally Democratic) and increase the amount of suburban and rural voting districts (generally Republican). While on its face the case may not be as politically consequential as Obergefell or Burwell was last session, a closer review reveals that a decision for Evenwel could drastically alter the partisan balance in nearly every state legislature and in Washington.

Photo: Pew Research Center