While everyone seems to have an opinion on the topic of refugee acceptance and resettlement in the current political climate, few consider the children that make up over half of these 12 million refugees. Not only have they been uprooted from their homes and seen things that no child should have to experience, but their education has also been put on hold for an indefinite amount of time as their families traverse national borders and await the granting of refugee status. On average, refugees fleeing violent situations like that in Syria are displaced from their homeland for 20 years, which effectively exceeds the length of a refugee’s childhood. The years lost jumping between refugee camps until finally settling in another country or returning to one’s homeland could spell the end of a child’s educational aspirations, as no consistent educational opportunities are feasible during these years of unrest. For those fleeing Syria, many parents worry that their children’s lack of schooling will result in a “lost generation” of uneducated adults who will not be able to innovate or secure specialized jobs, and ultimately be unable to rebuild Syria after the fighting ceases.

The neighboring countries in which these Syrian refugees first settle after fleeing their homeland, such as Turkey and Lebanon, have had the longest amount of time to deal with the educational needs of the refugee children. However, due to their own lack of government stability, many have been unable to adequately address these issues.

Lebanon, for example, has accepted over a million Syrian refugees this year, half of them under the age of 17. Unfortunately, the Lebanese economy was not prepared for the dramatically increased labor supply, so the majority of refugee children are forced to spend their days in the fields rather than in the classroom because their parents are left without jobs. It is easier for children to find work because the few jobs that are available are seen as too low in status for men as the head of the household. As a result, many employers for manual labor jobs will not hire adult men or women, so children end up being the main breadwinners of their families.

For the few parents that can find work, they are still unable to send their children to school. While public schooling is free in Lebanon, the cost of books and transportation to and from refugee camps is prohibitive for most. In some cases, families choose to pay for only one of their children to attend school, and that child will return to the camp to teach the other children what they have learned.

All of this, however, is not to say that no Syrian refugee children are able to receive education in Lebanon. For the 50 percent of primary school-aged and 4 percent of secondary school-aged refugee children, Lebanon has instituted a second shift system that allows Syrian children to attend school in the afternoons following their Lebanese counterparts. The goal is to eventually have the younger children attain a level of literacy in both Arabic and French that would allow them to integrate into the Lebanese classroom without issue. Until then, the Lebanese government aims to simply have all school-aged children in school by 2021. While this doesn’t seem feasible with the steady influx Syrian refugees and lack of employment opportunities, government subsidies for the costs of education or the establishment of temporary schools in refugee camps could remedy the situation.

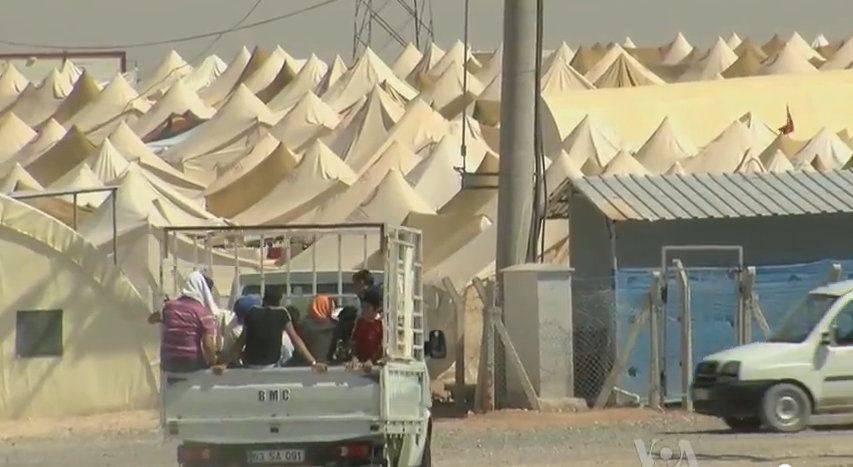

Just north of Lebanon, Turkey has accepted over 2.7 million Syrian refugees in 2016, the most out of any other country in the world. In comparison to Lebanon, Turkey has been much more successful in integrating refugees into society and the education system even though it has been receiving refugees for the same amount of time. Turkey was much better suited to accept this many refugees, as it offers more opportunities and a higher geographic capacity for refugees to obtain permanent housing and jobs than in Lebanon. Because of this, Turkey has far fewer tent cities than Lebanon, and therefore better access to public schools for Syrian children. In 2014, the Turkish government established temporary education centers that partner with Syrian refugees who were teachers in their homeland to teach students, using Syrian curriculum according to Syrian educational standards, until a more long-term solution can be reached. This may perhaps be the most practical and immediate solution to the problem of maintaining educational opportunities, as children feel more comfortable in the classroom and can pick up where they left off in Syria rather than having to learn an entirely new language and educational culture in Turkey.

Now that the refugee crisis is becoming too large for countries surrounding Syria to bear, European countries have begun accepting a growing number of refugees. Since these countries have not had the same amount of time to bolster their education systems, Europe is now reeling from this influx.

In Greece, refugees have been coming in waves from Turkey and surrounding nations, but with economic and governance issues of its own, the country has had considerable difficulty effectively integrating refugee children. Recently, more and more refugees have realized that Greece will not just be a temporary stopover on the way to Germany, France, or the United States due to the lengthy asylum process and have begun enrolling their children in Greek school. Upon hearing that refugee children would be put in the same classrooms as Greek children, Greek parents revolted, insisting that their own children’s educational success would be severely hindered by their Syrian peers. While Greece has yet to come up with a solution that appeases Greek parents, it has begun temporarily offering second shift classes for refugee children. This program has not been in effect long enough to accurately gauge its effectiveness.

As President Obama has pledged that the United States will take in 110,000 more refugees in the next year, it is imperative that we as a nation begin discussing how to handle the influx of refugee children into our schools. While President-elect Trump touted a no-amnesty stance on Syrian refugees during his campaign, he may soften his view as he gets closer to taking office, just as he has on his anti-immigration wall policy involving Mexico. Regardless of whether Trump stays true to his policy regarding Syrian refugees immediately upon taking office, a substantial amount of those 110,000 refugees will likely have already entered the United States and started to integrate into American schools. For the sake of the educational well being of these first refugee children, it is still incredibly important that our education system have some sort of provisions in place to account for these children. We have numerous examples to look to across the world, but must be sensitive to our own country’s attitudes towards Syrian refugees as well as the cultural differences in our approach to education as compared to Middle Eastern countries. Given the proper attention and preparation, we can provide these students with opportunities that will allow them to achieve their individual educational goals, as well as empower the next generation of Syrians to rebuild their war-torn motherland.