By: Dillon Causby

For most of the 20th century, Scottish politics mirrored the rest of the United Kingdom (UK), being split between a center-right Conservative Party and center-left Labour Party. By the 1970s, however, a new party emerged that turned Scottish politics on its head: the Scottish National Party (SNP). Unlike the Conservative or Labour parties, the SNP is neither right or left wing and advocates for a Scotland independent from the UK. Since the late 2000s, the SNP has been able to capture voters from across the political spectrum and dominate Scottish elections.

However, since 2020, the tide seems to have turned on the SNP. Support for the party in the polls has slowly declined, and so has public enthusiasm for the party’s ultimate goal, Scottish independence. In the face of this waning support, commentators are once again asking if this is finally the end for the SNP.

However, this isn’t a novel prediction: Over the past 50 years, the death of Scottish nationalism has been declared again and again by the British press, but it has always managed to survive. The SNP is not a “flash party,” which rises quickly before disappearing forever. It is the product of a post-industrial, secular Scotland, and has profited off of the decline of institutions that previously defined Scottish politics. Despite being successful in this new Scotland, internal division, exhaustion, and the resurgence of old competitors are threatening its position. If the SNP is to retain its relevance, it must find a way to reaffirm party unity, reignite enthusiasm for Scottish independence, and create a clear alternative to a Conservative- or Labour-led Scotland.

An Unlikely Success Story

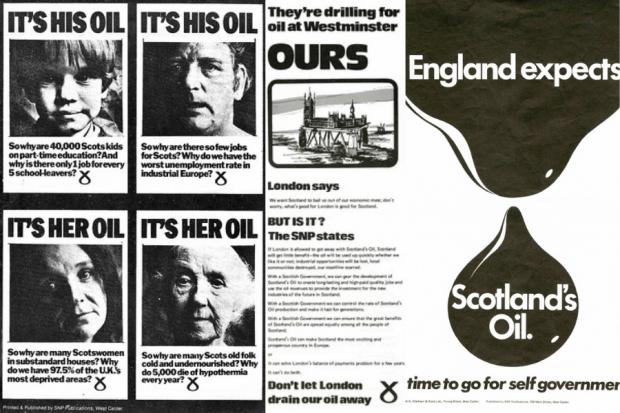

The SNP was founded in 1934, 227 years after Scotland was united with England and Wales to become the UK. Until the late 1960s, Scottish independence was a romantic, yet unserious, ideal. However, the party grew rapidly in the 1970s, winning 11 seats in the House of Commons in the October 1974 elections. This sudden success is usually credited to the discovery of North Sea oil. The “It’s Scotland’s Oil” movement, an SNP media campaign demanding that oil revenues be devolved to Scotland, convinced many Scots that the country should have more autonomy over political and economic affairs.

After the 1970s, the SNP’s prospects can best be explained by the party’s lack of institutional linkages to churches, trade unions, and other civil society organizations. As explained by Gregory Baldi, the Conservative and Labour parties, which dominated Scottish politics until the 2000s, had strong institutional ties to the Church of Scotland and the Trade Union Congress, respectively. In the 1980s, the SNP’s lack of institutional linkages made it difficult for them to establish any base of support. However, as other parties’ institutional linkages frayed in the 2000s, the SNP was able to capture disaffected voters and mobilize them around the goal of Scottish independence. Although these voters might have disagreed on economic or social issues, they were united by a desire for Scottish autonomy.

Party Troubles

The breakdown of traditional linkage institutions is a major factor in how the SNP was able to become Scotland’s largest party. Although they lost the 2014 independence referendum, the SNP continued to win elections on both the regional and national level, dumbfounding political commentators. However, since Covid-19, this era of dominance has waned. The party’s support among Scots has steadily declined, and so has support for Scottish independence, falling from 53 percent in August of 2020 to 44 percent in September of 2024.

This decline can be attributed to a few factors. Firstly, the SNP is experiencing internal divisions over sociocultural issues, specifically transgender rights. Admittedly, this is not a new problem for the SNP. As explained by Vernon Bogdanor, a professor of political science at Gresham College, the SNP, like other nationalist parties, are neither purely left or right wing. As a result, the party has had to accommodate many differing viewpoints that often come into conflict with each other. Secondly, the SNP’s main adversary, the Labour Party, has experienced a resurgence after a decade in the political wilderness. This is due to a general desire among Scots to prevent a Conservative government in Westminster. Lastly, since losing the 2014 referendum, the SNP has deliberately downplayed Scottish independence in favor of other issues. This tactic, while once electorally successful, has had a strong demobilizing effect among party activists who could previously be relied upon to campaign at elections and advocate for party positions.

What’s Next?

By any appearance, the SNP is in dire straits. The party is facing internal strife, reinvigorated opposition, and an unmotivated base of support. Nonetheless, their position is not hopeless. Many of the seats lost by the SNP in the last general election were lost by very close margins, and since the general election, the SNP has once again surpassed Labour in opinion polling. Furthermore, although support for Scottish independence has decreased, there is still a sizable block of the Scottish public that wants independence.

Any gain in support from the SNP will most likely come from a loss in support for Labour. On the whole, Scotland is much more left leaning than the rest of the UK. As the Labour government in Westminster tacks to the right, many within the SNP are hoping to capitalize on public frustration towards the central government. In fact, this happened in the 2000s, when Scottish voters, disillusioned with the Labour government, decided to throw their support behind the SNP. As British Prime Minister Keir Starmer continues to advocate for social spending cuts, there are signs this could happen again.

This does not mean, however, that renewed success will fall into the party’s lap. If the SNP is to survive, it must resolve its internal divisions and reinvigorate its disillusioned base. How the party will resolve these issues remains an open question. Nonetheless, it is certain that if the SNP does not change, its downward trajectory is likely to continue for the foreseeable future.