By Lauren Sung

On March 1, 2020, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) released a report that stated over 80,000 Uighur Muslims were forced by the Chinese government to work in factories that supply 83 multinational corporations, including Nike, Zara, Apple, Adidas, Amazon, and Sony.

It was already known, with a United Nations committee bringing forth reports of mass imprisonment and other forms of discrimination, that the Uighur Muslims in China were forcibly detained in re-education camps for indoctrination purposes under the guise of deradicalization and job-training; The Chinese government has attempted to explain these camps as a means of combatting the threat of terrorism and anti-government sentiments among the Uighur population. The number of ethnic Uighurs kept in such centers is numbered at over a million since 2017. Xinjiang, the province in northwest China where Uighurs make up 45% of the population, is under constant surveillance by the Chinese government and local police departments, with the use of AI technology for the specific purpose of identifying and tracking Uighurs and tens of thousands of new police officers patrolling the streets. The ASPI report has brought the human rights abuses against Turkic ethnic groups in China into the public eye once again.

Commendably, the United States House of Representatives passed a bill titled “Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act,” which aims to condemn and end the mistreatment of Uighur Muslim communities in China, including “arbitrary detention, torture, and harassment.” Various human rights organizations, such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, have also criticized the current practices. Yet the oppression of Uighur Muslims should not be considered resolved. Not only is it unlikely that China will easily obey the demands for more humane treatment of its ethnic minorities, this is just one example of the human rights abuses observed in countries throughout the world that can be tied to the influence of multinational corporations. The news of forced labor in China should be recognized as a continuation of the government’s suppression of ethnic and religious minorities, but it also points to a glaring inability for multinational corporations to engage in responsible regulation. Human rights abuses in factories are far from new, and the outsourcing of labor to countries with less regulatory oversight is one oft-cited consequence of increasingly globalized supply chains. In fact, according to the International Labor Organization, around 21 million people are victims of forced labor as of 2012.

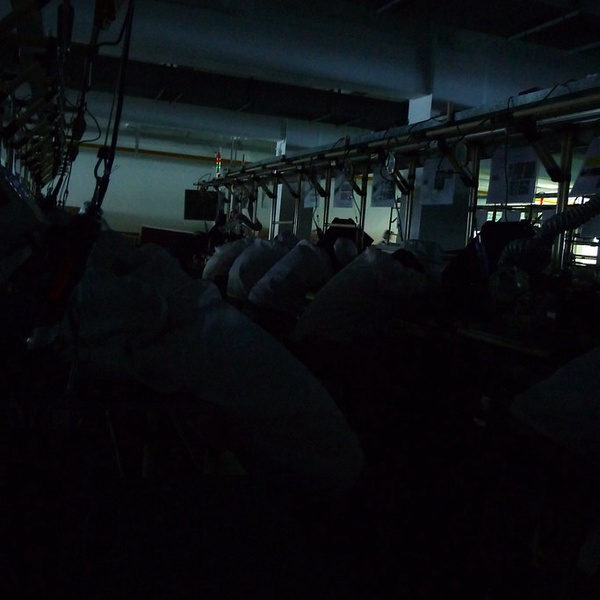

The forced labor of the Uighur Muslims is not a new case of business malpractice but rather the continuation of a long trend for which multinational corporations must be held accountable. The lack of proper regulatory practices and a general lack of transparency has allowed for these inhumane conditions to continue across the world. It should come as no surprise, then, that the companies that benefit from the forced labor of Uighurs in China are also known for child labor, low wages, and unsafe working conditions. Factories across many countries including China often pay little, do not permit independent unions, and maintain dangerous working conditions.

Of course, both the Chinese government and the corporations being supplied by such factories are to blame for this violation of human rights. As recommended by ASPI, China must protect the rights of all its citizens, especially as a fast-growing economy that needs to compete in a market that increasingly demands more ethical practices. For China to comply with the calls for greater social responsibility, however, international organizations and foreign governments must exert pressure so China will comply with international law. Despite criticisms from the aforementioned rights organizations and the statements from over twenty countries calling on the Chinese government to uphold its laws, the general failure of the global community to ensure that China complies with its own labor policies points to the ineffectiveness of purely rhetorical reactions.

Simply condemning the actions of the Chinese government is not enough. There must be some consequence imposed onto China outside of mere criticism to bring about genuine and lasting change. While sovereignty is important, it should be considered only ethical that countries respond more forcefully to the state-sponsored oppression of Uighurs than it is at the present. Countries could, for example, place sanctions on products thought to be made in factories that make use of forced labor or engage in more public diplomatic processes to exert more pressure on China.

While there is no easy fix for the subpar working conditions that can be found in many supply chains, corporations must be held accountable for the factories that create their products. The United Nations has examined corporate involvement in human rights issues and asserted that multinational corporations have a responsibility to respect the universal rights of people in the countries that they operate in. In no way does any person or institution deserve to profit from human rights abuses, and the fact that these multinational corporations are likely to experience continued growth is morally abysmal.

The corporations implicated in ASPI’s recent findings ought to be more transparent and to thoroughly investigate the factories which have been accused of using forced labor. Should companies publish an adequate and complete list of factories which manufacture their products, for example, it would be a step in the right direction. It would also be ideal for those companies to investigate and suspend their activity in those factories. Target, Adidas, and Esprit, as a start, stopped purchasing textiles from one of the factories located in a Xinjiang internment camp last year; hopefully, this trend will continue for the dozens of other factories that benefit from forced labor. China must allow those investigations. Governments and multinational corporations share a responsibility to maintain the basic rights of all people, and the current failure of the status quo at addressing China’s persecution of ethnic and religious minorities must be addressed.