By Aashka Dave & Hammad Khalid

In an ideal world, epidemics would never happen. Barring that impossibility, epidemics would be resolvable, and sources would be identified and contained, as was the case in London 160 years ago.

Great Britain in the 1850s was a conflict-heavy nation. Indian citizens had started revolting against British colonial rule, which would eventually lead to the dissolution of the Mughal Empire. The Crimean War was about to begin. In the United States, Bleeding Kansas had just begun, and Abraham Lincoln was rapidly rising from small-town lawyer to prominent politician.

On the home front, Britain was struggling with a new scourge: cholera. Dr. John Snow, an obstetrician with an investigative bent, had long believed that contaminated water was the source of cholera outbreaks. Politicians and peers were less than receptive to these claims, despite the fact that cholera spread worldwide in the 1800s, causing a pandemic of the worst sort. Snow consequently sought a way to prove his detractors wrong, and became the father of epidemiology, or the study of diseases, in the process.

Cholera first reared its ugly head in Britain around 1831, when Snow was fresh out of medical school. Between 1831 and the 1854 outbreak in London, tens of thousands of people died. Most doctors at the time believed that cholera was caused by breathing a “miasma in the atmosphere,” or inhalation of noxious, disease-carrying air. As such, cholera would have been impossible to contain, much less eradicate. While it is true that some diseases are airborne, it is decidedly not the case for diseases such as cholera and Ebola.

Snow began to investigate the differences between those people afflicted with the disease and those without it. He contrasted the habits of the afflicted and the healthy, and cross-referenced those habits with his own hypothesis about water contamination. Eventually, having established that diseased individuals obtained water from a pump on Broad Street, and that individuals without the disease obtained water from a pump in Soho, Snow was able to take his research to town officials. He convinced them to take the handle off the pump on Broad Street (believed to have been contaminated when a mother washed her baby’s diaper in a town well). Since no one could use the contaminated pump, new cases of cholera abated. Snow had set his reputation in stone.

The technologies and research methods in the employ of modern epidemiologists far eclipse those available to Snow. However, both Snow and epidemiologists of the 21st century are concerned with the etiology, or origins, of any given disease. Diseases are classified based upon their prevalence in any given community. A disease is therefore endemic to a region when it exists permanently in a region or population. It only reaches the level of an epidemic when the numbers of actual instances of a disease far outpace the expected occurrence of that disease. The pandemic level is reached when a disease is spread on a global scale. The Black Death, which killed a quarter of Europe’s population during the 1300s, is likely the most famous pandemic to date. The 2003 outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome is also considered a pandemic, as it spread from Hong Kong to several other countries courtesy of international travel.

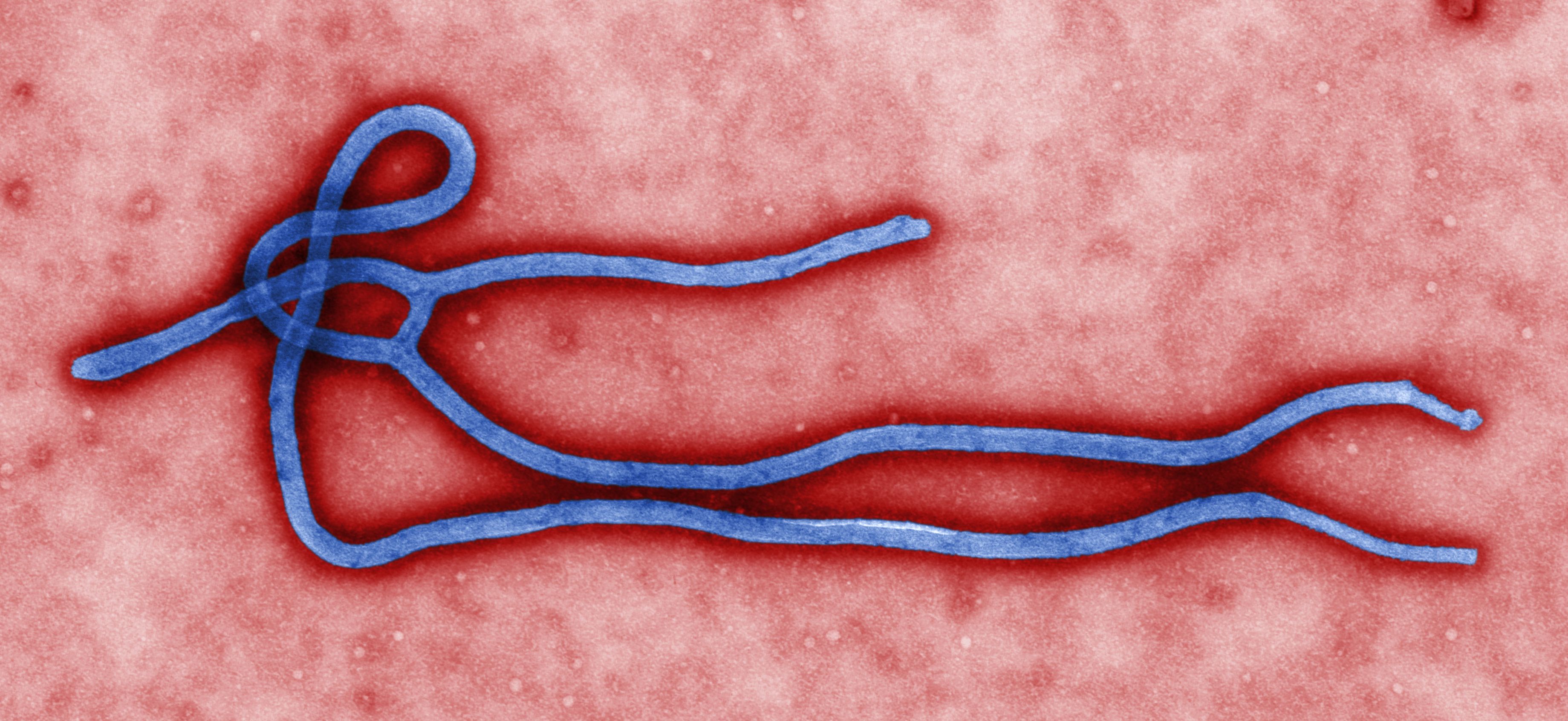

Today, the world stands in awe of a different disease: Ebola. Unlike SARS, Ebola is not an airborne disease. Rather, Ebola is spread through physical contact with body fluids including, but not limited to, saliva, sweat, and tears. If you have a cut on your hand, and shake hands with a sweaty Ebola victim, it is entirely possible to become infected. As such, it is easy for Ebola to spread, particularly in those regions with poorer sanitation practices.

Yet, that a February outbreak in the small West African nation of Guinea could spread so far so quickly has taken the world by surprise. By all accounts, this is the deadliest Ebola epidemic ever recorded.

Ebola hemorrhagic fever is a human disease caused by the Ebola virus. The disease is usually acquired when a person comes into contact with the blood of an infected animal such as a monkey or fruit bat. Once a human is infected, contagion is highly likely through direct contact with bodily fluids. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the virus can take anywhere from two to 21 days to incubate and cause symptoms. Therefore, an infected individual may not know that he or she has been infected until a future date. Symptoms typically include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle pains, and headaches, while the fever and internal bleeding attendant to the disease cause death.

Over 5,300 cases of Ebola have been reported in Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Nigeria, and Senegal, including over 3,000 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. This particular strain of Ebola virus, known as the Zaire strain, originated in Guinea and has a 90 percent mortality rate. While there have been other Ebola outbreaks in the past, this case seems especially perilous for multiple reasons. Even though Ebola does not have a cure or vaccine, mortality rates drop dramatically with early medical intervention. However, in countries like Guinea, where medical infrastructure is poor, the spread of a disease can be rapid and devastating.

The international attention bestowed upon West African countries afflicted with Ebola is bringing deeply-rooted societal problems to light, including a lack of healthcare education, as evidenced by a widespread fear of Ebola and subsequent refusal to accept medical care from international relief organizations. This refusal of medical aid is caused by a variety of factors. Some are mistakenly associating the appearance of foreign medical professionals with the presence of Ebola. In other words, they are falling prey to the common logical fallacy of “correlation proves causation” by believing that health workers are somehow causing the Ebola virus to spread.

Fear of health workers is perpetuating the rapid spread of the disease, creating a second crisis. When villagers flee at the sight of a Red Cross truck screaming, “Ebola, Ebola!” as they run, it is no surprise that health workers are having trouble enforcing the containment of the disease.

In fact, the hostility against foreign medical professionals has grown so much in West Africa that workers say they are now battling resentment and aggression in addition to the deadly Ebola virus. Medical professionals from organizations such as Doctors Without Borders and the World Health Organization have been threatened with stones and machetes. Vehicles are surrounded by hostile mobs. Log barriers across dirt roads block health workers from reaching villages where medical attention is needed.

Some West African social and cultural practices may also be expediting the spread of the virus. For instance, the stigma associated with contracting Ebola discourages patients from seeking medical attention that can help them overcome the infection in its early stages. Furthermore, certain funeral practices that involve touching the deceased may be accelerating the spread of the disease.

Although medical care is urgently needed, it is also crucial to address the relevant public health aspects of the outbreak, such as informing Africans about proper prevention methods. After all, the best way to survive the disease is to avoid infection in the first place. The Ugandan government has made efforts to address the stigma of Ebola by creating a network of survivors to educate the public about the disease. Hopefully, with additional similar measures that replace fear and misperceptions with concrete knowledge, the outbreak will have a greater chance of successful containment.

The recent Enterovirus 68 outbreak in 45 U.S. states has proven that the developed world is not immune to epidemics, though. While strains of enterovirus circulate every year, this year has seen a spike in the number of children affected. The first cases were reported to the CDC last month in Kansas City and Chicago. Since then, over half of all confirmed cases in those two cities have been children with a history of wheezing or asthma, according to Anne Schuchat, the director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. The virus has likely been spreading quickly as children go back to school and mingle with thousands of their potentially-infected peers. Since its symptoms mimic those of an intense cold, parents are unlikely to notice the severity of the disease for some time.

Even though there is no antiviral treatment or vaccine for Enterovirus 68, the good news is that early September is peak season for enteroviruses. Consequently, physicians expect the number of infections to begin leveling off. As of this writing, there have been four deaths linked to the virus, according to the New York Times. Regardless, parents can prevent the virus from spreading by reminding their children to practice standard hygienic procedures such as frequent hand washing.

Unlike Enterovirus 68, Ebola does not spread easily in regions with high sanitation practices and prolific health communications. For one thing, Ebola can only be passed on by an infected individual who is exhibiting symptoms. Given that an infected person with symptoms in the United States would be isolated almost immediately, the chances of the disease spreading are minimal. Furthermore, the U.S. population is receptive to the advice of healthcare professionals. Suggestions made by organizations like the CDC are likely to be adhered to. Quite frankly, the chances of catching Ebola in the United States are far slimmer than the chances of dying on a rollercoaster. Cases of Ebola will appear in the future. However, Ebola will not become an epidemic in the United States.

Diseases cannot be eradicated under most circumstances. Smallpox is the only disease to have been completely obliterated to date, a testament to the scale of the task at hand. That being said, the outbreak of any given disease, and the potential it holds to become an epidemic or pandemic is a daunting prospect on its own. Diseases carry with them grim prospects and portend fear far and wide. Health promotion and communication are therefore of the utmost importance in preventing and containing epidemics of all kinds, ranging from cholera to Ebola.