By Torus Lu

Immigration policy has featured significantly in the 2016 presidential election. Proposals have ranged from deporting every illegal immigrant to providing them with a healthcare plan. However, there is one noteworthy effect of American border policy that receives scant attention: migrant deaths.

Several thousand migrants have died attempting to cross the U.S.-Mexican border in the last two decades. In 2015 alone, U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported 240 deaths along the border. In the Tucson sector, which covers a 262-mile portion of the southern border of Arizona, migrant deaths often number over a hundred every year.

There are numerous factors that lead to migrant deaths. An obvious one is the migrants themselves. After all, they are the ones making the decision to cross the border, and many are doing so illegally. Nevertheless, a narrow focus on illegal immigrants’ responsibility leads to no decent solutions. One might as well wish that the motivations behind immigration – massive gaps in economic opportunity and drug violence – disappear.

Another way to look at the issue is to examine the cause of the problem. These deaths of migrants are primarily caused by environmental variables: exposure, heat, and dehydration claim the most lives. It makes sense, then, that most of these deaths occur in locations like the harsh Sonoran Desert in Arizona and California, but what is less obvious is why illegal immigrants choose to enter through some of the most inhospitable regions of the American Southwest. The answer lies in where the U.S. Border Patrol concentrates its forces.

In its 1994 National Strategic Plan, the Border Patrol adopted a strategy of “prevention through deterrence”, concentrating Border Patrol resources in urban population centers to disrupt traditional migration flows. It became standard procedure to leave the remote areas less secured. The end goal of this policy was to deter illegal immigrants from crossing, but the end result was that the common migration routes now ran over mountainous and desert areas. Terrain- and climate-related crossing difficulties were insufficient to reverse the trend in illegal immigrant population growth, and thus risks to illegal immigrants rose significantly. Deaths spiked.

More recently, there has been a greater emphasis on counter-terrorism efforts along the borders. After the September 11 attacks, the Border Patrol was reorganized from a Department of Justice agency to a Department of Homeland Security agency. The post-9/11 reorganization also added a mission of “preventing terrorists and terrorist weapons from entering the United States”. The concern was that large illegal immigration flows could be exploited by terrorists for easy entry into the United States.

Newer reports also indicate a general discontinuity in the way Border Patrol resources are distributed. The 2004 National Border Patrol Strategy declared that it would continue building its enforcement strategy around the “prevention through deterrence” policy, focusing on deterring migrants from crossing through urban areas. While the 2012-2016 Border Patrol Strategic Plan did not directly mention this policy, the Border Patrol document “Holding the Line” finds that there remain large variations in the level of enforcement at different points on the border. Furthermore, it finds that the concentration of Border Patrol resources in urban areas was accompanied by increased crossings in less-controlled areas.

In response to the rise in deaths, the Border Safety Initiative began in 1998. Safety measures adopted included public notices warning about crossing dangers, search and rescue operations, and training of agents in providing emergency care. While the initiative certainly had concrete successes in saving migrant lives, this over-arching border policy placed the Border Patrol in the peculiar role of chasing the people they were trying to save. Further complicating the role were reports of abuses by Border Patrol agents against detainees, as documented by the advocacy group No More Deaths. Interviews alleged denial of food and water, inhumane detention facilities, and physical assault.

Civilian initiatives to reduce migrant deaths have also seen some success. The group Humane Borders has established water stations as a method of preventing dehydration along the U.S.-Mexican border. The Tucson Samaritans regularly have volunteer teams patrolling the desert to deliver water to those in need. No More Deaths operates desert camps for the purpose of providing water, food and medicine.

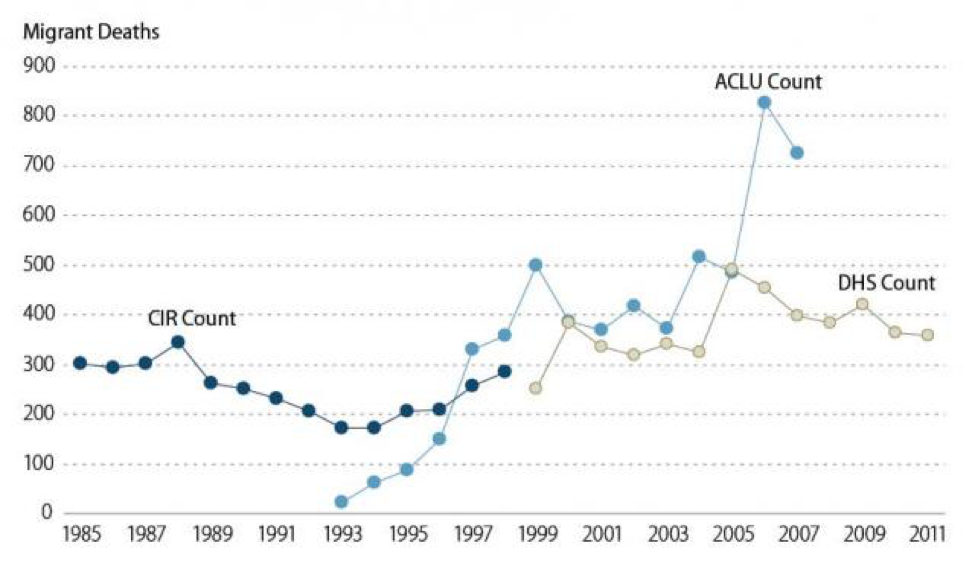

Relatively speaking, the number of migrant deaths in 2015 represented an improvement. According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s statistics, there has been a sustained decline in migrant deaths since 2012, and 2015 had the lowest level of migrant deaths since 1999.

However, it would be unwise to conclude that crossing the border is now safer. The recent decline in migrant deaths has come at a time when illegal immigration has also declined. According to Pew Research, the population of illegal immigrants from Mexico peaked at 6.9 million in 2007 and has declined to 5.6 million in 2014. According to the Border Patrol, apprehensions of illegal immigrants along the U.S.-Mexican border — often considered a proxy for the level of illegal migration — also decreased in 2015. Thus, it is likely that the reduction in migrant deaths is due to a reduction in the number of migrants rather than the rate at which migrants die.

Furthermore, there is some evidence pointing to increased mortality among migrants. In the Tucson sector, the ratio of migrant deaths to migrant apprehensions has doubled from the next deadliest year on record.

It would also be unwise to place too much emphasis on specific numbers. Migrant death counts along the U.S.-Mexican border are difficult to measure. Individual deaths enter the record when remains are discovered in the vast region and after medical examiners place an estimate on the time of death. These estimates can be imprecise on the order of years. Further complicating the issue is that counts vary widely based on the organization doing the counting. For example, the American Civil Liberties Union reported over 800 migrant deaths in 2006 while the Department of Homeland Security reported less than 500 in the same year.

Regardless of what the exact numbers are, migrants continue to die attempting to cross the border, and they do not seem to be entering the general political conversation surrounding immigration. Perhaps migrant deaths are ignored because they are seen as a form of punitive justice: a migrant is entering illegally, so they deserve anything that happens to them. Perhaps these illegal immigrants are seen as a tradeoff: their presence must lead to damage to America’s economy, security, culture, or general well-being, so it is in America’s interests that they do not arrive alive. Or perhaps those deaths are simply the price paid for the important goal of homeland security. As long as political discourse remains within these lines of thinking, policymaking will continue to avoid addressing migrant deaths.