By Melanie Kent and Carson Aft

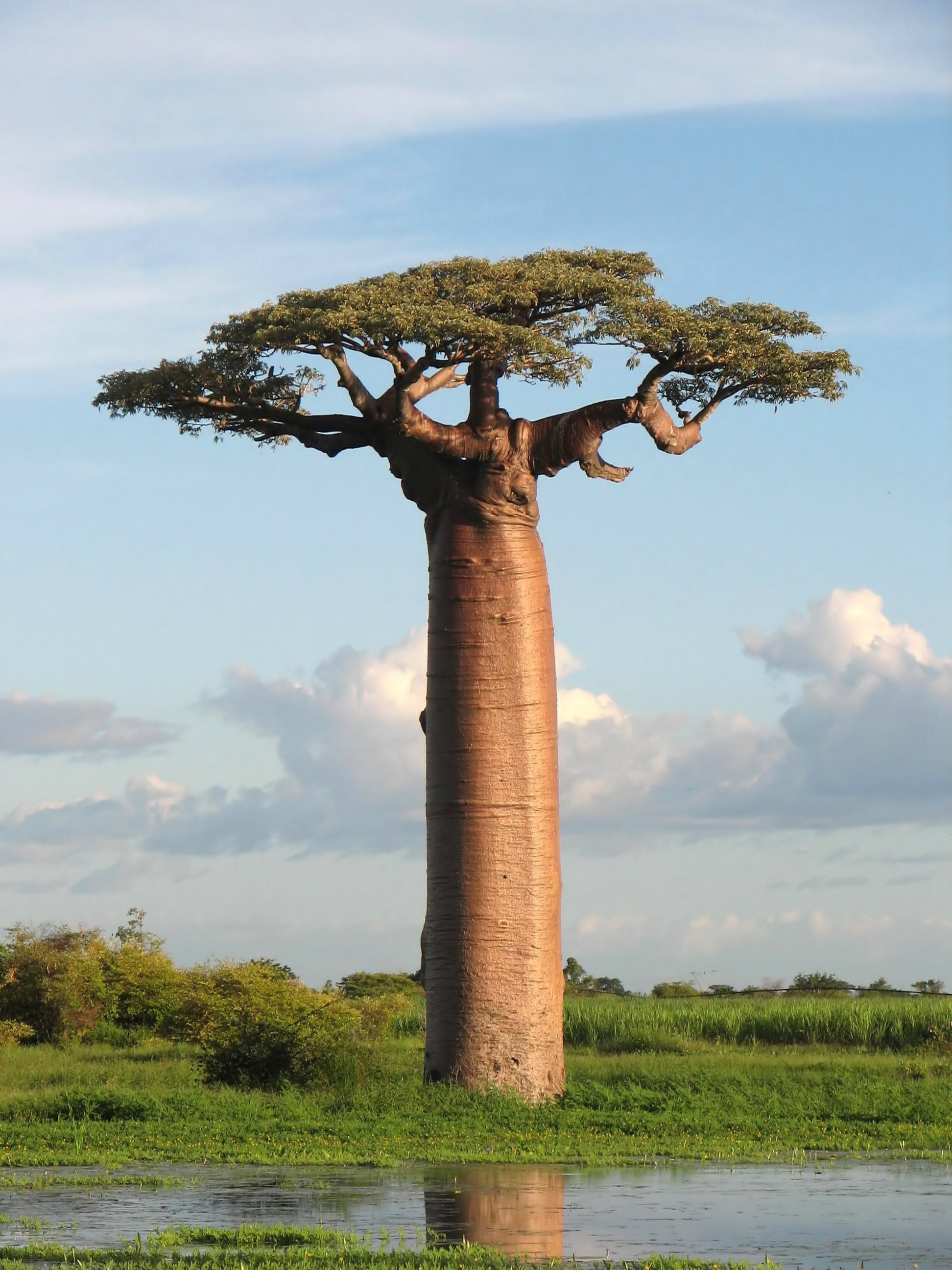

The scene is rural Kenya, in the rolling hills dotted with baobab trees, lush with vegetation and sprinkled with straw-thatched huts. In the distance are the shining metal rooftops of the border town where business intersects with the marginalized poor. Struggling areas of the world such as this one have been left behind by globalization and pilfered by agents of capitalism. It is this setting that attracts the charitable aid of the West for its ragged children, uneducated mothers, and AIDS-infected fathers. Helpless without international aid, these victims of disease, famine, and conflict need the benevolent and neutral aid of the messianic West. Left in the shadow of commerce and growth, sorrow blooms.

Modern corporations are portrayed as a blight. Infinitely hungry and insatiably expanding, they seem to seek profits baptized in exploitation, groping blindly from country to country. Hefty dividends cannot differentiate between the efforts of unions and children. The toils of freemen are the same as the indentured. The citizens of the world only see the harsh juxtaposition of the Congo’s mighty green forests being carved for the mighty green dollar, and it does not sit well with them.

The opposite end of the spectrum from the image of the dollar-hungry corporation is the nonprofit. Nonprofits, charities, and foreign aid organizations exist for the generalized purpose of making things better, whether that means entertaining the masses, feeding the poor, or saving lives abroad. Relinquishing greed, they argue, allows for focus on the important things, thereby maximizing the good that can be done. Rather than worrying about how large the profit margin is, these groups can worry about how many people they are helping. There are no shareholders for charities. But, despite their altruistic intentions, do charities truly provide all the help they intend?

To call nonprofits angelic could be an overstatement. Real halos are fragile, and frequently these companies can betray the good they are sworn to. The strong rhetoric begins to break down when the actual results of all of this altruism are examined. There is a massive difference between charity and foreign aid having great intentions and having great outcomes.

Both disaster relief and many types of developmental charity have side effects that can mean life or death for both individuals and economies. On the extreme negative end, humanitarian aid can prolong violent conflicts by providing care and resources for the warring parties. As an example, both developmental and emergency aid have fed armies and supported warlords in Ethiopia and Cambodia. The prospect of receiving aid has in some cases caused the deliberate creation of humanitarian disasters. In Sierra Leone, rebels and government soldiers intentionally created “cut-hands gangs” to attract foreign attention through the press coverage of amputees. In Somalia, food aid was attracted through political instigation of localized famines.

Aid can also flood markets by “dumping” goods, which can undercut local production. In areas where corn is produced, for instance, large donations of the grain cause prices to drop locally; this in turn destroys the ability of local growers to compete. More indirectly, outside provision of goods and services can prevent those capacities from ever being developed on the ground. For example, physicians who fly in to provide medical care and bring supplies with them make local production of those goods and services unnecessary in the short term. Native professionals aspiring to work in medicine or community building leave for more fruitful locations, preventing sustainable indigenous services from developing. Even outside of an assisted region’s market, large inflows of donated goods can artificially cause prices (and exchange rates) to increase across the economy in what is called the “natural resource curse” or “Dutch disease.” Other sectors of the economy lose productivity as well. In the spirit of giving, charity too often takes.

Aid may be given in monetary form to national governments as well. These large donations in many cases do not end up aiding the intended recipients, however, because of corrupt governmental practices. Officials court aid organizations for financial assistance and, in many cases, put the fruits of this labor into their own pockets. Even into the 21st century, governments in developing countries are overwhelmingly funded by foreign aid (up to 70 percent for some including Rwanda, Mali, and Sierra Leone). Many of these countries are ruled by despotic and inept dictators who, by using foreign money for their own ends, further drag down nations they lead.

Consequently, the practice of placing foreign aid directly into the coffers of corrupt governments undermines good governance. Leaders receive their pay not from the taxes of citizens to whom they are accountable, but from donations. As a result, politicians are not accountable to their citizens because their governmental positions and own financial security are not contingent on the satisfaction of their constituents. Aid destroys the proper functioning of a democratic system much like oil funds in petroleum-rich countries support the autocrats in power.

The demonized straw man that is the modern corporation deserves redemption. In contrast to the caricature so often thrust upon businesses, it is impossible to generalize the motives of all firms around the world. Even if every single company only sought profits, that quality would still fall short of a sin. Although it is easy to characterize them as such, earnings and the corporations who seek them are not evil, even though it seems they are playing the role of villain in a Disney movie. The archetypal conglomerate is always polluting the environment, bullying children, or tearing down the homes of adorable old men. Interestingly, fiction is fake.

Capitalism also provides opportunities that charity cannot. Malaria, the great scourge of the tropics, is now curable. Thanks to innovation and invention, worldwide mortality rate for the plague have fallen 42 percent since 2000, according to the WHO. The infrequently lauded hero of this trend is business. While people like Bill Gates (who was a wealthy corporatist before he was a philanthropist) have wielded the mighty dollar to provide preventative care for those susceptible to the disease, the fact cannot be ignored that the cocktail of medicines and nets used for treatment were developed largely by business. These treatments are expensive, especially for the poor who need it most, but this is not without reason. The price to produce one malaria pill may be cents, but the cost to produce the first malaria pill was millions. In addition to this huge initial cost, breaking into a market thousands of miles away is difficult, and it is wrong to ignore all of the efforts involved. While making a profit on medication is morally questionable, without corporations, there would be no malaria medicine.

Throwing hundreds of fish at a man does not make him a fisherman, but it does hurt everyone selling fish. To call a job a social program may seem callous, but that does not make it any less accurate. To profit off pills may raise an eyebrow, but it does not bury a child. It is only through a combination of charity and capitalism that these deep problems can be solved.

Poverty and hunger are heart breaking, and a response is obligatory. But grief and overwhelming concern is better channeled into thought, not just dollars. Harvard law professor David Kennedy writes, “Humanitarianism tempts us to hubris, to an idolatry about our intentions and routines, to the conviction that we know more than we do about what justice can be.” The biggest barrier to effective aid is our own ignorance. As Rwandan President Paul Kagame puts it, Westerners should “have a heart for the poor. But they also need to have a mind for the poor.”