On June 24th of last year, “BRITISH STUN WORLD” was written across the top of the New York Times. The Wall Street Journal, for once, ran a quite similar headline: “UK Exit Delivers Shock”. “Brexit,” as the UK’s exit from the European Union became known, was indeed a shock. Worldwide stock markets tanked, the UK’s Prime Minister David Cameron resigned, reports of hate crimes spiked, and the value of the pound dropped to record lows. The result of the 2016 European Union Membership Referendum, however, should perhaps not have come as such a surprise; “Brexit” was by no means the first claim to additional sovereignty from within the United Kingdom, and it is only one of many to have been successful.

Over the course of its modern history, the United Kingdom has been plagued by debates surrounding the distribution and concentration of political sovereignty. As a unitary state formed by four culturally distinct nations, as a former imperialist superpower, and as a member of a powerful supranational organization, the UK is predisposed towards sovereignty disputes. Most recently these disputes have manifested themselves in campaigns for Scotland’s independence in the 2014 Scottish Referendum and in campaigns for the UK’s exit from the European Union in the 2016 European Union Membership Referendum, but these claims to greater sovereignty are by no means new or unfamiliar. In the 1880s, the United Kingdom’s Prime Minister, William Gladstone, first advocated “home rule” — a concept closely related to devolution — for the nations of the United Kingdom. At the time, his notions seemed ridiculous. The bulk of the UK’s parliamentarians held a strong belief in the necessity of union, and the concept of “home rule” conflicted with the mandate of parliamentary sovereignty which dictates that the UK Parliament has supreme and unlimited power over all political bodies within the country. Regardless of the UK Parliament’s views, talk of “home rule” and independence steadily became ubiquitous, and in early December of 1922, Ireland became independent from the United Kingdom. It was only two days later that Northern Ireland petitioned to be readmitted to the UK, but the damage to the organizational structure of the UK was irreparable. Irish independence and the idea of “home rule” set a precedent for autonomist and secessionist movements. It is this precedent, in addition to ideas of rights to self-determination, which is used to support nationalists in Northern Ireland, Wales, Scotland, England, and throughout the British Isles.

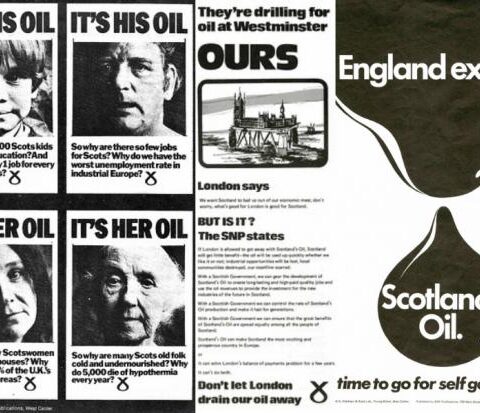

The vast majority of sovereignty-seeking movements in the United Kingdom are founded upon claims of political marginalization. In Northern Ireland, for instance, primarily Catholic Irish nationalists have historically felt ignored alongside the larger–though shrinking–Protestant community. Scots, largely alienated by Thatcherite conservatism and austerity measures, are consistently further to the left on the political spectrum than the English. As merely 8.3 percent of the United Kingdom’s population, however, the Scottish often feel overlooked in the UK Parliament—left-leaning toddlers forever pitted against the conservative giant that is England.

The English, too, are increasingly frustrated by the political deficit which has been termed the “West Lothian Question.” England, as the only constituent nation without a devolved national parliament, is usually unable to vote on legislation affecting only Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland while these other regions are actively involved in voting upon legislation impacting only England. The populace of Wales and Northern Ireland also feel frustrated by the uneven devolution of powers among states. Scotland has garnered far more devolved power for itself, while the two smaller regions have gained only minor powers from the UK Parliament. In addition, Wales and Northern Ireland feel that their combined 58 seats in the UK Parliament, challenged by 533 English parliament members (MP) and 59 Scottish MPs, make their political efforts subject to the whims of England and Scotland. First Minister of Wales Carwyn Jones went so far as to call Wales and Northern Ireland “mice sleeping next an elephant”. Even several smaller regions, particularly Cornwall, have small—but vocal—sovereignty-seeking autonomist movements. By becoming independent, or by achieving greater levels of devolution, each of these regions gain greater control over the policies enacted within their borders. It seems only natural that MPs would advocate for greater control over their regions while hoarding control over the rest of the state. The political frustrations of these nations, too, are entirely valid; political marginalization and the lack of regional equality within the United Kingdom is understandably troublesome.

Unbound by a federal constitution, the UK Parliament has the power to endow political power and authority to subnational states whenever and however it chooses. Consequently, nationalist movements regularly threaten independence and receive greater devolution from the UK Parliament as appeasement. In fact, it is for this reason that Scotland — a state which could feasibly succeed independently — has gained far more devolved powers than other less stable regions. Three days before the 2014 Scottish Referendum, every mainline UK political party offered Scotland greater devolution in a last-minute attempt to persuade Scots to vote for the unionist campaign. It is this move that likely swung the vote, keeping the 1707 Treaty of Union between England and Scotland intact.

“Brexit” began as David Cameron’s threat to the European Union, a chance to assert the United Kingdom’s sovereignty and its role as a European leader while simultaneously pacifying the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) and rapidly-defecting conservative Eurosceptics. A few conservative UK parliament members and the entirety of the UKIP, however, vocalized their frustrations with their lack of power in the European Union Parliament, in which the United Kingdom holds 73 seats — a mere 9.7 percent of the entire parliament. With so few seats, the UK plays only the role of a reluctant coalition member, rather than as a powerful European leader. Knowing that the populace of the United Kingdom is accustomed to solving problems of perceived political marginalization with calls for additional sovereignty, perhaps the world ought to have expected a British exit from the European Union — or at least a close campaign. More importantly, the United Kingdom Parliament cannot expect to maintain their union without quickly furthering devolution, establishing a more rigid organizational structure, and evening the distribution of sovereignty among each of its nations. If the UK Parliament fails to take these actions, it becomes increasingly likely that Scotland, frustrated by the loss of membership within the European Union due to widespread English Euroscepticism, will once again move to secede from the United Kingdom. This time, at least, politicians and news-media might realize that the British way of solving problems is often via threats of secession, and that political marginalization can be endlessly motivating to a disenfranchised and frustrated populous.