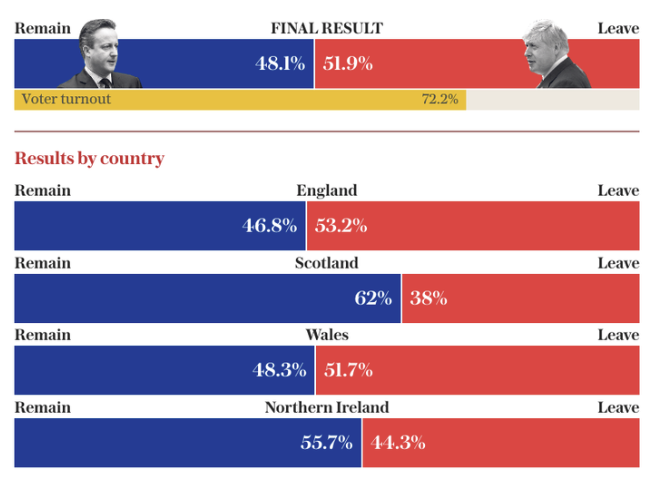

Shocking the world, the United Kingdom (UK) voted via referendum 51.9% to 48.1% to leave the European Union (EU) and remove themselves from its shared economic, political, and cultural relationship. Following this EU referendum, the UK saw their currency, the Pound, drop to its lowest value since 1985, and many have raised concerns of the economic consequences of the referendum. Though much attention has centered on the UK’s economic uncertainty following the referendum, another important uncertainty has arisen: independence movements and political dynamics in Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Gibraltar. The EU referendum has rekindled independence movements in a number of the UK’s autonomous regions, which might lead to an eventual fragmentation of the country. Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Gibraltar have a historically sturdy relationship with the EU, and they might just do anything they can to keep it.

Looking at the results from the EU referendum, many urban epicenters, such as London and Manchester, voted to remain in the EU. However, much of the surrounding rural areas across the UK voted to leave. At the nation level, Scotland and Northern Ireland voted strongly to keep their place in the European single market. Conversely, England and Wales voted marginally to leave the EU. Lastly, Gibraltar, a contested UK overseas territory, voted unwaveringly to remain. These spatially-divided results set the stage for the stirring of independence movements in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Will Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Gibraltar Secede?

During the Scottish Parliament’s first meeting since Brexit, the Scottish National Party (SNP), led by First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, immediately brought up the idea of a second independence referendum so that the nation could remain in the EU. In her speech, Sturgeon exclaimed, “If we were to be removed from the EU, it would be against the will of our people. This would be democratically unacceptable”. The Scottish Conservative Party did not support independence, as indicated by party leader Ruth Davidson in her speech. Davidson called the SNP’s push for independence “utterly unjustified”. However, the SNP, with the combined effort of minor pro-independence parties in Parliament, hold the necessary votes to introduce a second independence referendum.

The SNP has already shown their firm commitment to remaining in the EU. Sturgeon stressed that status as an EU member state was Scotland’s first goal, and independence was next in line; staying in the EU is Scotland’s first priority. While the largest party in Parliament has already introduced the idea of another vote on Scottish independence, Sturgeon and the SNP will first focus on finding a way to keep Scotland in the EU.

Gibraltar, a lesser-known territory of the UK, has been less enthusiastic about leaving the UK than Scotland, but still wants to keep their EU membership. In Gibraltar, the vast majority of citizens voted to stay in the EU. However, surveys show that a large majority of Gibraltar also wants to stay in the UK. Gibraltar’s Chief Minister Fabian Picardo has been in close contact with Sturgeon to examine ways in which parts of the UK could remain in the EU. Adding to the frenzy, Spain’s foreign minister, Jose Manuel Garcia-Margallo, proposed the idea of Spain attaining joint sovereignty over Gibraltar. As an EU member state, Spain could take joint control over Gibraltar and offer the nation its spot back in the EU.

Similar to Scotland, Northern Ireland also has a strong bond with the EU that it intends to keep. Citizens in Northern Ireland voted similarly to those in Scotland: 55% of the country voted to remain in the EU. Following the referendum, the deputy first minister called for a vote on Northern Irish independence. Northern Ireland has also been in contact with the EU to examine possible avenues to stay in the EU while remaining in the UK. While the independence movement in Northern Ireland is less prominent than in Scotland, Northern Ireland’s now-broken bond with the EU could rekindle agitation for independence.

In regards to continued EU membership for Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Gibraltar, there is no clear precedent for parts of a country staying in the EU while the rest of country leaves, but many have pointed to the EU membership of Denmark and Greenland as a possible precedent for segments of a country staying in the EU. No country has ever left the EU, which makes Brexit entirely unprecedented. While no non-EU country has parts of their country in the EU, Denmark and Greenland have a comparable situation. In Denmark and Greenland, both EU member states, a number of territories in each country are not in the EU despite their entire country’s membership.

Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Gibraltar could push for a similar situation, in which they would gain access to the European single market while also staying in the UK. Although the Greenland/Denmark situation is the reverse of the one Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Gibraltar face (regions wanting to stay in the EU while the country wants to leave), this could be interpreted by the EU as a possible precedent for parts of the UK staying in the EU while the rest departs. However, since the UK is the first country to leave the EU, the legality of many of these propositions are opaque. It is possible for parts of the UK to stay while others leave, but the EU and the UK must approve this decision and have a legal basis for it. While these speculations show each country’s dedication to their partnership with the EU, whether they can find legal justification for these strategies to stay in the EU is still unclear.

Can Scotland and Northern Ireland Block Brexit?

A number of constitutional experts, including Sir David Edwards, have argued that Clause 29 of the 1998 Scotland Act gives the Scottish Parliament legal authority to rule on the Brexit referendum—and any UK policies that affect the nation’s relationship with the EU—independently of the UK Parliament. This act was a pivotal statute devolving federal power to the Scottish Parliament, and many argue that the act gives Scotland the ability to decide on the EU referendum. Since the act gave Scotland power over the implementation of EU law, Edwards claims that Scotland’s regional governmental power outlined in the act provides the nation with the means to have a local Scottish vote on whether to remain in or leave the EU.

It is unlikely, however, that Scotland can block Brexit and have a local vote on the referendum. During a personal meeting with Iain McIver, senior researcher for the Scottish Parliament, he argued to me that there is no constitutional or legal support for the argument that the Scotland Act gives the Scottish Parliament the ability to block the Brexit vote. The clause in the Scotland Act that Edwards and others cited was not designed for that constitutional interpretation. Even if Scotland decided to block Brexit, it is very doubtful that UK’s Parliament in Westminster would validate this approach. Additionally, it is very unlikely that Sturgeon or the Scottish Parliament will even attempt to block the referendum. Although many speculate that this clause can be used to constitutionally legitimize Scotland’s power to block the Brexit, such speculations are doubtful at best.

In a similar fashion, the 1998 “Good Friday Agreement” between the UK Parliament and Northern Ireland has raised questions as to whether the nation could block Brexit themselves. The statute in question states that Northern Ireland was given power over its place as a “partner in the EU”. However, this clause, similar to the one in the Scotland Act, lacks a constitutionally sound argument and will most likely be illicit due to the lack of elaboration of the genuine meaning of the clause in the context of Northern Ireland’s relationship with the EU. There is little evidence that this clause was meant for this interpretation. In short, arguments that Scotland or Northern Ireland could block the Brexit vote or have a local referendum by citing broadly-interpreted, minor clauses are not likely to gain much traction.

What Will They Do?

The initial reactions to the outcome of the EU referendum have focused primarily on rejoining the EU, with independence featuring secondarily. Scotland is wholeheartedly determined to stay in the EU. Gibraltar and Northern Ireland have similar positions: both countries are focused on exploring avenues to remain in the EU. After investigating the possibility for continued EU membership, the two countries will decide whether or not they want to pursue independence from the UK. However, it is clear that the leader in this push to keep UK’s relationship with the EU intact is Scotland. Sturgeon has been travelling to both Northern Ireland and Gibraltar to discuss the consequences of the referendum as well as a political path forward. The two countries are cooperating with Sturgeon to explore ways to stay in the EU.

It seems very likely that Scotland will have a second independence referendum if they are not granted EU membership. The future of Northern Ireland and Gibraltar are less clear: these countries want to stay in the EU, but are less inclined to push for independence. If Scotland under Sturgeon can lead a strong push for continued EU membership, Northern Ireland and Gibraltar could follow Scotland’s path to independence. Although the political dynamics of the three regions are still developing, only time will tell if the United Kingdom can remain unified despite such spatially-divided opinions for their status as an EU member state.