By Kalvis Golde

This article was originally published in GPR’s Fall 2017 Magazine

Meddling in elections is increasingly commonplace in the United States. From super PACs and the meteoric rise in spending on behalf of political candidates, to allegations of foreign interference in the most recent presidential race, Americans are no strangers to outside influence on the ballot box. But the pressure reaches deeper than races for federal, state, or local office, to a sphere rarely considered by the public or media: university student government elections.

Within the past five years, various non-profit organizations have embarked upon buying or otherwise influencing the election of student government officials at colleges around the country. A natural progression of the great American elections-spending arms race, the targeting of student government elections is a new component in the political strategy of building coalitions within local government and grassroots movements to supplement power in Washington, a strategy commonly employed by both major parties as well as national advocacy groups.

This trend enjoyed scant attention for years. Now students are starting to pay attention.

A Political Turning Point

The political 501(c)(3) non-profit organization holds special status in the United States tax code. Because they are restricted from directly supporting political candidates, these groups are granted tax exemptions and a large degree of autonomy in their financial operations. A small army of these politically inclined non-profit organizations dots political centers around the country, ranging from powerful think tanks like the Center for American Progress (CAP) and the Heritage Foundation to single-issue advocacy groups like Mothers Against Drunk Driving, the group that led the push for the current national drinking age of 21.

A number of these organizations have arms dedicated to younger generations or university students, such as CAP’s Generation Progress unit or the Campus Action Network of the National Organization for Women. Many of these national groups have spawned student club chapters at universities around the country, using this vast network to champion their issues to students and recruit them for the group’s efforts.

One such group is Turning Point USA, a 501(c)(3) organization founded in 2012 by rising political star Charlie Kirk in order to help students “promote the principles of freedom, free markets, and limited government.” The group boasts a student organization or other form of presence at over 1,000 schools around the United States, including the University of Georgia.

The group gained national notoriety for its Professor Watchlist, an online database of professors reported to “discriminate against conservative students and advance leftist propaganda in the classroom.” While provocative, the group certainly is not unique. Many universities boast overtly political groups such as the College Republicans and Young Democrats, and there are a host of left-leaning 501(c)(3) organizations famous for their activism on college campuses, such as Move On and — likely familiar to UGA students — the group Athens For Everyone.

The difference between Turning Point USA and its counterparts on both the ideological right and left is strictly one of strategy. As of now, Turning Point and its partner, the Campus Leadership Project, are the only groups publicly known to target student government elections to advance their efforts.

On The Offensive

“It might seem like kind of a silly thing to try to take over student government associations,” Turning Point founder Charlie Kirk conceded during a 2015 speech to a right-wing political group called the David Horowitz Freedom Center (DHFC). Yet in reality the strategy is far from naive.

The voice of the student body at most schools, student government often wields significant influence on university administration as well as state and local policy. Occasionally their budgets sit in the range of millions of student fee dollars. In many states, the ranks of the political elite swell with veterans of student government, especially from flagship institutions. Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, Hillary Clinton, and Richard Nixon all trace their roots to bids for the student body presidency at their respective colleges.

There is real power to be found in university student government, and Kirk believes he has found a way in. “The only vulnerability there is, the only little opening,” Kirk explained to the DHFC, “is student-government-association races and elections, and we’re investing a lot of time and energy and money in it.”

So what does this “time and energy and money” look like in practice? The evidence is murky and incomplete, due largely to the national organization’s tight-lipped policy. But various university newspapers around the country have uncovered bits and pieces.

Occasionally it constitutes direct monetary aid. Two years ago, the president of the University of Maryland College Republicans sent a message through his group’s listserv advertising an enticing opportunity: “Anyone who wants to run for SGA president, Turning Point is offering to pay thousands of dollars (literally) to your campaign to help get a conservative into the position.” This past year at Ohio State University, leaked text messages between a Turning Point representative and student candidates disclosed nearly $6000 in offered financial support.

While that amount of money may seem inconsequential when compared to the nearly $2.4 billion spent on the 2016 presidential race alone, it can make a big difference at the collegiate level. Most universities set a spending cap for student government candidates at a few thousand dollars, so Turning Point assistance can quite literally double or triple a campaign budget. “You would be amazed,” Kirk gushed to the DHFC, hinting at this leverage. “You spend $5,000 on a race, you can win. You could retake a whole college or university.”

Other times, this aid takes the form of non-monetary support. Turning Point reportedly employs teams who “wake up every single day, just as if you’re running a congressional or mayoral race or senate race, trying to develop messaging, fliers, banners, Twitter profiles” for candidates, according to Kirk. Occasionally, bits of this aid go public. At the University of Maryland, the student newspaper “The Diamondback” reported that this past year’s Unity Party received undisclosed logo designs from a Turning Point designer.

Some candidates have even been offered physical manpower. Leaked messages between a Turning Point representative and an Ohio State student discussed sending “a bunch of people with tablets making people vote and everything” on voting day, at no cost to the candidate — “they’ll pay those people too.”

In The Dark

Many of the mammoth private groups that spend on national elections, from various cheerily named super PACs to the Koch brothers, are widely known. Yet this notoriety usually comes despite their best efforts.

Groups that attempt to sway votes with dollars generally prefer to operate in secret, and this is certainly true for Turning Point. Their effort to influence student body elections is a “rather undercover, underground operation,” founder Charlie Kirk explained.

This choice is for good reason. At schools where their efforts to sway elections are made public, the Turning-Point-backed ticket or candidate tends to lose. The entire Unity Party at the University of Maryland withdrew from the race after the source of those logo designs was revealed. At Ohio State, candidates with allegations of Turning Point ties dropped out a few days before the election following a student media firestorm. Last year’s One Oregon ticket at the University of Oregon lost what promised to be a successful elections bid after evidence of Turning Point aid surfaced to the student body. (There is no evidence that a candidate backed by Turning Point has successfully completed a bid for student government at the University of Georgia.)

Yet in many cases, especially when undiscovered, the operation seems to achieve rather marked success.

When a victorious presidential candidate at the University of Colorado was kicked out after the discovery of undisclosed Turning Point funding, a prominent conservative lawyer filed a flurry of legal action which resulted in a decision by the U.C. chancellor to reinstate the candidate as the victor. The attorney refused to release the source of his funding.

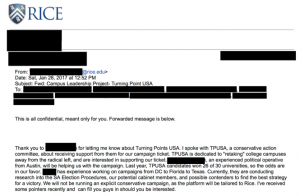

This past January, an email leaked from a candidate at Rice University who sought assistance from the Campus Leadership Project, a Turning Point partner, in their school’s elections. The leak exposed a sobering statistic: “Last year, [Turning Point USA] candidates won 26 of 30 universities, so the odds are in our favor.”

A Broader Movement

The sudden rise in outside spending on student government races did not occur in a vacuum. The United States has been grappling with seismic shifts in the elections-funding landscape for nearly a decade.

In 2010 the U.S. Supreme Court issued a landmark opinion in the case Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission that blew the door open for unlimited elections spending by corporations. The ruling followed a controversial concept in jurisprudence: just as human beings are protected by the Constitution from federal restrictions on their freedom of political speech (dollar-speech included), so are corporations.

Super PACs, once a fringe element of American elections, owe their modern prominence almost entirely to the Citizens United decision. But in the world of nonprofits, that ruling applies solely to 501(c)(4) organizations such as PACs, which are not barred from spending on behalf of political candidates and thus are not granted the same tax-exempt status as 501(c)(3) groups.

Turning Point USA is classified as a 501(c)(3) organization. While the rapid expansion of its targeting of student government elections cannot be traced to the Supreme Court as directly as the Political Action Committee, the very concept of Turning Point’s strategy stems from the consequences of that case.

Its classification as a 501(c)(3) should, in theory, prevent Turning Point from contributing financially to candidates for student government. But there is a notable caveat. IRS restrictions on 501(c)(3) contributions to political candidates concern only those running for public office. As of now, the legal world does not classify student government representatives as public officials, an exception cited in leaked messages from a Turning Point representative to a student at Ohio State: “[Our support is] totally legal and everything, because it’s a student government campaign, it’s not like Congress or the president.”

With all the controversy surrounding the onslaught of moneyed interests in university elections, however, it’s possible that the legal definitions here may change in the future — especially for student government officials at public, state-funded universities.

The political landscape at universities is facing drastic change as well, as controversial issues once again encroach on campuses around the country. The police shooting of Michael Brown in St. Louis prompted protests at the University of Missouri which led to the ouster of leading school officials and an enrollment crisis at Mizzou that lingers today. The alt-right movement led by Richard Spencer in Charlottesville, VA, and the resulting death of a counter-protester have rocked the University of Virginia to its core.

As Mr. Spencer and other alt-right speakers amp up their national college tours, protests — and student arrests – have been sparked around the country in response. And the federal government has now waded into the fray, with Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ recent promise to back lawsuits against schools that have banned Mr. Spencer and other speakers from appearing on their campuses.

Spending on student government elections and controversial university speech are distinct yet pivotal factors in the undeniable, forceful return of politics to college campuses around the country. The best thing students can do in response to the turmoil is to pay attention. A watchful eye, an open mind, and concerned participation in university life can go a long way in diffusing the political tension pressuring students at our nation’s colleges. Now more than ever, it is critical that students affirm their commitment to their schools, and to each other.