Last summer, following years of hostilities, island building, and close encounters on the South China Sea, The Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague ruled in favor of the Philippines and stated that China’s claim to much of the sea had no basis in history or law. China, sticking to its “9 dash line” territorial claim that encompasses much of the South China Sea, took exception to the ruling, claiming that the decision was “shameless,” “illegal,” and stated that depriving China of the South China Sea in its entirety would leave it without an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in which to operate. Many member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), an intergovernmental organization consisting of ten states located in Southeast Asia, with claims in the sea were pleased by the ruling. However, many were also simultaneously weary of trying to enforce it due to China’s previous refusal to abide by the verdict. “[Making China abide by the ruling] will take time,” said one official in the Philippine Navy, “not in the next five or ten years.”

For ASEAN, this was an important victory, at least on paper, because its members Vietnam, Malaysia, Philippines, and Brunei all have territorial claims in the sea which overlap with China’s “9 dash line.” Indonesia also has territory in the South China Sea but has not officially claimed to have an EEZ in the area. Because this ruling validated the claims and concerns of many ASEAN members, it was expected that the South China Sea issue would be one issue in which the organization, known for its relative fragility, could present somewhat of a united front against an increasingly assertive China. Some, such as Philippine Foreign Secretary Perfecto Yasay Jr., lauded the ruling as a “milestone” and a “clean sweep for the Philippines,” indicating that the verdict, while non-binding, was nonetheless an unexpected surprise.

Unfortunately for ASEAN, the ruling has not had the effect it expected on its members. When the foreign ministers of each of the ASEAN member states gathered to issue a statement on the South China Sea, one which urged China to respect and abide by international law, the representative from Cambodia rejected the proposed wording of the statement, the first time ASEAN had been deadlocked about issuing a statement since 2012 (that deadlock was also caused by Cambodia rejecting a South China Sea resolution). Unlike intergovernmental organizations such as the European Union (EU), ASEAN is a diverse and somewhat fractured organization which has as much power and leverage as its members will give it. Cambodia, though geographically located in Southeast Asia with interests in ASEAN, is China’s closest ally in the region and, in return for China becoming the largest foreign investor in Cambodia, supports China’s positions on issues like the South China Sea. While the Cambodia issue has been around for years, the prospects for a “unified front” against China by ASEAN have been weakened further by the election of Rodrigo Duterte as President of the Philippines. Duterte claims to have put the South China Sea issue “on the back burner” in order to improve relations with China, and his country is now chair of ASEAN. While it is not expected that Duterte will work to spread China’s influence with ASEAN, there is little chance he will allow the organization to work against China since it may hurt his country.

While the South China Sea dispute is more of a recent issue, the history of Southeast Asia’s and ASEAN’s relationship with China has been complex and at times somewhat hostile. Some of this can be attributed to widely varying attitudes on China’s political ideology within Southeast Asia. For example, Indonesia under former president Suharto summarily executed hundreds of thousands of members and sympathizers of the Communist Party of Indonesia in 1965 with the help of western countries while Vietnam and Laos are still operating as single-party “socialist” states like China. Despite having ideological allies on paper, China was still an enemy to Vietnam, Laos, and formerly Cambodia, since all of them sided with the Soviet Union in lieu of an unstable China following the Sino-Soviet Split in the 1960s. For Cambodia, the split became especially pronounced when China backed the genocidal Khmer Rouge government before and after it was ousted from power by Soviet-backed Vietnam in 1979. However, due to the fact that many of its member states were either part of the Non-Aligned Movement or had informal alliances with the west, ASEAN helped prevent recognition of the new Soviet-backed government in Cambodia, working closely with China to overthrow it (to no avail) and spiting its members Laos and Vietnam in the process. This is important to note because it is just one of many episodes where the fragility of ASEAN was exposed and shows how, no matter what the issue is, obtaining unanimous agreement on foreign policy with China in the organization has almost always been difficult.

Aside from political diversity, ethnic diversity in ASEAN countries has also been something which has, at times, made relations with China difficult. This is not only because each member state is diverse in its own right but also because, out of ASEAN’s combined population of 625 million, at least 25 million are ethnic Chinese or of Chinese ancestry. This number rises if those claiming partial descent are included. Part of this number can most certainly been attributed to Chinese immigration within the past century, but many ethnic Chinese living in ASEAN countries today are descendants of merchants, traders, and officials who moved to Southeast Asia, raised families, and plied their trades between the 15th and the 19th centuries, forming a community now known as the Peranakans. Although there are a sizeable number of Chinese in ASEAN countries, those countries have not always been the most tolerant towards them. Malaysia expelled Singapore from the country due to its mostly Chinese population, Indonesia allowed Chinese Indonesians to be targeted and killed in riots due to the disproportionate amount of wealth they owned, and Vietnam pushed out hundreds of thousands of ethnic Chinese during its conflict with China in the late 1970s.

This population of ethnic Chinese is most certainly beneficial for ASEAN, with ethnic Chinese contributing anywhere from 50 percent to 70 percent of the GDPs of states such as Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines despite encompassing only about 3 percent to 4 percent of the populations of the countries. The worry for both non-Chinese and Chinese in ASEAN is that China would exploit the strife occurring between different ethnic groups and galvanize Chinese groups which may still feel attached to their homeland. In fact, as former Singaporean Prime Minister and ethnic Chinese Lee Kuan Yew pointed out in the book Lee Kuan Yew:Hard Truths to Keep Singapore Going, ASEAN had to confront China and communist parties within its member states about transmitting broadcasts which directly appealed to ethnic Chinese in an attempt to deepen communal strife for China’s benefit. Despite discrimination against them, however, China has largely failed to mobilize ethnic Chinese populations due to the simple fact that many families have resided in Southeast Asia long enough to where they no longer feel much attachment to their ancestral homeland. According to Lee, the idea that Chinese Peranakans like him have a desire to return to the “bosom of their motherland is a delusion.” In fact, despite his home country being made up largely of ethnic Chinese, he indicated that he chose to make English the main state language of Singapore because “no Singapore parent…wants his son to have a schooling that does not give him a command of English.” Lee’s comments reflect not only the attitude of many ethnic Chinese in ASEAN countries but also the majority populations. Despite its geographical proximity to China and a growing number of countries expanding Chinese language instruction, English remains the language of choice for both business and political elites in ASEAN countries, ethnic Chinese or not.

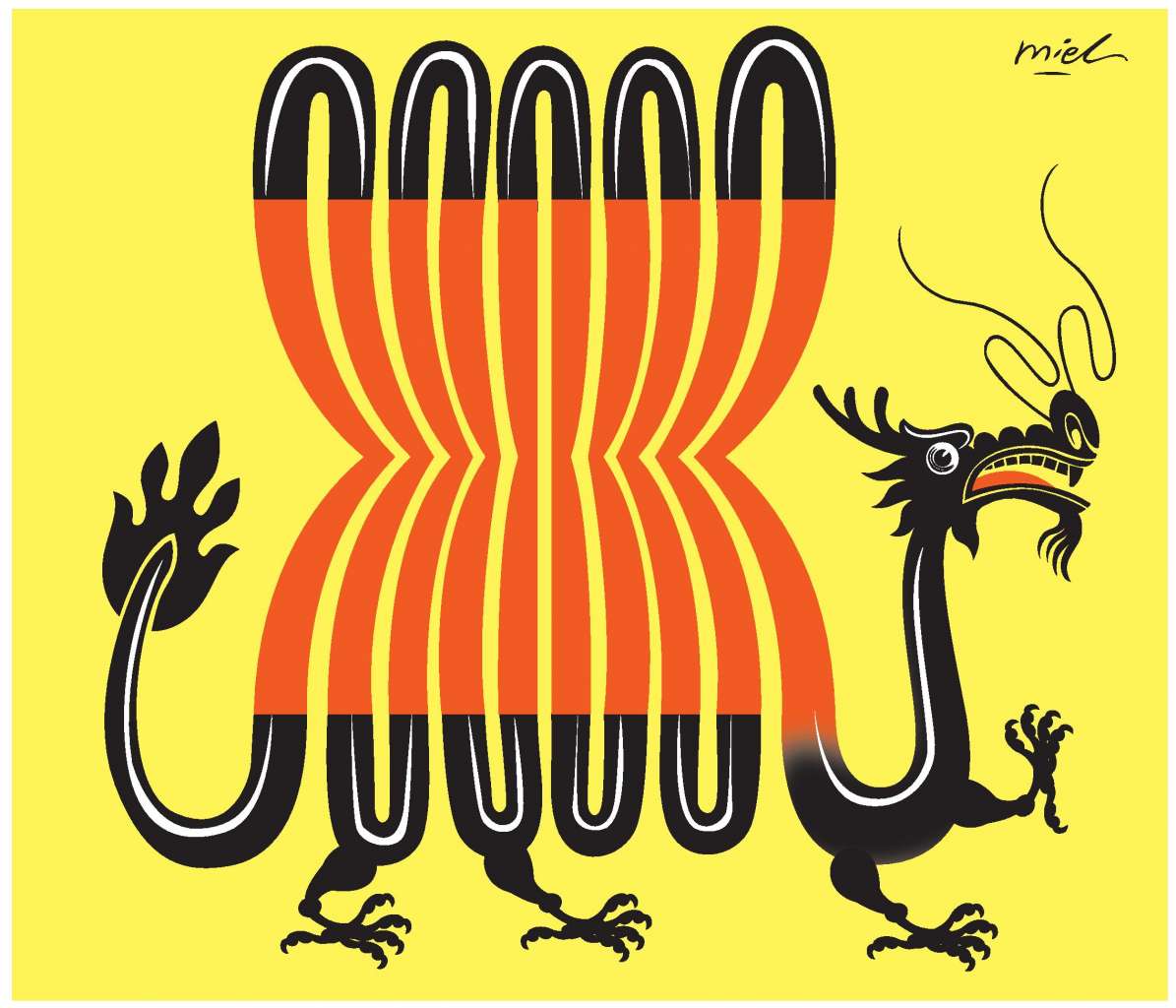

Up to this point, whatever inroads China has made into ASEAN have been temporary, based on appeals to ethnic Chinese, and focused on individual countries instead of the organization as a whole. Based on the South China Sea dispute, where China prefers bilateral negotiations with affected countries instead of ASEAN as a whole, it seems that the most practical way for China to keeps its existing influence in the region would be to divide ASEAN and therefore weaken its bargaining power. This is evidenced by the fact that Cambodia and now the Philippines are cozying up to China and inhibiting the formation of any “unified front.”

But could China actually be limiting itself by dividing ASEAN and holding so firmly to its expansive territorial claims? While there is no doubt that weakening ASEAN could prevent it from counteracting China in the South China Sea and allow China to solidify its grip on the islands within the sea, such an action may go against the economic interests of ASEAN and China. Since the 1970s, both China and ASEAN have been mutually beneficial economic partners, with ASEAN continuing to engage with China after the western world shunned it following the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre and China in return proposing a free trade agreement with ASEAN, the first state to do so. Even today, despite their geopolitical issues, China is investing heavily in not only new allies such as the Philippines but also Malaysia and Indonesia, two countries where economic growth has been strong and wages remain low. However, many argue that China, by sticking so firmly to its territorial claims, is shooting itself in the foot economically and opening the door for other countries that are willing to engage with ASEAN instead of just its individual member states. It remains to been seen if other individual ASEAN members will follow Cambodia and the Philippines in pivoting to China, perhaps creating a new unified front which actually supports China, but for now there is little doubt that the current Chinese position on the South China Sea only serves to hurt both China and ASEAN.