By Kalvis Golde

The Supreme Court is aging. By year’s end, three of the nine sitting justices – Anthony Kennedy, Antonin Scalia, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg – will be at least 80 years old. The next president will almost certainly have the opportunity to select the replacement for one of these high judges, which could shift the ideological leaning of the court toward the future president’s politics. But losing one of the court’s three octogenarians in particular would constitute a major change in the dynamics of the court’s decision-making.

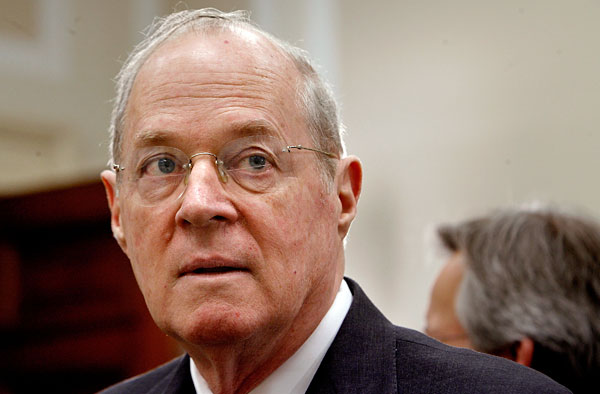

Justice Kennedy is the court’s resident swing voter. Not beholden to the liberal or conservative leaning justices, he casts the deciding vote in the vast majority of close opinions. His influence is commanding: some people even dub our Supreme Court the “Kennedy Court” as opposed to its official moniker, the “Roberts Court”, after Chief Justice John Roberts. In nearly 30 years on the court, Kennedy has elicited celebration and anger from both parties, having voted to strike down or uphold laws originally proposed by each. If he retires, the next president will face a momentous appointment opportunity.

A deeper analysis of recent Supreme Court terms provides a clear picture. Since 2007, Justice Kennedy has been in the majority of 80 percent of five-to-four decisions. That is impressive, since the next highest percentage notched is 62 percent by Clarence Thomas, and most of the other justices hover between 30 and 55 percent. This past term alone, Kennedy sat in the majority on 14 of the 19 five-to-four opinions, and 13 of those 14 were completely split between left and right leaning justices. A lot of highly publicized cases, like those on the Affordable Care Act and same-sex marriage, were decided last term; Kennedy decided two-thirds of them on his own. And this coming term promises to be similarly contentious.

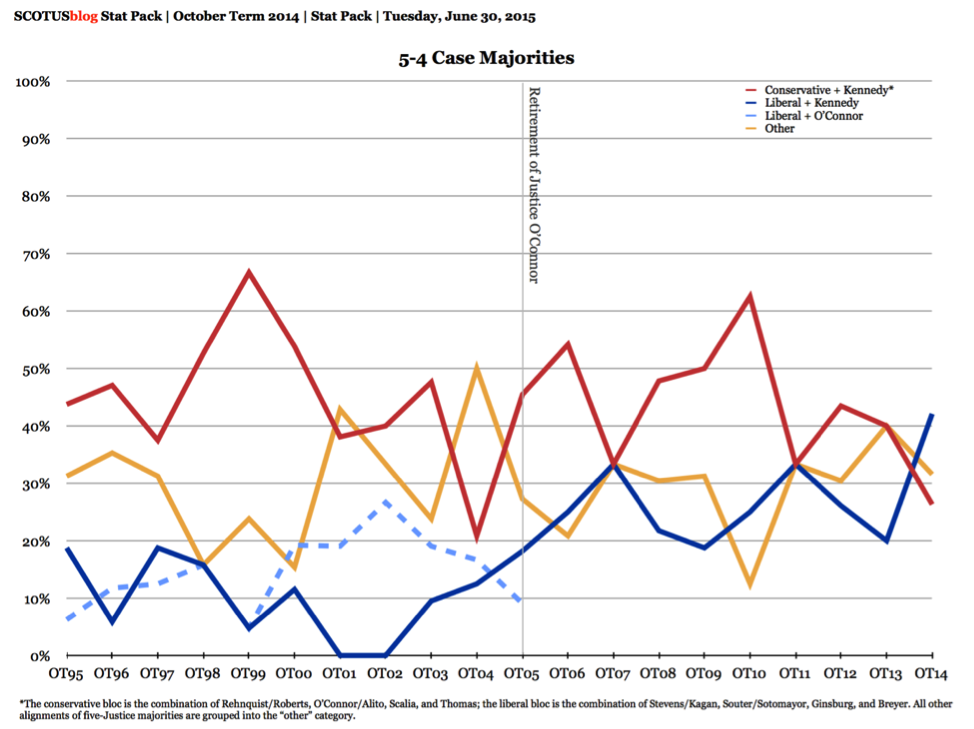

There is an important caveat. A deeper look at the data suggests Kennedy is less impartial than we may expect from a swing voter. In the graph below, the red line illustrates the percentage of 5-4 cases that were decided by the conservative leaning justices plus justice Kennedy; the dark blue line shows the same for Kennedy deciding with the liberal leaning justices. One glance at the picture is telling: with the exception of this past term, never in Kennedy’s entire career has he decided more 5-4 cases on the liberal side than on the conservative side. And that is part of what made this last Supreme Court term so monumental.

Two of the most contentious recent decisions were decided by Justice Kennedy.

First in Jan. 2010, Kennedy sided with the conservative justices in declaring limits on campaign finance an unconstitutional restriction on free speech in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. The decision gave super PACs and donors free rein to spend unlimited amounts of money on behalf of political candidates.

Then in June 2015, Kennedy joined the liberal justices’ bloc in striking down state bans on same-sex marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges. Arguably the most followed Supreme Court case of the 21st century, Obergefell formally ended the debate over marriage equality.

The true weight of Justice Kennedy’s swing vote is illustrated by these two important cases whose decisions ultimately fall on very different sides of the political spectrum. But Kennedy did more than just cast the key vote in both of these cases: he also wrote the majority opinion in both. The phrases that will be forever associated with these moments, the passages that will be quoted in history textbooks, are his words. One could argue that Kennedy’s legacy is cemented in these two cases alone. When one considers the countless other close cases he’s decided, many of them equally notable, his influence becomes undeniable.

Justice Kennedy has defined an era for the Supreme Court, but that era is coming to a close. Kennedy is 79 years old, and Supreme Court justices retire at an average age of 78.7. The mere fact that a third of the court is past this age is significant enough. The reality that the next president will likely bear the responsibility of replacing Kennedy specifically makes the situation all the more momentous.

This is arguably the biggest issue at hand in the 2016 election. All of the hot issues on the campaign trail – ISIS, climate change, and immigration, to name a few – may stand before the Supreme Court one day. One would be remiss to think that one party holds all the right answers to these problems. After all, the United States of America is built on the tension between conservative and liberal solutions. This magnifies Kennedy’s importance: when all Americans experience victory and loss by his decisions on the court, we are saved from complacency and incited to fight for our beliefs. Today’s congressional gridlock makes that jolt even more crucial.

In that way, Kennedy breathes life not only into an otherwise conservative Supreme Court but to our nation as a whole. We should hope that whoever we elect as our next president appoints a similarly moderate swing-vote to replace Kennedy. If Kennedy’s replacement is a staunchly consistent ideologue, we could enter an era in which the Supreme Court is not a dynamic, living body at all, but rather an entity that hands out uniform victories for one party and losses for the other. That would be a shame.