By: Andrew Peoples

In the wake of the Occupy movement and Arab Spring, Time magazine named “The Protester” its 2011 person of the year. It’s been three years, and the Arab Spring has given way to a disheartening winter and the Occupy movement has died off. However, three disparate countries, Venezuela, Thailand, and Ukraine, have broken out into unrest that has threatened the stability of governments in Venezuela and Thailand and has already toppled the leader of Ukraine. It’s only two months into 2014, and it looks like this may be another year of the protester.

Ukraine has been the most visible scene of protests. Thousands of people spilled out into the streets last November protesting President Viktor Yanukovych’s decision to reject a far-reaching trade pact with the European Union in favor of stronger ties with Russia. During the past three months of protests in Kiev’s Independence Square, the Ukrainian government passed severe anti-protest laws and ordered police attacks on student protesters. Contrary the government’s intentions, these measures have only caused the protests to intensify and spread to other cities across Ukraine.

The protests began peacefully and with a festive, even optimistic air, but they have seen sporadic episodes of violence since late January, and they devolved into an all-out battle just before the ouster of President Yanukovych on Feb. 22. The first protester deaths occurred in January when police shot two people, and the body of an abducted activist was found in the woods a few days after he went missing. The violence has escalated tremendously in the past week or so, with at least 77 people killed and hundreds more injured from Feb. 19-20, as police snipers fired into crowds of protesters armed only with makeshift shields. Protesters were provoked when the speaker of the parliament refused to allow discussion of a proposal to reduce the president’s powers, inciting many of the 50,000 people in Independence Square to march on the parliament.

Parliament took notice. President Yanukovych had already offered some concessions in talks with the foreign ministers of France, Germany, and Poland. He agreed to hold early elections in December and return to the 2004 constitution, which would reduce his own office’s power. But the Ukrainian parliament, perhaps appalled by the police’s brutality in the streets, was not satisfied and voted to remove him from office. An interim Ukrainian minister has now announced the existence of a warrant for the former president’s arrest for “mass murder.” Former President Yanukovych has fled Kiev and as of Feb. 26, his whereabouts have not been confirmed.

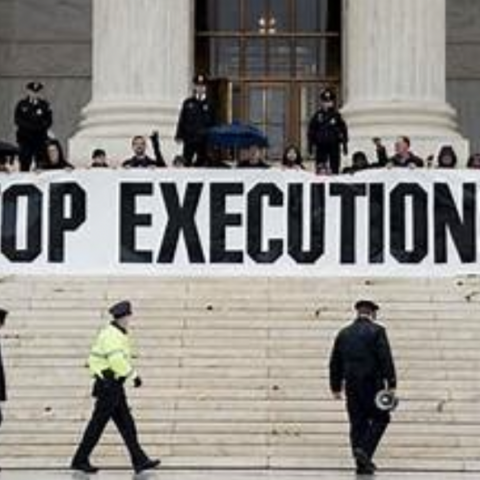

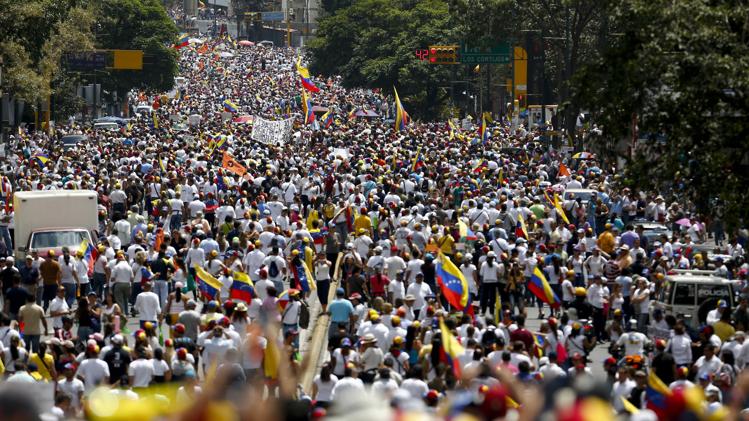

Protests of a similar scale to those in Ukraine, but with much more uncertain results, are currently taking place in Venezuela. A combination of a 56 percent inflation rate, a high crime rate, major goods shortages, and demands for the protection of free speech have brought thousands of protesters into the streets of Caracas. Nicolas Maduro, the Venezuelan President and handpicked successor to Hugo Chavez, has vowed to take a hard line against the protesters. Comparing them to fascists, he implied that imprisoning the protesters, whose ranks include a large number of students as well as some long-time opposition activists, is not repression but rather “justice.” The nominal leader of the protests, Harvard-educated economist Leopoldo Lopez, has already been arrested and taken into custody.

Major goods shortages have left store shelves bare in Venezuela for months. The government has accused distributors of orchestrating the shortages to foment unrest, but critics have long accused Venezuela’s currency controls and nationalization of private companies of leading to long-term economic ruin. The severity of these issues is threatening President Maduro and his attempts to continue Chavez’s socialist policies, but his regime is stronger than Yanukovych’s was in Ukraine. Maduro still enjoys the support of the Venezuelan lower class, which Chavez won over with his economic policies, and the military still stands behind him as well. Maduro lacks the charisma of Chavez, and these factions may yet turn on him, but it is far too early to write his government’s epitaph.

Finally, anti-government protests in Thailand have prompted international travel warnings and gridlocked the capital city of Bangkok. These protests were incited by an amnesty bill that would allow Thaksin Shinawatra, who is a former Prime Minister ousted in a 2006 coup and convicted of corruption, to return without serving jail time. Yingluck Shinawatra, the deposed leader’s sister, is currently the Prime Minister of Thailand. The bill did not pass the Thai senate, but protests continued as new demands emerged.

The protests began in November and continue today, already lasting as long as the Ukrainian protests. Most of the protesters are urban, middle-class voters, and supporters of Thailand’s Democratic Party, the main opposition to the Shinawatras’ dominant Pheu Thai party. Many among the protesters are monarchists who, tired of losing elections to the more popular Pheu Thai party, are calling for the creation of an unelected “people’s council” to replace the parliament. At least 20 people have died from violence related to the turmoil. Counter protests by “red shirts,” supporters of the Pheu Thai party, have been rare, but many have promised to take to the streets if the military ousts the government, as the protesters are demanding. Even if the protesters succeed, the conflict in Thailand has only just begun.

Different issues characterize the conflicts in Thailand, Venezuela, and the Ukraine, but all three mass movements claim that their nation’s leader is mismanaging their country, and all three demand their leader’s removal. Not unlike those of the Arab Spring, these protests aim to punish heads of state perceived as unaccountable to the people through massive grassroots mobilization. Regardless of how each movement plays out, clearly protesters are already having another active year.