By: Tia Ayele

As one of the most controversial issues in the discourse of public health and human rights, female genital mutilation (FGM) persists in much of the developing world. Practiced in Latin America, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, it is estimated that over 3 million girls undergo FGM each year. Although FGM is perceived as a provincial cultural practice by most of the Western world, FGM has irrefutable social merits for communities that value female chastity.

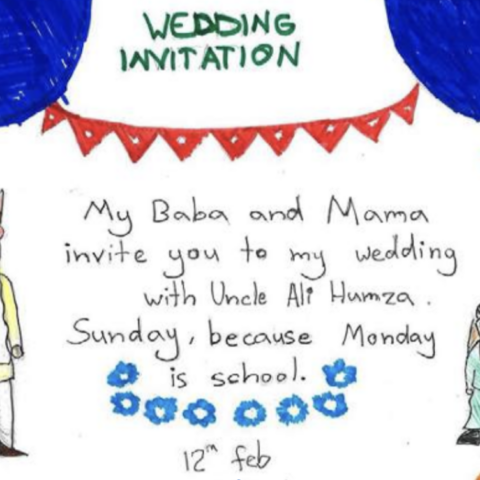

For its practitioners, FGM is an act tantamount to a female rite of passage, a necessary tradition that denotes the entrance into womanhood. Once a girl is “cut,” she has achieved the venerable ascension from her childhood and is consequently ready for marriage. Because FGM is a normalized practice to affirm womanhood and to reinforce the subscribed gender roles of a said community, choosing not to participate in FGM would be emblematic of social delinquency. An “uncut” woman would then be perceived as a social outcast, a woman who is devoid of purity and who in turn has no functional value in society.

Furthermore, the social merits of FGM can be better understood when recognizing the role of marriage in these societies. In communities such as these, marriage is one of the few ways in which women can obtain socioeconomic leverage. Through marriage, a woman is able to provide for her family and enhance her socioeconomic status. FGM is necessary for a woman to participate in the sanction of marriage and thus a requisite for a woman to have a socioeconomic advantage. Because FGM is perceived to ensure fidelity and sexual chastity, the “uncut” women, regarded as sexual deviants, are not chosen for marriage and hence, lose their means of social empowerment.

However, to identify FGM as an exclusively socially empowering practice and to infer that victims of FGM are left unscathed is a completely false assertion.

FGM is both destructive and advantageous; it is undoubtedly destructive in terms of its implications for women’s health and its perpetuation of patriarchal ideals that equate a woman’s worth with her virtue. In the same regard, the practice is also advantageous in terms of its significance in maintaining social cohesion in societies that value female chastity.

To understand the cultural value of FGM is critical to finding viable solutions for it. The most agreed upon remedy prescribed by the international community has been to ban FGM altogether. Yet, the problem with a ban is that it imputes FGM to primitiveness, and implies that cultures that facilitate FGM are “bad” or

inferior to western ideals that reject the premise of its practice.

In recognizing the cultural value of FGM, safe alternatives can be uncovered. An alternative rite of passage created in Kenya known as Ntanira na Mugambo or “Circumcision through Words,” has become prevalent in 13 different villages throughout the country. The weeklong program includes counseling sessions and celebratory events hosted by the community that mark the entry into womanhood. These type of solutions have the potential of achieving cross-cultural legitimacy and are more promising in stopping FGM than an outright ban.

In closing, it is necessary that we imbibe FGM as a legitimate cultural practice and find solutions for it with an open mind. Alternatives, such as the one that has proved successful in Kenya, can reconcile the destructive practice of “cutting” while mutually acknowledging the cultural significance embedded in the practice. By abandoning a western-centered view on FGM, we can see the advent of a new kind of cultural legitimacy. The inclusion of new perspectives and cultural ideals can provide us with viable solutions for FGM and other human rights woes of the developing world.