By: Emily Fountain

“To be forgotten. The French say that to part is to die a little. To be forgotten too is to die a little. It is to lose some of the links that anchor us to the rest of humanity.”

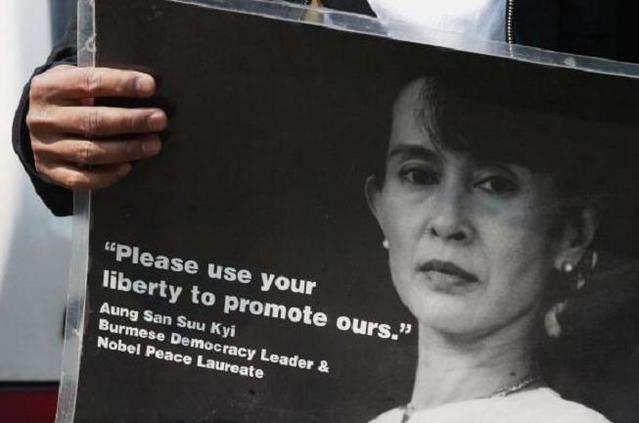

These words were spoken by Aung San Suu Kyi, known to many simply as “The Lady,” at the Nobel Lecture in 1991 when she accepted the Nobel Peace Prize for her nonviolent struggle for democracy and human rights in oppressive Myanmar.

The forgotten groups she spoke of were Burmese migrant workers and refugees. For Suu Kyi, receiving the Nobel Peace Prize meant the world had recognized the plight of these people and acknowledged “the oneness of humanity.” Her personal victory that day was not a tangible prize, but rather a change in attitudes and perceptions

Much of her success in peacekeeping efforts have stemmed from her ability to see not only the diversity but also the equality of humankind. Despite what has now become a common narrative, it is her identity as a woman that has aided her ability to empathize with these vastly different groups of people.

The Lady’s life provides an interesting framework for a story that often goes untold. With her success in peacekeeping endeavors, it would only be reasonable to assess that women are capable of not only filling, but also succeeding, in these global security roles. Yet, despite this assessment, such a conclusion has yet to be agreed upon. In her remarks at the U.S. Institute of Peace, Ambassador-at-Large for Global Women’s Issues Melanne Verveer relayed a quote from a governmental official. The official said, “I don’t get it. They’re [women] not governmental officials. They’re not armed combatants. Why would they be included in [peace] negotiations?”

Beyond the simplified rhetoric, this official addresses a commonly held viewpoint— if women are not actively involved in the conflict, they should not be involved in the resolution. However, the United Nations is working to change these perceptions.

In October 2000, the U.N. passed Security Council Resolution 1325, targeted at increasing representation of women in peace negotiations and all levels of decision making regarding security. These areas include: disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration efforts, inclusion in post-conflict reconstruction, increased protection from sexual violence, and an end to impunity for crimes against women.

This resolution, however, was not the first. Five years prior the Beijing Platform for Action was passed with 189 countries pledging to strengthen “the participation of women in national reconciliation and reconstruction and to investigate violence against women in armed conflict”.

Despite women like Suu Kyi and governmental efforts to expand the role of women in peace and security, women remain severely underrepresented in global conflict resolution. Given that women account for half of the world’s population, this is alarming. Without their perspective, efforts to build a lasting peace are futile.

A special report issued by The United States Institute of Peace in January 2011 found that more than half of all peace agreements fail within the first 10 years of implementation and moreover, 31 out of the 39 active conflict zones see conflict re-emerge after peace settlements have concluded. And in all 31 cases, women were excluded from the peacemaking process. In fact, the United Nations states that women make up less than 3 percent of all signatories to peace agreements.

For some this statistic paints a picture of women’s unwillingness to enter this field. For others who understand societal implications more clearly, this underrepresentation is not due to lack of willingness, but to a lack of access. Women in countries such as Uganda and Liberia are clear examples of those who have been active in fighting injustices, but yet were not allowed to do so in a formal capacity.

This lack of formality is especially devastating given that many of these areas remain the most dangerous places for women. Though more importantly these places also remain the areas of greatest threat to international peace and security, and employ specific violent tactics to target women.

Sexual violence, most notably rape, has become a common weapon of war in many countries. Most recently, the gang rape and murder of a 23-year-old woman in Delhi, India garnered international attention as women’s groups sought justice from the attackers. In addition, they questioned the Indian government’s role in the provision of women’s security. The case in India however is the exception, not the rule. The harsh reality is that cases such as these occur frequently in various countries, but those are met only with impunity and injustice.

While it is tempting to view these women as victims, such stereotyping only exacerbates the larger problem and prevents the world from seeing women as the change agents they have proved capable of becoming. In order to end this vicious cycle, it becomes a categorical imperative that the perception of women must change, and that is one that Resolution 1325 and the U.S. recognize.

In December 2011, the United States became one of twenty-some nations to adopt an action plan to fulfill the resolution. In support, President Obama released the National Action Plan on Women, Peace, and Security and signed an Executive Order to see to its implementation. The U.S. Plan outlines five high-level objectives: National Integration and Institutionalization, Participation in Peace Processes and Decision-making, Protection from Violence, Conflict Prevention, and Access to Relief and Recovery. The plan also stresses the importance of coordination between international organizations, non-governmental organizations, and legislative bodies.

Though still in its infancy, President Obama’s plan has arguably already failed to meet some of its most specifically stated objectives. With the failure of Congress to pass the Violence Against Women Act at the beginning of this year, the idealistic notion of the gender equality and accessibility has clearly been relegated to the back burner as partisanship takes center stage— a partisanship that is mostly male. Though a version of this bill has now been passed, party goals clearly took precedence leaving a legislative void from the time of the bill’s expiration in 2011 to its reauthorization. This failure to achieve a timely congressional compromise does not bode well for future initiatives, though perhaps an outcry is coming.

In recent years the numbers of platforms showcasing the voices of women have risen. TED Talks abound with the thoughts and ideas of feminist giants. Hillary Clinton is considering a presidential run for 2016. This past summer The Atlantic dedicated a cover and a multi-page spread to Anne Marie-Slaughter, who sparked a national conversation addressing the issue “Can Women Really Have it All?” Perhaps as these voices coalesce around a common goal, the efforts targeted by Resolution 1325 and the U.S. Action plan can finally be met. Maybe then, when the “oneness of humanity” is achieved, and only then can we truly hope to foster a stable and lasting peace process.

However, if the progress made so far is indicative of that which is to follow, then it will be the words of Aung San Suu Kyi that will ring true. If half of the world’s population remains left out and forgotten in these roles, then The Lady is right. We, as a nation and as a global power, will inevitably die a little. We will lose a vital link that connects us to the rest of humanity and perhaps even further, we may lose some of ourselves along the way.