In September 2016, months after declaring to run the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election, current Jakarta governor Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama made what he thought was a simple speech about his economic program at a campaign stop in the islands off the coast of Jakarta. Ahok, an ethnic Chinese Christian who assumed the governorship after current Indonesian president Joko Widodo took office in 2014, made the focus of his speech economic policies and what he had to offer Jakarta should he return to the governorship. However, in passing he had mentioned that some people may feel that they cannot vote for him because they are being “deceived about al Maidah 51 and so forth.” This Quranic verse, which states that Muslims should not be allies to Jews or Christians or accept their leadership depending on the translation, had been used by Muslim leaders opposed to Ahok and many had interpreted it to mean that Ahok, a Christian, could not lead the capital city of Muslim-majority Indonesia.

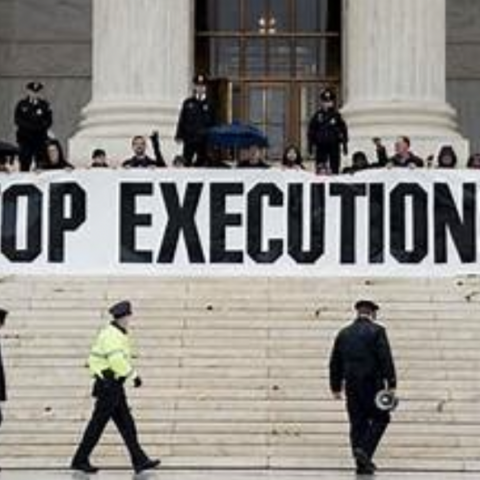

Although the full video of his speech was around a few minutes, Islamic groups around Indonesia began sharing an edited 13 second version of his speech through social media and Ahok soon faced a multitude of calls for his resignation, imprisonment, or even death. By November, hundreds of thousands of Indonesians had taken to the streets demanding Ahok be charged with blasphemy and the government obliged soon after, naming him a suspect in a case of blasphemy and ordering him to go on trial. Protests continued, reaching some of the largest crowd sizes seen in Indonesian history, as many demanded Ahok be detained. On trial for blasphemy with only a few months remaining before the election in February, Ahok saw his poll numbers plummet. He did make it out of the first round with 43 percent of the vote but he lost by over fifteen percentage points to Anies Baswedan in the second round and conceded the election, thus failing in his quest to become Jakarta’s first elected Chinese or Christian governor.

According to some, including Ahok himself, this chain of events would not have unfolded if there was not an election coming up, with Ahok stating that he had essentially written the same statement about al Maidah 51 in his book “Merubah Indonesia” (“Changing Indonesia”) back in 2008 and faced no noticeable backlash. While the proximity of the speech to the election was certainly a unique opportunity for those previously opposed to Ahok to utilize, it is perhaps safer to say that Ahok’s status as a “double minority” (i.e. religious and ethnic) certainly made him an easy target for Islamists and the rising tide of political Islam would have still hampered his campaign. Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim majority country, is constitutionally secular but has since its inception had to walk a fine line between religion and politics. Many see Ahok’s election loss as a victory for political Islam and something which perhaps sets a precedent for religion being used effectively against a candidate. Naturally, some fear this may threaten the liberal democracy Indonesians have enjoyed for nearly two decades.

Of course, if political Islam is to be seen as a threat to secularism and democracy in Indonesia, it is imperative to examine how the role of Islam in Indonesian politics has evolved since its independence from the Netherlands in 1945. When Indonesia first became independent, there were four main actors vying for influence within the government: the military, communists, nationalists, and Islamists. Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno, was a Muslim but was the founder of secular Indonesian nationalism. When Sukarno was devising a constitution and deciding what exactly it meant to be “Indonesian,” he faced large amounts of pressure from Islamic groups who desired for Indonesia to be an Islamic state governed by sharia law. As a compromise, Sukarno made the first principle of Indonesia’s national philosophy Pancasila “belief in the one and only God.” When Indonesia held its first democratic elections in 1955, Islamic parties received nearly 40 percent of the vote but coalition building was next to impossible since four parties had received nearly equal shares of the vote. Meanwhile, Sukarno and his nationalist government were engaged in battle with Darul Islam, an Islamist movement which aimed to do away with Pancasila and transform Indonesia into and Islamic state governed by sharia law. Sukarno, recognizing that governing was impossible with the parliament seats so evenly split and that Darul Islam controlled large parts of the countryside on multiple islands, ushered in the era of “Guided Democracy” from 1957 onward. During the Guided Democracy era, martial law was established, Sukarno became “President for Life,” and the government’s philosophy was simply stated to be “nasakom.” Nasakom, short for nationalism, religion, and communism in Indonesian, was Sukarno’s attempt to once again placate each of the major actors competing for influence in Indonesia and was accepted by many Muslim groups.

Although Islamist movements like Darul Islam had been effectively subdued by Sukarno, his successor Suharto, a general in the military prior to assuming power in 1965, saw all kinds of Islamic activism as serious challenges to his iron-fisted “New Order” rule and forced many groups underground after initial support from Islamic groups waned by the 1970s. Once a key part of Indonesian politics under Sukarno, Islamic parties were forced by Suharto to merge into one government-supervised party called the United Development Party (PPP), which attempted to challenge Suharto’s stranglehold on the government but were always beaten in the elections by Suharto’s party Golkar. Whatever power the PPP had was severely diminished when Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), the largest Islamic organization in Indonesia, withdrew from it in 1984. Soon afterwards, Suharto forced the PPP to replace its religious ideology with Pancasila and cease use of Islamic symbols. Recognizing that stifling religious activism had led to Islam becoming a “political alternative” to express dissatisfaction with his government, Suharto attempted to court the favor of Muslim groups in the 1990s by doing things like making a pilgrimage to Mecca and establishing the a council where Muslim leaders were allowed to voice criticism of him. Despite these efforts, the damage had already been done and many Muslim groups were at the forefront of protests against Suharto until his resignation in May 1998.

With Suharto deposed and democratic elections returning, the intensified beliefs of many Indonesian Muslims resulting from the repression of religious activism opened the floodgates and returned Islamic groups to prominence in the country. Although the Democratic Party of Indonesia-Struggle (PDI-P), led by Sukarno’s daughter Megawati, won the most votes out of all the competing parties, Islamic parties such as the PPP, National Mandate Party (PAN), and the National Awakening Party (PKB) earned a combined total of 31 percent of the vote. On top of that, the former leader of NU and religious scholar Abdurrahman “Gus Dur” Wahid was chosen to be president by the Indonesian parliament in 1999 following the parliamentary election. Although a prominent Muslim cleric, Gus Dur was an adherent of what has been termed “traditionalist” Islam, which preaches pluralism and integrates elements of other religions as well as local culture into the faith. As such, it is generally considered to be tolerant of other faiths and rejects puritanical forms of Islam such as Wahhabism and Salafism (which the NU was founded to combat). Although Gus Dur only lasted a little under two years in office before being removed by parliament, he showed how political Islam in Indonesia does not necessarily have to be sectarian nor divisive. In fact, when Ahok was on trial, his defense team presented a video of Gus Dur discussing al Maidah 51 (in which he states that it does not apply to government leaders) as evidence of Ahok’s innocence.

Moderate Islam did emerge from the Suharto era as the initial victor in the race to win over the hearts and minds of Indonesian Muslims but the reason why many inside and outside of Indonesia are weary of political Islam is because of the growth of orthodox or “modernist” Islamic groups which reject syncretism and adhere more strictly to the Qur’an and Hadith. Although the largest modernist group, Muhammadiyah, is largely devoted to community outreach and non-political activities, it has become increasingly conservative following Suharto’s rule. The Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI), Indonesia’s top clerical body which contains groups like NU and Muhammadiyah, has seen its role in society expand and, likely due to its increasingly orthodox stance, declared that Ahok had indeed blasphemed the Qur’an. Simultaneously, Saudi Arabia has been spreading Wahhabism within Indonesia since the end of Suharto’s rule and groups like the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI), known for carrying out hate crimes against those who do not adhere to their fundamentalist version of Islam, organized many of the protests against Ahok. Despite being essentially an Islamist vigilante group with a reputation for violence, the FPI still has a seat on the MUI and faces no consequences from the government for its actions.

The rise in prominence of orthodox groups is certainly concerning itself but what Ahok’s election loss has proven is this: they are winning through democratic means. In fact, even ten years ago people in Indonesia were readily adapting to a more conservative society where people drink coffee instead of beer and vote for parties which adhere to their chosen view of Islam in lieu of what policies they intend to enact. In the People’s Representative Council, the lower house of Indonesia’s parliament, Islamic parties currently hold 174 out of 560 seats and are part of both the government and opposition. As a result, many of these opportunistic Islamist politicians are clamoring to redefine what it means to be Indonesian, with the PPP proposing that the presidency be closed to all except “natives” (i.e. Muslims since there is no such thing as an Indonesian ethnic group). For ethnic Chinese and non-Muslims like Ahok, the prospect of being deemed something akin to an alien is frightening, yet plausible, as political Islam continues its growth in Indonesian politics through the democratic process. While the rise of Islamism in the country is of concern to many, it is important to remember that it gained prominence through the ballot box, and may very well lose it via that route as well.