Let’s settle one thing first: the U.S. has never been in the business of supporting democracy in the Middle East. Strategic American interests consistently take priority over democracy promotion and human rights (ask the protestors in Bahrain).

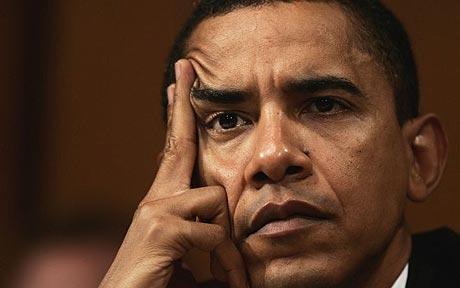

People across the world eagerly hoped for a change in course when Barack Obama moved into the White House, and his famous 2009 speech in Cairo seemed to usher in a new chapter of American foreign policy in the Middle East, guided by respect for self-determination, human rights, and reconciliation. Four years after that visit to Cairo, however, Egyptians’ confidence in Mr. Obama sits at only 26%, a 16% drop since his election, according to a Pew Research poll.

Today, both the Egyptian military government and Muslim Brotherhood sympathizers hold the U.S. in contempt. General Abdel Fatah al-Sisi, Commander-in-Chief of the Egyptian Armed Forces and the real power broker of the interim government, recently stated, “You [the United States] left the Egyptians, you turned your back on the Egyptians and they won’t forget that. Now you want to continue turning your backs on Egyptians?” On the other side, Islamists claim that the U.S. was supportive, if not actively involved, in the overthrow of Morsi’s democratically-elected government. The U.S. has been on the wrong side of both changes of power in the Egyptian government since 2011, and these missteps have weakened the Obama administration’s influence and credibility in the country and the region as a whole.

The first blunder was America’s continued support of dictator Hosni Mubarak in the face of massive street protests in 2011 that led to the downfall of his regime. Strategic interests, namely Mubarak’s support for the current peace with Israel and his regime’s unflinching persecution of Islamists, made the former Egyptian government an important ally in the region, despite its atrocious human rights record. By the time the U.S. decided that Mubarak needed to go, the game was all but over.

The second mistake was the half-hearted response to the recent coup against democratically elected President Mohammad Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood. It looked like a coup and acted like a coup, yet nobody from the White House was willing to call it a coup (beyond the negative connotations, designating the military takeover as a coup would instigate an automatic cut-off of American military aid, to the tune of $1.3 billion a year). In the days after Morsi’s overthrow, American officials gave tacit support to the military’s actions. Secretary of State John Kerry remarked that “the military did not take over, to the best of our judgment – so far. To run the country there’s a civilian government. In effect, they were restoring democracy.” The Africa Union, on the other hand, immediately suspended Egypt from all activities.

Washington’s reluctance to recognize the coup as a coup sends a message to Muslims all over the world that America supports democracy only in so far as it is a democracy that excludes or marginalizes religious groups in the political process. America’s continued Cold War-style realpolitik in the Middle East, under the guise of democracy promotion, is increasingly being seen as the hypocrisy it is, resulting in a loss of American credibility as a negotiator and power broker in the region.

Obama’s policy in Egypt and the rest of the Middle East is fragmented and aimless at best (see Syria), and blatantly duplicitous and harmful to long-term American interests at worst. To be sure, the tumultuous years since the Arab Spring began are not under the control of the American presidency, but diplomatic reactions to the unfolding political climate can set the tone for intergovernmental relations for years to come. Old-school power politics has left the U.S. increasingly friendless in the post-Arab Spring Middle East. The “new beginning” Obama spoke of just four years ago in Cairo seems to have been forgotten, to the detriment of democracy-hungry revolutionaries the world over.