By Vineet Raman

The last decade of American commercial aviation has seen the advent of several foreign airlines, along with the expansion of existing services from foreign carriers in terms of frequency of flights and capacity. Several of these foreign carriers, mainly those based in Europe, have formed joint-venture and codeshare agreements with American airlines — which themselves have become ever more consolidated in the last decade — allowing both parties to market each other’s flights and share the profits. These agreements also receive anti-trust immunity, allowing them to coordinate their schedules and provide convenient flight times for travelers without being accused of collusion.

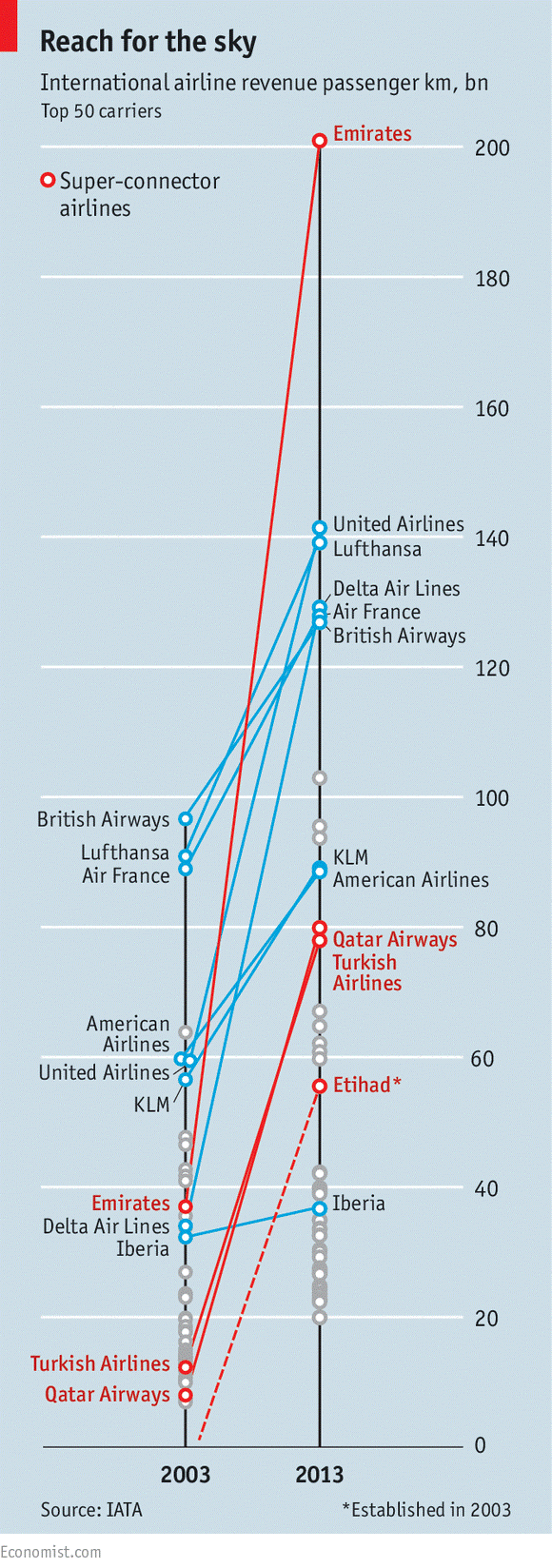

Three noteworthy airlines are the powerhouses of the Middle East: Emirates, Etihad, and Qatar, also known as the ME3. Based in the oil-rich countries of the United Arab Emirates and Qatar, respectively, they have allegedly received $42 billion dollars in government subsidies. The three largest US airlines – Delta, American and United, known collectively as the US3 – have launched an intense campaign to suspend the Open Skies agreements between the United States and the UAE and Qatar. Open Skies agreements allow foreign airlines to determine flight frequencies and capacity without government influence. In the eyes of the US3, the Open Skies agreements have allowed the ME3 to expand rapidly and “dump” their subsidized capacity in the US market.

However, the ME3 claim US airlines have also benefited from government subsidies in the form of bankruptcy protection and fuel refunds.

In Canada, the ME3 are restricted to at most 3 flights per week from a trio of Canadian cities to the airlines’ home bases. This is due to Canada’s protectionist policies, which allow its own Air Canada to continue to thrive with little competition from the ME3.

Delta is in the process of returning seven billion dollars to its shareholders in the form of a current two-billion-dollar share-buyback program and another five-billion-dollar share buyback program to be completed by 2017. With seven billion dollars alone, Delta could afford to buy 21 state-of-the-art Boeing 777-300ERs at list price (though Boeing almost always offers some sort of price cut). These aircraft would modernize its aging fleet, improve its service, and offer routes of longer distances out of its hubs. Instead, it chose to reap the benefits of record profits.

In fact, according to Airways News senior business analyst Vinay Bhaskara, the main point of contention

is the Middle Eastern carriers’ ability to operate “fifth freedom” flights, or flights that originate outside the carrier’s home market. In 2013, Emirates launched a route between Milan and New York, putting it in direct competition with Delta and American, which also operate the route. What’s more, Emirates uses its young, flagship A380 aircraft on the route, while Delta and American continue to use decades-old Boeing wide-body aircraft. The transatlantic market is one of the most profitable and competitive on the planet, so it makes sense that the US3 were suddenly galvanized to action – they fear they cannot compete with the level of service provided on the ME3 carriers.

The ME3 carriers, in fact, are consistently rated among the best carriers in the world. Many of their fleets are composed of new Boeing and Airbus wide-body aircraft, all of which are fitted with an onboard product that is much better than that of the US3. Delta’s average fleet age is 17 years, while Emirates is 6.3 years. All of their cabins are well-reviewed on Skytrax, an airline and airport review site, with Qatar Airways taking airline of the year for 2015. Emirates A380 is perhaps most famous for having a shower spa available to First Class passengers onboard. The multinational cabin crews of the Gulf carriers are among the friendliest and best-trained in the world.

The Gulf carriers contend that, outside of the economic benefits that accompany each of their flights, they support the American economy with their massive wide-body jet orders. In November 2013, Emirates made what is now the largest aircraft purchase in history, ordering 150 Boeing 777X aircraft for a list price of $76 billion each. Emirates claims that this massive order (not including the older Boeing 777 aircraft that have already been delivered) alone will support over 400,000 US jobs.

The row between the US3 and the ME3 has become more intense. In February 2015, Delta CEO Richard Anderson offhandedly suggested that the Gulf carriers and their governments were linked to the terrorists involved in the September 11th attacks. Qatar Airways CEO Akbar al-Baker shot back that Anderson mentioned terrorism in an attempt to “cover his inefficiency in running an airline,” and later tacking on that Delta flies “crap” planes.

According to Tim Clark, CEO of Emirates Airlines, the Gulf carriers have thrived not by siphoning off passengers from the US3, but by creating new markets in areas the US3 did not serve. Conveniently located within an eight-hour flight of about two-thirds of the world’s population (approximately five billion people) the Gulf carriers are inherently well-positioned to grow by offering one-stop itineraries that funnel passengers through their central hubs. For example, the Gulf carriers are the only airlines offering one-stop connections from the US to destinations in rapidly developing countries. Emirates alone offers service from nine U.S. cities to ten cities in India via its convenient hub in Dubai—more than the US3 and their European codeshare and joint partners combined.

The US3 have only ever directly competed with the ME3 on two routes: Milan to New York (with Emirates competing against American and Delta) and Washington to Dubai (with Emirates competing against United). Elsewhere in the Gulf, United operated a thrice-weekly service to Bahrain and Kuwait. Delta had its own nonstop service to Dubai from Atlanta until it announced in October 2015 that it was canceling it effective February 11, claiming “overcapacity on U.S. routes to the Middle East operated by government-owned and subsidized airlines.” United quickly followed in December, canceling its Dubai and Kuwait-Bahrain service, claiming lower profits due to the entry “subsidized” carriers. Many saw this as a publicity stunt to bring more support to their cause.

With the withdrawals of Delta and United, the US3 have put on a great show. Both carriers canceled their only two routes that could have shown a semblance of competition with the ME3, claiming that the “subsidized capacity” being brought in by the ME3 created a distorted playing field, even when statistics show their routes to the Middle East were doing fine. So why the spectacle? To gain the sympathy of the US Department of Transportation.

Ultimately, the American federal government will have to decide how to proceed with the Open Skies agreements. The US3 want to discuss their terms once again, while the ME3 want to leave them as is and continue their meteoric expansion. Richard Anderson, CEO of Delta, has said he would prefer “fair skies” over “open skies.” Analysts like Bhaskara believe the federal government will side with the ME3, as they provide American consumers with more choices and in the long-haul lessen the cost of travel to several developing economies.