By: Robert Jones

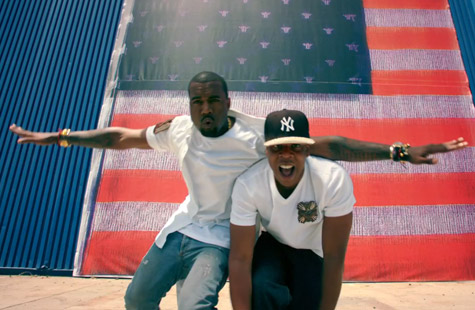

Rappers know a thing or two about making money and they are not too bashful to say so. Artists as old as 2pac and A Tribe Called Quest and as modern as Future and Drake have flaunted their new-found wealth. The music of these nouveau riche up-and-comers is always changing, as is the marketing. No contemporary rappers can claim as wide a cultural cache as Jay Z and Kanye West, the twin titans of pop rap. When Ye and his Big Brother released new albums this summer they announced a new paradigm of hip-hop marketing as only they could.

Kanye West’s Yeezus was destined to be one of the hottest releases of the summer. West kept details private, releasing information little by little in the most enigmatic way possible; a lone tweet alluding to a possible album release date, a surprise screening of a new music video via announced projections across the world, and seemingly endless talk on blogs speculating collaborators and song titles. This was marketing a la Project Mayhem. When Yeezus was finally released, it charged out into the public consciousness and was almost inescapable. Critics adored it, every hip hop fan had an opinion, and for the first time in years the public couldn’t stop talking about a single 40-miute collection of music. The album rejected the current trends in hip-hop, instead moving forward with previous Kanye ideas like Jamaican samples and electronic, edgy production. Perhaps because of its unconventionality (both in promotion and content), Yeezus was the least commercially successful of Kanye’s six studio albums. But the fearless voice of our generation was not dismayed. Weeks later he claimed one of the album’s verses as the best 16 bars in all of rap music, firmly set in his belief that he was always as good as he said he was. He is a god, after all.

West’s mentor and label mate Jay Z attempted to promote his album with a similarly provocative campaign, with less success. Exclusive pre-release privileges for this summer’s Magna Carta… Holy Grail. Early releases were given to Samsung phone owners (a deal that meant $5 million in sales for Roc-a-fella Records). Jay even filmed a ten minute music video/short film with several top performance artists and filmmakers. People did not greet this with the same reverence they felt for Yeezus. Music journalists noted the cognitive discord created by Jay Z’s exclusive release partnership with Samsung, a major phone company, and a short film featuring some of the most famous artists in the avant garde community. Instead of exploring the dynamic between these two worlds, Jay Z simply continued referencing famous artists like Jean-Michele Basquiat as if he himself was still a visionary and groundbreaking artist. The album received mixed reviews, with many noting that Jay Z’s posturing and bragging seemed empty. The public’s jaws dropped with Yeezus; with Magna Carta they rolled their eyes.

So, what’s a young musician to do? Kanye and Jay Z set out two paths: go as big as possible without sacrificing your anti-corporation ethics, or embrace the corporations and become a business, man. Even though that choice might sound obvious, the sales numbers from each album might sway an upcoming rapper in a different direction. Yeezus sold a decent amount in its first week then experienced a huge drop in sales. In contrast, because of Jay Z’s partnership with Samsung, he can boast that Magna Carta sold 1,000,000 copies without lying since the company bought that many copies to distribute to its customers. Few would deny that West is more popular than Jay Z at the moment, but the unconventional promotion of Yeezus still could not compete with the massive Samsung-fueled Magna Carta. This might send a troubling message to rising artists; despite the growing trend of releasing music for free or through online means, big profits can only come through corporate partnership.

Maybe this is not such a cause for alarm. Jay Z and Kanye West are superstar rappers who could sell thousands of records regardless of their music or marketing, and the rise of sites like Soundcloud and Bandcamp has made free mixtapes a conventional way for rising rappers and producers to release music. Frank Ocean is a notable example of a big-name artist who mostly avoids the spotlight but maintains his notoriety, especially given his historically open sexuality. However, even he has a Tumblr where he frequently posts notes and letters to his fans. This connection to fans is the same thing that Kanye wanted when he projected his face on the side of buildings in New York and Chicago, and when Jay Z agreed to give an exclusive pre-release to Samsung customers. Just as many rappers are accompanied by a hype man when they appear live, the promotion of their content builds anticipation. If an artist intends to change the game, they’re going to have to change how they reach their fans. And the most important lesson?

Hurry up with the damn croissants.