By Rory Hibbler

Leonardo DiCaprio’s latest film, The Revenant, is gaining recognition as the film that may win him an Oscar. It shows the brutality of wars between American Indians and white traders in early America. With the exception of Pocahontas, it seems most blockbuster movies, including The Revenant, involving colonizer-indigenous relations are focused on the white heroes braving savage lands. For example, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom portrays indigenous people as cannibals and unrestrained, and in Peter Pan the Native American chief is colored bright red. Sadly, this pattern holds true off the screen as well. The development of America witnessed European colonizers pushing American Indians into the shadows, and now modern day America is not boding much better; the only times these cultures seem to get public attention is when Hollywood puts them in a movie at war with a beloved famous actor.

We’ve all read about the gruesome history of American Indians and colonizers in social studies textbooks. Generally, the textbooks leave off with ‘Andrew Jackson sent them to reservations out West’ and never mention the subject again. If we look at the picture now, however, it doesn’t hold up much better than back in the 1800s.

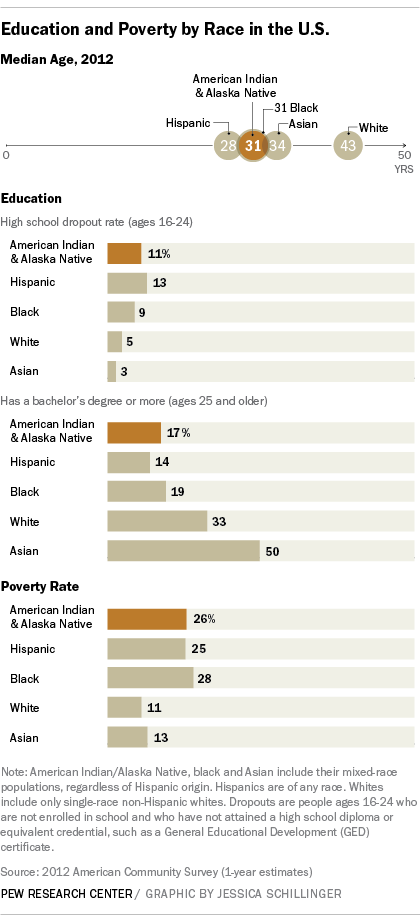

To start, the economic promise on reservations is scarce: Up to 80 percent of adult American Indians living on reservations are unemployed; almost 30 percent of families live below the poverty line; 40 percent of housing is ‘inadequate’; and American Indians are 82 percent more likely to commit suicide than other Americans. When people are faced with dire conditions like these, they turn to crime. This leads to a mass incarceration in these communities – then further complicated by the mixture of federal and tribal jurisdiction, which occasionally causes people to be punished twice for the same crime. These frustrations also cause sky-high alcoholism on reservations, and American Indian families are plagued by domestic abuse to the point that it’s a public health crisis: 1 in 5 American Indian children suffer PTSD and the women are 3.5 times more likely to experience sexual assault than in any other ethnic group.

How did it get to this point for American Indians, and why does their plight often get so little national attention? Because the federal government continues to stand in the way of American Indian interests, even in a far more tolerant modern era.

The federal government still takes away promised land from American Indians, such as in Hawaii in which the government attempted to take sacred land from the Mauna Kea to build a telescope, or the infamous Black Hills where the government attempted to buy $1.3 billion worth of land from the Sioux (which they refused). Every politician has an opinion on the Keystone XL pipeline, but none seem to bring up the fact that it cuts across Indian country and is vehemently opposed by the National Congress of American Indians.

Land is not the only problem: American Indian’s lack of property laws prevents any real economic development. Beneath a country built on capitalism lie communities without such a concept. Most reservation land is communal—there are no home titles and no way to make loans because nobody owns any collateral in the form of land. Without private property, most reservations are filled with substandard trailers and lack business development.

Even if an American Indian entrepreneur could gain enough capital to start a business, all development on reservations must go through American bureaucracy, involving four different agencies and almost 50 steps. This could take several years, which would discourage even the most ambitious of capitalists.

The United States government continues to squander any hope in American Indian communities of surviving in a land they once ruled. For any true change to come about, there needs to be intensive legislative reforms in the way we deal with both tribal and national governments. Those legislative reforms need to be decided based on what’s best individually for each tribal nation of the American Indian population. To start, there should be a far more streamlined process to gain a loan on reservation territory and build a business. Economic development must be encouraged, not squandered.

The United States government continues to squander any hope in American Indian communities of surviving in a land they once ruled. For any true change to come about, there needs to be intensive legislative reforms in the way we deal with both tribal and national governments. Those legislative reforms need to be decided based on what’s best individually for each tribal nation of the American Indian population. To start, there should be a far more streamlined process to gain a loan on reservation territory and build a business. Economic development must be encouraged, not squandered.

Already, the Congress of Native American Indians has a campaign to increase financial education on reservations. They also have campaigns to help inadequate housing, unemployment, and so many other plights American Indians face. Once the reservations are given avenues to lift themselves out of poverty, the socioeconomic issues will begin to diminish.

In the meantime, perhaps we, the American people, could at least stop the slew of offenses like creating movies focused solely on white men’s triumphs over American Indians and wearing offensive culture-appropriating headdresses to Coachella. We can decrease the outwardly racist sports team names or avoid making logos that are visual interpretations of a racial slur. And we can curb our bias and seek to understand the incredible indigenous cultures that have suffered so much by our hands.