By Ariel Pinsky

On August 26, Arutz Sheva (Israeli National News) reported that three of the last remaining Jewish families in war-torn Syria have been evacuated to Louisville, Kentucky, after posing as Christian Arabs to gain entrance into Sweden. A Louisville synagogue, with the help of local and foreign authorities, helped the six adults and seven children complete the final leg of their covert journey to resettle in the United States and escape the ongoing war back home.

The current Syrian conflict has propelled the tragic refugee crisis into the international spotlight and resulted in a humanitarian emergency in which hundreds of thousands of civilians, including thousands of children, have been killed since the civil war began in 2011. Last year, CNN estimated that only 18 Jews remain in Syria—if the families were included in that count and assuming that no Jews have entered Syria since, that would leave a total of five Jews in all of Syria today.

It seems only natural to assume that a sizable Jewish population in Syria, one of Israel’s most formidable enemies in the latter half of the 20th century, likely never existed at all—yet nothing could be further from the truth. The Jewish community of Syria dates back to Roman times and includes a rich history and culture that has remained relatively intact through close-knit immigrant Syrian communities in the U.S. (particularly Brooklyn), Israel, Mexico, Brazil, and Panama.

At their peaks, the thriving Jewish quarters in Damascus and Aleppo once boasted over 20 synagogues and an estimated quarter-million Jews, primarily a mix of Mizrahi Jews (Jews of Syrian and Middle Eastern descent who have inhabited Syria from ancient times) and Sephardi Jews (Jews of Spanish or Portuguese descent who fled Spain when all Jews were expelled during the Reconquista in 1492).

These communities persisted into the Ottoman period, but began to wane around the latter half of the 19th century after the completion of the Suez Canal, and the resulting declining commercial importance of Damascus and Aleppo as major Middle Eastern trade routes shifted from Syria to Egypt. By the time Israel was established in 1948, Syria’s 40,000 remaining Jews were continuing to leave Syria, but for primarily non-economic reasons. Several families sold their businesses and their homes as a direct result of increasing Arab aggression and restrictions on travel and property rights by the new Syrian government – Syria gained independence in 1945 following the end of the French mandate for the former Ottoman-controlled territories of Syria and Lebanon.

The new government imposed restrictions on Jews reminiscent of those enacted across Europe prior to the Holocaust less than ten years earlier: Jews were not allowed to work for the government or banks, could not acquire telephones or driver’s licenses, and were barred from buying and selling property. Several Jewish bank accounts were frozen or liquidated, an airport road was built over an ancient Jewish cemetery in Damascus, and many Jewish schools were ordered closed. Teaching Hebrew was forbidden, and a Mossawi (“Jew” in Arabic) stamp was imprinted in big red letters on all Syrian Jews’ identification cards.

Travel by Syrian Jews was restricted domestically and internationally: Syrian Jews had to leave at least one family member behind and post bonds of $1,000-$3,000 per person if they wished to travel outside of Syria, and Jewish emigration out of Syria was outright banned. Additionally, the once-independent Jewish quarters in Damascus and Aleppo were being heavily monitored by the Mukhaberat, the Syrian secret police.

When the United Nations voted to partition Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state in 1947, ancient synagogues in Aleppo were burned down and vandalized, and attacks against Syrian Jews escalated. 7,000 of Aleppo’s 10,000 Jewish residents illegally fled from their native land and smuggled out historical Jewish texts and artifacts, including a Bible written in 1260 known as the Aleppo Codex. Two years later, a terror attack involving a bomb placed at a Damascus Synagogue resulted in the death of 12 Syrian Jews and countless others wounded. The event shocked the Jewish community of Damascus and resulted in even larger waves of covert Jewish emigration to cities in North America, Turkey, Lebanon, Israel, and Latin America.

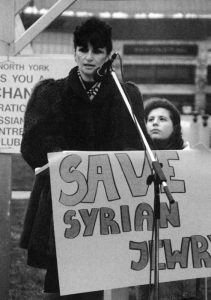

Syrians continued to illegally emigrate throughout the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s. After the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, in which Syria lost control of the Golan Heights, armed Palestinians broke into the homes of Syrian Jews, and harassment from Syrian intelligence officers and other government officials increased. Canadian activist Judy Feld Carr is credited with helping to smuggle 3,228 Jews out of Syria during this time by arranging for (often fake) passports and visas, quietly raising money from donors in Canada, and creating an underground information network in Syria complete with its own coded language in order to operate under the authorities’ radar.

In 1992, conditions began to improve for Syria’s remaining Jews when Syrian President Hafez al-Assad (current President Bashar al-Assad’s father) lifted the travel ban imposed on the country’s then-4,500 Jews. According to the U.S. State Department, the American Embassy in Damascus immediately issued visas to a number of Jewish refugees following the decree. Assad agreed to lift the ban on the condition that the emigrants would not be allowed to resettle in Israel. In short, relations between Syria and Israel were tumultuous at best during the openly anti-Zionist Hafez al-Assad’s rule.

Though Hafez al-Assad is often remembered today as a brutal dictator much like his son, his announcement in 1992 signaled a major shift in Syria’s policy toward its Jewish citizens. The removal of the 45-year ban was an attempt to bolster Syria’s position in Middle Eastern peace talks and may have been hastened by pressure from foreign governments such as the United States and the international media. Journalist Robert Tuttle wrote in his master’s thesis at Columbia University, “Indeed, Syria’s Jews became something of diplomatic bargaining chip that the Syrian government could play when it wanted better relations with the United States or an improved negotiating position with Israel.”

Shortly after Assad’s decree, the New York Times reported, “Slowly and quietly, the first of 4,500 Jews given the freedom to leave Syria have arrived in Brooklyn, where the largest Syrian Jewish community in the world has welcomed them with a mixture of joy and relief, and trepidation for those still left behind.”

Though conditions had slightly improved under Assad’s rule, Syrian Jews continued to abandon their homes until 1994, when President Bill Clinton negotiated the arrangement of exit visas for Syrian Jews with the Syrian government (the lifting of the travel ban in 1992 technically allowed for travel only, not permanent emigration).

Today, Syria’s old Jewish quarters are almost completely abandoned and full of broken-down buildings and dilapidated storefronts with few traces of the flourishing Jewish communities that once flourished there. ISIL, Bashar al-Assad’s forces, and rebel groups have destroyed many of the last remaining Jewish structures, including Syria’s oldest synagogue, the Eliyahu Hanabi Synagogue in the historic Jobar neighborhood of Damascus. The synagogue contained many ancient Jewish scrolls and texts that are now feared to be lost forever.

What is not lost is the rich culture of the Syrian Jews that has endured the waves of persecution and exile and can still be found in resettled communities across the world. For example, the musical maqam, or melodic pattern, is still heard in prayers as well as Mizrahi songs played at Syrian Jewish weddings and celebrations; the traditional cuisines of kibbeh, yebra, borekas, and lahmagene are prepared at home and in local Syrian restaurants; distinct phrases embellish everyday language in communities such as Brooklyn’s Syrian neighborhoods, and traditional hymns (Pizmonim) and prayers are recited and remain intact.

Although any hopes for Syrian Jews of a return to Syria have been shattered by the current conflict, the recent evacuation symbolizes a long-awaited end to Syria’s original refugee crisis, one that extends far beyond the ongoing Syrian civil war.