By Ben Diamond

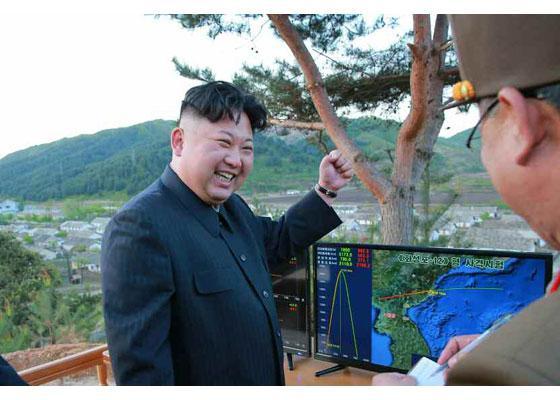

Tensions with North Korea seemed to have eased temporarily after the flash storm of paranoia that enveloped the world last week. North Korea dominated news headlines as Chairman Kim Jong Un and President Donald Trump exchanged inflammatory statements. On August 8th, Trump stated that any more threats that North Korea makes will be “met with fire and fury like the world has never seen”. Kim responded to this threat with one of his own, declaring North Korean intentions to test missiles near the US territory of Guam in the Pacific Ocean. Since then, Kim has stated he is willing to “watch [American actions] a little a more” before following through with any kind of attack.

This is not the first time North Korea has made threats against the United States. In March of 2013, Pyongyang threatened to attack the United States with “lighter and smaller nukes.” In April of that same year, the DPRK’s army claimed that they now officially had the capability to attack the United States with a nuclear strike. And even back in January 2003 when the DPRK left the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), it stated that retaliatory American action would “finally lead to the third world war.”

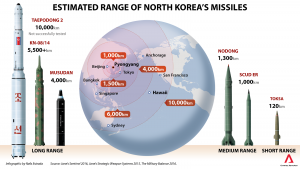

With the US Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) analysis last month that confirmed North Korea’s ability to miniaturize a nuclear warhead for missile purposes, North Korean nuclear threats do not seem quite so outlandish. With President Trump tweeting that military solutions are “locked and loaded” and the US Pacific Command tweeting that US bombers in Guam are “ready to fulfill mission if called upon to do so”, it seems the United States may be on the brink of war. Even though Kim has since put the attack on Guam on hold, tensions are still strong as Defense Secretary James Mattis reiterated that a DPRK strike on a US territory “could escalate into war very quickly.

What is critical for the decision makers in the United States government to do is not overreact; war with North Korea will not happen unless the United States makes a move first. What is sometimes misconstrued is the reason the Kim regime is so set on achieving nuclear capabilities. Kim Jong Un is not CBRN-armed (chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear weapons) terrorist attempting to incite the apocalypse like the Aum Shinrikyo cult in Japan in 1995. Kim Jong Un is not a part of a terror organization with beliefs rooted in an apocalyptic future like ISIS. Kim Jong Un is the dictatorial leader of the most isolated country in the world, with a crippled economy, and very little bargaining power in the international sphere.

Kim could be developing nuclear weapons to attack the United States, as they often threaten to do, or Kim could be developing nuclear weapons for a much more reasonable purpose: the survival of his regime. Siegfried Hecker, director emeritus of Los Alamos Laboratory, and former North Korean nuclear facilities inspector emphasized the rationality of Kim Jong Un in an interview with the Washington Post, stating, “he’s not crazy and he’s not suicidal, he’s not even unpredictable.” All Kim Jong Un need do is look at the fates of Muammar Qaddafi, former Prime Minister of Libya, and Saddam Hussein, former President of Iraq, once they surrendered their nuclear ambitions in the face of U.S. pressure. Qaddafi was dragged out of a hole and beaten to death by opposition forces in the Libyan Civil War, while Hussein was executed by hanging for crimes against humanity.

If Kim’s main goal is regime survival, which recent assassinations of potential threats to his rule (seen here, and here) and the advancement of the DPRK’s nuclear program show to be the case, then North Korean activity in this scenario is perfectly rational. Furthermore, under the stated assumption of regime survival, even when North Korea transitions to a fully capable nuclear power, they would not use a first strike against the United States.

There is a litany of academic literature about nuclear deterrence stemming from the Cold War. Nuclear deterrence is essentially the idea that two states with nuclear weapons (in the Cold War this was the US and the Soviet Union) would never fire a first-strike nuclear attack due to the ability of the other nuclear-armed state to retaliate with a nuclear attack of its own. This isn’t an analysis of the benefits or costs of nuclear deterrence-based peace (for more on that see Kenneth Waltz and Scott Sagan’s analysis). Nuclear deterrence does not fully fit the U.S.-DPRK relationship yet due to the lack of knowledge of North Korean delivery vehicles or specific capabilities, but it does help understand why a nuclear armed North Korea in the future would not initiate a first strike on the United States.

Logically, it plays out very simply. Kim Jong Un cares about regime survival and leadership continuity more than anything. He’s even gone to the point where he killed his uncle who was his mentor and helped solidify his leadership following the death of Kim’s father. Kim has seen other leaders who were similarly detested by the United States end up dead once they gave up their nuclear ambitions. For this reason, Kim would logically want to keep up his nuclear ambitions. Furthermore, once his nuclear ambitions are fulfilled, if he used a first strike on the United States, or a US ally, it would be met with retaliatory strikes (either nuclear or conventional), leading to the demise of the Kim Jong Un regime. Kim Jong Un is not a conventional leader. He is a paranoid dictator, but like all dictators, he likes power, and initiating a nuclear attack immediately puts that position in danger

North Korean rhetoric and nuclear capabilities are not a direct threat to the United States or it interests. Although not ideal, the DPRK is past the point of no return: they will be a nuclear-power soon. The presence of a nuclear North Korea will not be the cause of World War III or an attack on any American interests.

All of that goes out the roof though if America instigates a conflict that could spiral out of control. As Hecker denoted in his interview with The Washington Post, “The real threat is we’re going to stumble into a nuclear war on the Korean Peninsula.” Defense Secretary Mattis and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson understand this and attempted to reassure the American public with an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal on August 13th, advocating their new policy of “strategic accountability.”

Strategic accountability sounds like a practical concept, but as Jeffery Lewis, Middlebury Institute of International Studies and nuclear security expert tweeted in response to President Trump’s “fire and fury” statement: “Your daily reminder that Trump has authority and ability to order the use of nuclear weapons with no second ‘vote’ required.” Trump has a history as President of ignoring his advisors and improvising statements, but to this point, these improvisations have been mostly rhetorical.

In international affairs, actions matter more than words, and Trump has yet to improvise an action with meaningful consequences that went against the advice of his advisors. The worry is still, harking back to Hecker, that we accidentally end up at war. The cause of a militarized conflict with North Korea will not be its possession of nuclear weapons. The cause of a conflict will be what the United States does because of it.