True crime has experienced a boom in the last half decade thanks to shows like “Making a Murderer,” the podcast “Serial,” and three upcoming documentaries about the 1996 murder of JonBenét Ramsey from CBS, Investigation Discovery, and A&E. These shows and podcasts have been fodder for water cooler discussions about the innocence and/or guilt of multiple different parties and the painful, oftentimes grisly details of the cases. The question is: should these instances of real-life crime be treated with the same entertainment interest as the best candidate for the Iron Throne?

This question has arguably existed since the beginning of the true crime genre, but has experienced new relevance especially since last year’s HBO documentary series “The Jinx.” Following the murder suspect Robert Durst (he was suspected of murdering his wife, Kathie, writer Susan Berman, and his next-door neighbor, Morris Black), Andrew Jarecki — writer and creator of “The Jinx” — reopens these cases by sitting down with Durst over the course of a couple of years, ultimately leading to the now-famous admission of guilt by Durst in the finale of the show. “What did I do? I killed them all, of course,” Durst admits after excusing himself to the restroom in the middle of an interview with his microphone still on. Durst was then arrested the day the finale aired, leading many to question how much Jarecki actually knew and when he knew it.

The same could be said for the podcast, “Serial,” which also uses questionable ethics to increase the drama. Throughout the podcast, Sarah Koenig — host and primary investigator of “Serial” — openly addresses her own biases; she qualifies a lot of her discoveries and interviews with Adnan Syed (the suspect convicted of the crime) with statements on how she fluctuates between believing he is guilty, or believing that there was a serious miscarriage of justice. These statements reflect how the listener engages with the content as well, serving to increase the drama of the investigation.

When these subjects of investigations turn from real-life people to characters in a story, how do we reconcile the tragedies that become sensationalized for our entertainment. Is it ethical journalism? Is it truly in the public’s best interest if we continue to view true crime from the lens of a viewer watching TV, and less as concerned citizens? When we debate the guilt or innocence of JonBenét’s mother, are we really contributing to the narrative or are we exploiting the families of the victims for our own entertainment?

Because of the serial nature of these television shows and podcasts, the viewer/listener is invited to trace all of the gory details of these murders and decide for herself whether she believes the perpetrator is guilty. As Anna Leszkiewicz asks in her article for “New Statesman,”

“Do we want to know every gory detail of these crimes because we care about the victim, or because it excites us? Do we crane our necks at grieving parents for our own entertainment? Is it inherently unethical to treat real lives as spectacle? Aside from general distastefulness, what practical impact does taking evidence out of the courtroom, and into the laps of a potentially limitless audience, have over a case? What are the benefits, and the dangers, of deciding that the law is wrong?”

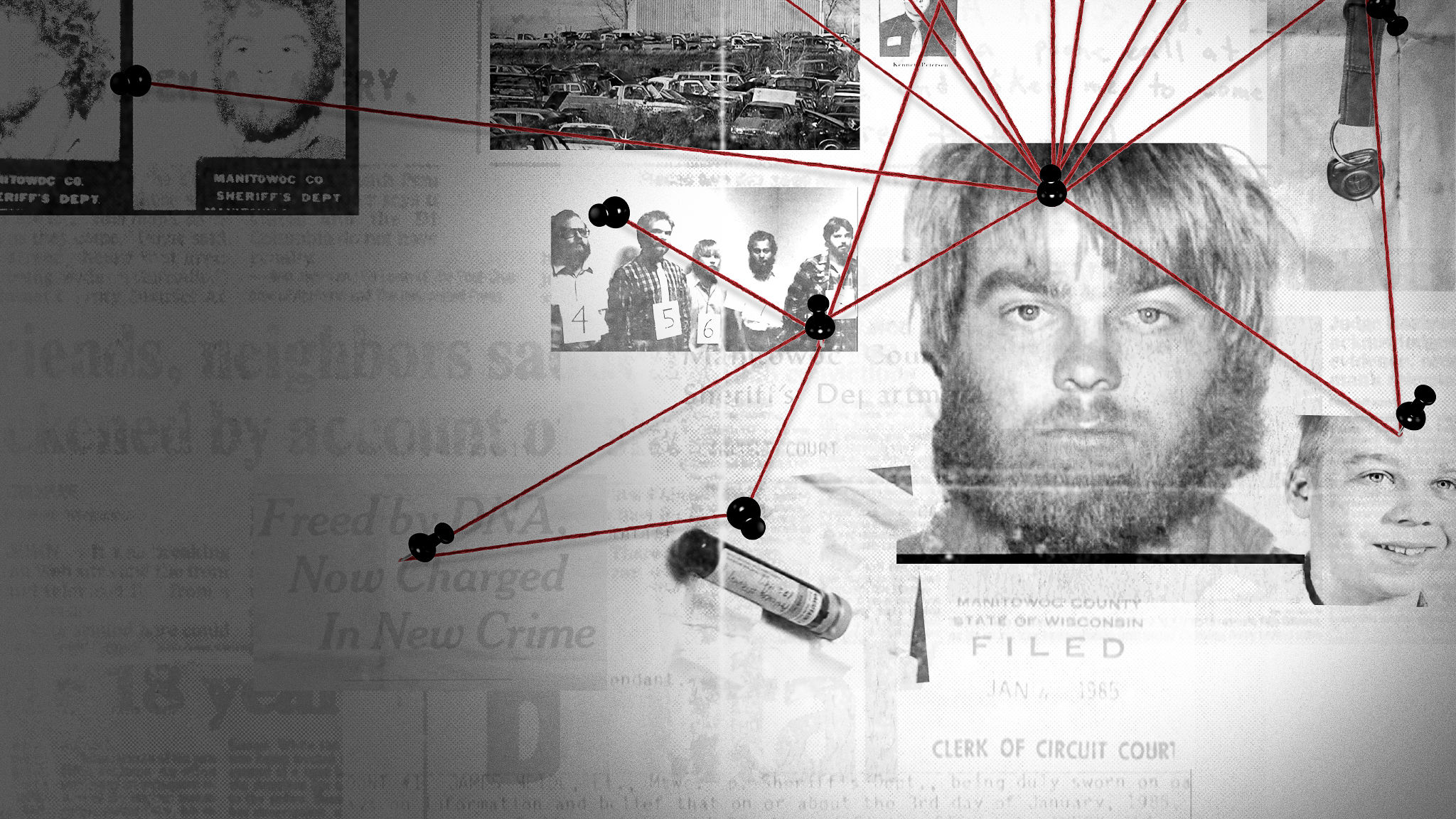

Indeed, the audience’s perceptions of these stories are filtered through the perceptions of the storytellers themselves. These storytellers can openly admit their own biases — like Koenig — or can operate under a presumption of objectivity like Jarecki or the creators of “Making a Murderer,” Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos. All of these storytellers worked very closely with their subjects (Robert Durst and Steven Avery, respectively), and have been accused of letting their subjectivity manipulate details of the cases in order to make a better story.

If the details of these investigations are taken out of the hands of the police and into the hands of the public, and the presumption of guilt and/or innocence out of a jury and into the streets, then how objective can these investigations truly be? When we debate the outcomes of these cases with the same attitudes as we debate the outcomes of our favorite fictional shows, then we may forget that at the end of the day, a real person is still dead. Is it easier for the public to accept these people with the same simple characteristics as a fictional character, while ignoring the complexities of real-life people?

The ethics of true crime TV can be approached from both a pragmatic perspective (is the democratization of the criminal justice system a good thing?) and a moral one (do we care about the victims, or would we rather just explore the grisliest parts of human nature because it’s exciting?) Will true crime narratives help explain and bring justice to the murders of Teresa Halbach (“Making a Murderer”), Hae Min Lee (“Serial”), Kathie Durst (“The Jinx”), and JonBenét Ramsey? On the other hand, they may allow subjectivity in journalism to blur the lines between actual acts of horror and our own entertainment.

The purpose of this article is not to answer any of these questions; indeed, it would be quite presumptuous of me to decide that I have all the answers. It is also not to point fingers. I myself have indulged in the true crime genre and found myself asking, “Did Steven Avery really do it, or was he taken advantage of by a broken criminal justice system that disadvantages people of a certain socioeconomic class?” The point of this article is not to pass judgements, but rather to remind viewers that while these cases can be titillating, we should remember that a crime was still committed, whether or not the perpetrators are guilty. We should consider what place – if any – the general public should have in a murder investigation, and whether treating these real life happenings as entertainment is beneficial to us, the viewers or to the victims and their families in their search for justice.