By: William Robinson

Since the end of the 19th century, no nation has challenged U.S. supremacy over the Americas. The United States’ position as the hegemon of the Western Hemisphere was won with an expansionist policy. By conquering, purchasing, and annexing territories, the United States amassed the potential to become a hegemon, but it did not truly earn the title until it kicked the European powers out of its realm of influence. Though the Monroe Doctrine stated in 1823 that European powers could not intervene in the Western Hemisphere, the United States was too weak to enforce it until the late 1890s. In 1898, it went to war with Spain over control of Cuba. The Spanish lost soundly, forfeiting their control over Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. With this victory, the United States became the modern era’s only successful regional hegemon, free from neighboring threats and unchecked in exerting its regional influence.

Since its accession to this privileged position, the United States has worked to thwart other countries’ attempts at hegemony. In World War I, it aided in preventing Germany from claiming dominance over Europe. In World War II, it stopped Nazi Germany from doing the same and kept Japan from becoming the central power of Asia. During the Cold War, it worked to contain the Soviet Union, keeping it from dominating Eurasia. Through covert operations and strategic partnerships in the Middle East, the United States also worked at various times to contain Iraq, Egypt, and Iran to avoid facing a dominant power in the Middle East. Thus, U.S. policy concerning rising powers has been clear and consistent, and the South Pacific is no exception. As a Congressional Research Service report put it, “Since World War II, the United States has sought to prevent any potential adversary from gaining a strategic posture in the South Pacific that could be used to challenge the United States.” Keeping with this policy, the United States has turned its attention to China.

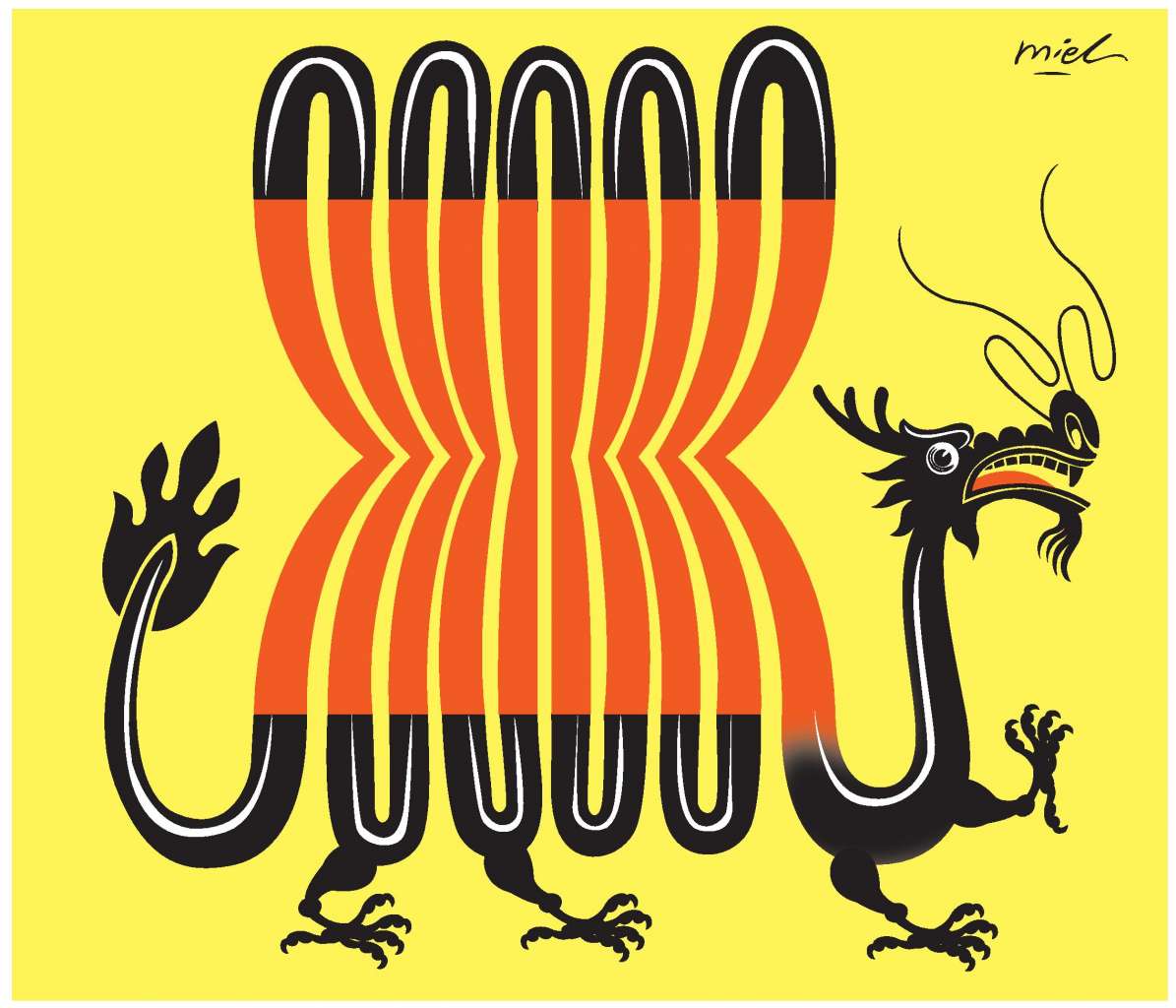

China is undoubtedly the closest to a new regional hegemon in the world today. Its economy is the second largest in the world; its military expenditure is ballooning; its foreign aid and investment reach to every region of the world; its population is still the largest in the world; and it is implementing new international organizations and institutions to rival Western dominated ones. Furthermore, China’s posturing has become increasingly aggressive – provocative military maneuvers, high profile purchases of various military technologies, anti-American rhetoric, and an escalating series of confrontations over islands in the South China Sea. But just as with late 19th century America, China must push out the foreign power before it can claim hegemony over its neighbors, which in this case is the United States.

The most direct sign of U.S. influence in Southeastern Asia is the presence of the U.S. Navy, and this is the first target of China’s increasing power. China’s military spending in recent years has focused on missile technology. Anti-ship ballistic missiles and anti-ship cruise missiles, the prize jewels of the Chinese arsenal, are capable of firing from mainland China and sinking aircraft carriers hundreds of miles out to sea. China has also heavily invested in submarine technology. Both of these technologies are aimed not at confronting the U.S. Navy, but at pushing them further from China’s coast. This in turn gives the Chinese military more freedom to intervene in their neighbors’ affairs without American interference. In 2011, China christened its first aircraft carrier – a Ukrainian hand-me-down of almost no strategic value. The vessel’s true value, however, is as a symbol of Chinese resolve and growing power. In the words of U.S. Navy War College associate professor Andrew Erickson, “Politically… even a single Chinese aircraft carrier could have significant implications for American interests in East Asia. The message to the region implicit in the sailing of a Chinese aircraft carrier – the essence of a rising China with increasingly capable naval power – will demand a still-more-compelling response from the United States.”

China is not only trying to replace the U.S.’ military role in the region, it is also attempting to supplant its soft power role. In the recent summit meeting of the Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation, China presented an alternative to the U.S.-led Trans-Pacific Partnership called the Free-Trade Area of the Asian Pacific. China has also led an effort to create an alternative to the International Monetary Fund with the other BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and South Africa).

To combat the rising hard power of China, the United States must redesign its fleet tactics. Carrier-centric naval strategies present massive and easy targets for new missile technology. Smaller fleets capable of doing covert, quick strikes would be a more effective fighting unit in the Pacific than the immense carrier-centric fleet. At the same time, however, the show of power must also be used as a tool of deterrence – a purpose to which the current, large warships are better suited. The U.S. Navy would also benefit by integrating missile intercepting technology into its fleet capabilities. Admiral Jonathan Greenert, Chief of Naval Operations, stated in a 2013 interview, “We often talk about what I would call hard kill – knocking it down, a bullet on a bullet – or soft kill; there is jamming, spoofing, confusing, and we look at that whole spectrum of options.”

To combat the rising soft power of China, the United States must put fewer conditions on its foreign aid. This form of assistance will likely become a tool to compete for allies in the blossoming rivalry between the United States and China in the future. China’s investments and aid are largely conditional on only getting access to the receiver country’s resources or markets. Issues such as regime type, human rights provisions, democratic institutions, and transparency are non-issues for Chinese aid, but they often hinder receiving American aid. While U.S. aid policies should not completely ignore these factors, they cannot be as focused on demanding immediate change before giving aid. As in the Cold War rivalry with the Soviet Union, non-strategic factors will take a back seat when considering with whom the United States will ally itself.

The United States claimed its supremacy over the Western Hemisphere by wresting control of the Caribbean from Spain. Spain was in decline; the United States was on the rise. Over a century later, China has become a potential hegemon, and the United States has become the foreign power in the way of regional hegemony. The United States is not in the state of decline that the Spanish empire was, but China is rising in power. Will the United States have the determination to increase its presence in the Pacific while also combatting ISIL and containing Russia? Will it be as resolved to prevent Chinese hegemony as it was German and Soviet hegemony? Time will tell.