What is the biggest ecological threat facing the world today? Is it humans’ threats to nature such as climate change and fragmentation, or natures’ threats to humans- as in deadly epidemics? Perhaps it’s a bit of both as civilization and nature are are trapped in a pattern of clashing interests.

It’s hard to say what the biggest generic “ecological” threat facing America is as there is much divide between environmental threats and conservation issues. Environmentalism has to do with toxins that affect humans and is much more anthropocentric, meaning it relates more directly to humankind. Conservation is more concerned with biological diversity: extinctions, loss of biodiversity and habitat, etc.

Recently staff writer Rory Hibbler received the honor of interviewing science-nature author David Quammen on his writings about the clashes between society and the environment. He argues that the climate should be our primary concern, due to its outreaching effects.

When habitats are broken up, populations become trapped and cannot relocate to adapt to climate change. He cites the frittilary butterflies in the mountaintops of Colorado as an example. They need a very specific habitat, and the particular wildflowers they consume are at risk due to encroaching snowmelts, thus endangering the butterfly population as well.

The butterflies are now trapped on top of the mountains of Colorado due to human development- a process called insularization. Scientifically, insularization is defined as the creation of islands of populations, and it’s a huge issue, although the general public typically remains unaware. Studies have shown that the more humans allow wildlife to fractionalize, the more interrupted ecosystems become. For example, the Three Gorges Dam in Sandouping, China created increased interspecific competition among rodent populations. Islands were created due to the disruption in habitat and certain species became trapped on differing islands. More dramatically, in his book Monitoring Ecological Change author Ian Spellerberg writes “the insularization…has resulted in species and population extinctions…insularization has both ecological and genetic implications and reduced variability has long been recognized as a feature of small and isolated populations.”

As Quammen stated it, this is one of America’s biggest conservation crises because “people can move, but habitats can’t.”

Once the need to preserve the earth has been established, the next issue is how to convince society of this. “The best way to conserve…is to mercantilise,” according to Quammen. While capitalism is grossly oversimplified in this question, will allowing people to harvest endangered or threatened species for profit work to benefit the survival of the species? The answer is, there is no answer. According to Quammen, there is no catch-all, one-stop solution. Every animal is different and while perhaps crocodile farms in Australia will preserve the Crocodylus porosus, it may not work as well for elusive Siberian Tigers of Russia.

Other incentives for conservation are “tricky and very important.” The “Muskrat Conundrum” is David Quammen’s term for the balancing act between human desires and wildlife conservation. There is a tension between human safety and ecological safety. Explained in its true detail in Quammen’s book Monsters of God, the impoverished (and often native) populations will remain preyed upon by dangerous predators so the rich can enjoy the benefit of knowing there are still lions, tigers, and bears in the world—as long as those predators aren’t in their backyards. Quammen says “we must have to deal with that reality.” The ethical fix here is to let the poor enjoy the benefits along with the strife of tigers in their village. Quammen cites ecotourism as an example of a way to “monetize these resources” and preserve social pressures along with ecological ones.

However, economics can only go so far. Another prong to this approach is by persuading inherent value to wild spaces left on this planet. Quammen believes that money isn’t the only way to convince populations to conserve our planet. Instead we also must “capture their imaginations.”

In order to conserve, people must ignite “aesthetic and intellectual” inspirations as well as be sensitive to economic needs. The poor and the rich must come together to share the burden and the benefits of coexisting on a planet of monsters.

Turning the situation around, there are also instances when the environment seriously impacts humans. One situation lies in one of modern science’s greatest puzzles: zoonotic diseases. David Quammen specifies with the term: Spillover, coincidentally this is also the name of one of his more recent books in which he discuses where terrifying diseases like Ebola and AIDS came from.

Where does #Ebola hide between outbreaks? Featured article @NatGeo @DavidQuammen http://t.co/0kUWTx41Zi pic.twitter.com/mSbCUxZbfg

— Dr. Thomas Gillespie (@BiodiversHealth) June 18, 2015

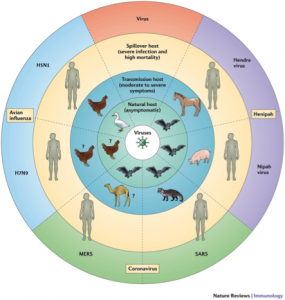

Essentially, many of the world’s most detrimental diseases came from animals that we share this planet with. The scary part is often times we have no idea how the disease spilled over to humans or what animal caused the spill. Take MERS for example, a subset of the Corona virus family. It’s a new virus that came from the Arabian Peninsula and it’s an especially alarming type because of its adaptability.

A man came home to South Korea from the Middle East and became incredibly ill. He was admitted to a hospital for respiratory distress and quickly it spread throughout the country. The question soon became, “where did this virus come from?”

Theories emerged, and fingers soon pointed to an animalistic explanation. These diseases are called zoonotic. They spread to humans via animal contact, dubbed the “reservoir host.” For SARS, the cousin of MERS, it is bats. But for many zoonotic diseases, such as Ebola, the reservoir host is a mystery. Lately Quammen’s work has been following scientists who are unraveling these mysteries.

Quammen explains, with each new disease that emerges we have two questions: where did it come from and how did it spillover to humans?

December 2013, a young boy in Guinea died unexpectedly. Soon so did his sister, mother, nurse, etc. There was one spillover from some sort of animal contact and suddenly 27,000 humans have died from Ebola. How did this boy get the disease? What gave it to him and how can we stop it?

Quammen’s advice for the last question is to “understand mechanisms of transmission and interrupt it.” Prodding further into this counsel, how can we interrupt when there are cultural barriers, ie the burial traditions of some African cultures?

“Respect those cultural practices and offer alternatives,” he said.

Compromise is key. Educate both sides of the spectrum: scientists and doctors trying to prevent the spread and indigenous cultures affected by the outbreak. It’s taken almost 40 years of research since Ebola’s discovery and we still don’t know what caused the start. Nonetheless, we can do our best to prevent its spread and the spread of so many other zoonotic killers.

– By Rory Hibbler