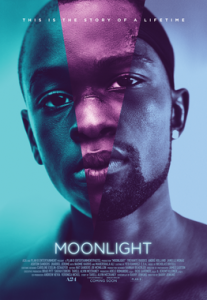

To try to simplify “Moonlight” into different talking points would be to destroy the magic that its director Barry Jenkins has created; it is not just a film about identity, drugs, mass incarceration, homosexuality, being black and male in America, motherhood, fatherhood, or anything as simple as making dinner. It is a film which portrays, in the combined beauty of its themes, life itself.

“Moonlight” is one of the few films where everything blends together perfectly without the aid of modern film gimmicks like CGI or the often sought after but poorly executed twist ending. It enters knowing its power and leaves knowing the strength of its vision on the audience. This profoundly unique vision culminates in one of the best endings in years, but also one of the riskiest. There is no final battle nor a typical call to action, just a simple conversation that seeks to portray to the audience a few simple ideas: This is reality. There are no do-overs. There are no true happy endings. And as such, we must rely on the only world known to exist, the world that our human connections’ form.

To lead us to this realization, Jenkins uses the life story of Chiron, which is separated into three sections, “Little,” “Chiron,” and “Black,” that refer to the lead character at a particular point in his life.

The film’s opening section, “Little,” sees Chiron (Alex R. Hibbert) as a boy, who is expectedly small in stature, but feels even smaller by the section’s namesake tag the neighborhood bullies give him. From the onset, we see Chiron running and trying to hide from his bullies in an abandoned apartment building, a place where he is eventually found by a local drug dealer Juan (played remarkably by Mahershala Ali). Here, the film breaks with the wicked drug-dealer/gangster stereotype that plagues so many films and television shows. Instead of using Chiron as a pawn in a drug empire, Juan looks to take care of him. He takes Chiron out to eat and then to meet his partner Teresa (Janelle Monáe). You truly feel, at this moment, that things are going to be fine for the boy; but that is a simplified vision, and if there is anything Moonlight seeks to tackle, it’s over-simplification.

While Juan sees hope in Chiron and, likely, even cares for the boy, Juan is the cause, in part, for the disintegration of Chiron’s family. Chiron’s father has been gone for some time, and his mother Paula (played by Naomi Harris, in what is the most underappreciated performance of the film) is Juan’s best customer. Thus, Juan is a helping hand by giving Chiron a place to stay or money in times of need, but his necessity is indubitably caused by the chaos he sells.

The film transitions into the second segment, “Chiron,” where we meet Chiron as a teenager, who is now dealing with more abject questions about his identity (both sexual and not). To the viewer, it is clear that the other males’ sexual bragging does not apply to Chiron, or even interest him. He seems to be more complicated than the “chest-pounding” bullies of his past and present; however, we do not know the extension of this complication, so we simplify this as a symptom of his past and current trauma. Yet because of this simplification, we miss the reality that even Chiron does not know who he is; has the question, we should ask, even entered his mind?

Regardless, Chiron (now played by Ashton Sanders) is a broken boy turning into a lost man. His past, as horrible as it was, seems preferable to the world he now inhabits. He has moved to one of Miami’s projects. His mother appears to be unemployed, and her drug use has driven her to moments of hysteria. He must now literally live off the “kindness of strangers.” In fact, he lives off exactly one stranger: his off-and-on friend Kevin (Jharrel Jerome). I note off-and-on because like fellow teenagers, Kevin has a cruel and violent streak that dominates the vision of their community’s masculine ideal. Yet, we can be sure that there is a loving connection between the two; however, we are not clear, if either party truly understands this connection. After all, Chiron at the very least does not understand himself.

In Chiron’s final incarnation, we meet “Black” (played with succulent beauty by Trevante Rhodes). Chiron, the boy, has disappeared; but as we can see in one scene, the moonlight coming from his Atlanta apartment window glows on his body to reveal his hidden pain stemming from his past trauma. The pain is undoubtedly present; he has just learned to hide it better. Unlike the previous section, Kevin (played by André Holland) is now the person reaching out to Chiron. For the first time, we see Kevin as lost as Chiron. These two men, who grew-up together and have a deep affection for each other, look into each other’s eyes and truly see one another. This is never stated, of course; but like everything else in the film, it is what is not stated that has the most power.

“Moonlight” could have easily felt broken by falling into an episodic style. Yet, like any well-constructed film that takes a similar approach (“The Last of Us,” “Boyhood,” and “The Shining” to name a few), “Moonlight” combines stories in a perfectly believable manner. This is due in part to the performances of the three lead actors (Hibbert, Sanders, and Rhodes), as well as the expert directing of Jenkins, who was able to create a fluid and cohesive narrative – one that borrows heavily from the literary work of Richard Wright’s masterpiece “Native Son” and James Baldwin’s tour de force “Go Tell It on the Mountain.”

It is Jenkins’ masterful directing that makes Chiron the character that he is; without it, Chiron would not have felt as real. In truth, “Moonlight,” from its characters, its sets, and its soundtrack, all work to make this world truly real. Without out the perfection of each component, the film would have been a failed vision, but “Moonlight” succeeds. In fact, it does more than succeed – it lives, breathes even. It is the strength of that vision that has catapulted “Moonlight” to win the Golden Globe for Best Drama Picture, and for it to be nominated for eight Oscars, including Best Picture. “Moonlight” did all this by being itself; thus when viewing “Moonlight,” do it with the expectation of just another film, but you will most certainly leave knowing the true understated price of life.