By: Michael Ingram

By: Michael Ingram

China to the average layperson appears monolithic. Their political system is notoriously opaque with virtually all prominent decisions occurring behind closed doors. Their language is overwhelmingly daunting with its vast and complicated set of pictograms and tones. Their culture is both long and proud, but in the West, it often seems more mythical than historical. All of these factors combine to present serious obstacles to wrapping one’s head around China. But one thing that is often passed over is that China is a nation of people as anywhere else. These people have deep seeded values and convictions, and with China on the rise, it becomes more important every day for political scientists, politicians, analysts, and American citizens to have an accurate picture of what it means to be Chinese. Fortunately, I got to go behind the scenes and converse with actual Chinese foreign policy students and their esteemed professor (in the interest of all parties involved both names of the participants and the institution must be kept confidential). What I discovered was that the mythos of China falsely obscures the similarities they share with us, and that the worldviews held by the Chinese may ultimately conflict with our own in the realm of foreign policy.

Our classroom was defined only by its emerald chalkboard, austere egg-shell white walls, and drab yellow curtains. Other than that, the most notable feature was the oppressive stuffiness from the midday heat. From the street, one would have little chance at guessing the nondescript, concrete building was one of the most prestigious universities in Beijing. My brief stint in Chinese demonstrated that advancement often comes at the expense of aesthetics. During my time with the Chinese undergraduates, who are essentially guaranteed to hold integral government positions in the near future, we came no closer to solving the issues that will continue to strain Sino-American relations for decades to come. However, what I did gain was a nearly uncensored insight into international relations from a Chinese perspective, and all the differences that accompany such a worldview.

A subtle, but profound aspect of the entire interaction was that it took place completely in English. We were in a Chinese classroom, with Chinese students, a lauded Chinese professor, in the Chinese capital, in a prestigious Chinese university, and every single word of the conversation was in English. It was not just the fact that none of us Americans knew Chinese, but all of the Chinese students could speak clearly and confidently in our native tongue. What became evident was that while Chinese assumed their ascent to superpower status presaged, nothing could quite show the power of the United States as well as the ubiquity of the English language even on the home turf of the rising power. It made for a peculiar dynamic, but the one thing that was made clear was that America’s presence was an ever-present variable that loomed large in the confounding equation that is East Asia. It also showed what lengths the Chinese would go to be competitive.

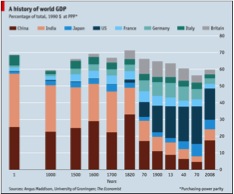

Chinese competitiveness and desire for growth is underscored by a deep sense of patriotism, which was fervent in all our Chinese counterparts. Remarkably, it struck me as comparable in tone to our own patriotism. In America, one can easily get the impression that we think ourselves above the international system and that it is our way or the highway. Couple this perceived infallibility with economic dominance on world stage, and domestically, Americans hold a sense of having an unassailable position at the top of the totem pole, while internationally, we are viewed as bending the rules in our own favor. China would concur with the second statement, but China could easily replace America in the previous sentence. For the majority of the last two thousand years, China has maintained the world’s largest economy by GDP. They are no strangers to the top of the world order, and their patriotism reflects their confidence. Like us, they simply want what is best for their country, whether that be perceived or actual. I have little place to judge that as an American citizen. But while our national desires are similarly grand, there remains one stark difference. In America, for all our fawning for grandeur, we can still take a step back and examine the course of our actions. It may not be immediate, it may not even be for years after our mistakes, but we have the ability to question ourselves, our leaders, and our actions. China shares our sense of national determination, but without the hindrance of open debate and discussion. What this means for the future is uncertain. It offers their authoritarian government free reign, but it could also mean turning a blind eye to a reality, for example, where decades of sustained, double digit growth is a reckless fantasy rather than a preordained fact.

Chinese competitiveness and desire for growth is underscored by a deep sense of patriotism, which was fervent in all our Chinese counterparts. Remarkably, it struck me as comparable in tone to our own patriotism. In America, one can easily get the impression that we think ourselves above the international system and that it is our way or the highway. Couple this perceived infallibility with economic dominance on world stage, and domestically, Americans hold a sense of having an unassailable position at the top of the totem pole, while internationally, we are viewed as bending the rules in our own favor. China would concur with the second statement, but China could easily replace America in the previous sentence. For the majority of the last two thousand years, China has maintained the world’s largest economy by GDP. They are no strangers to the top of the world order, and their patriotism reflects their confidence. Like us, they simply want what is best for their country, whether that be perceived or actual. I have little place to judge that as an American citizen. But while our national desires are similarly grand, there remains one stark difference. In America, for all our fawning for grandeur, we can still take a step back and examine the course of our actions. It may not be immediate, it may not even be for years after our mistakes, but we have the ability to question ourselves, our leaders, and our actions. China shares our sense of national determination, but without the hindrance of open debate and discussion. What this means for the future is uncertain. It offers their authoritarian government free reign, but it could also mean turning a blind eye to a reality, for example, where decades of sustained, double digit growth is a reckless fantasy rather than a preordained fact.

A second major takeaway from a Chinese patriotism that so closely mirrors our own in America is that taking no for an answer is not acceptable. The Chinese do not understand why America would stand in the way of solving territorial disputes in the favor of China. Especially concerning the Senkaku Islands (known as Diayou on the Chinese mainland), they feel as if the U.S. is unfairly supporting Japan, a key military and political ally. The Senkaku dispute and a host of other contested islands have contentious histories dating back to the 19th century or beyond, but the discovery of oil reserves, coupled with control of fishing grounds and shipping lanes make these hot zones even more critical now. But this mindset is understandable. America does not take kindly to the rest of the world trying to reign in our power. Just look at America’s human rights rhetoric compared to our actual compliance with organizations like the International Criminal Court. As the global hegemon, however, double standards just come with the territory. As was clear during the Cold War, the mutual exclusivity of international supremacy often leads to tension and dangerous misunderstandings. The sense of patriotism in China means that unless the goals of America completely overlap, they will have no intention of curbing their ambitions.

Yet while the differences in our national identities and goals were stark, differences began to evaporate on an individual level. The students were as avid consumers of American culture as us American students. They watched Big Bang Theory and How I Met Your Mother (in this they might be more American than me) and listened to American music. All these opportunities provided by China’s lax interpretation or rather rejection of American copyright laws. This had an unintended effect on exposing the Chinese to the fruits of a free society. The Chinese leadership would ironically be allowing the spread of American ideals under the guise of subverting America’s iron grip on international trade rules. Their relatively free access to culture was just one of the many contradictions that seemed to define China.

[At this point, I will address three of the overriding concepts from my discussions with the Chinese students. No names or specific quotes will be used out of sensitivity to both institutions involved.]

…And Now for Something Completely Different

America’s pivot to the Pacific is quickly becoming the main focus for our political-military establishment. Gone are the days when the Middle East absorbed such a disproportionate amount of America’s collective consciousness and resources. But what drives this pivot? It is a move to develop a bulwark against Chinese aggression or something more benign? This was the question our Chinese friends asked.

The Chinese professor started simply enough by using the formation of NATO to compare the motivations for the current pivot. NATO and the corresponding U.S. foreign policy initiatives in post-WWII Europe were driven by a desire to spread democracy. We wanted to keep the Iron Curtain from creeping further into West Europe. But while NATO expansion saw a large military buildup in Europe, America was not there to expressly keep European powers in line (Russia notwithstanding). However, from a Chinese perspective, the recent pivot seems to be based not on spreading the norms America holds so dear, but rather a strategic move of containment in a game of power politics. This is most worrying to China as it is perceived as substituting military might in the place of communication and diplomatic measures.

Our Chinese counterparts wanted to know if the pivot was the result of realist logic. Realism for our non-IR readers can be defined by Dmitry Kostyukov as three main tenets: “1) power calculations as the metric of importance in understanding state behavior; 2) willingness to discard policies that are not advancing one’s interests; and 3) the willingness to use one’s advantages to threaten and enforce preferences on other states.” This is a question that does not have an easy to answer. Obama campaigned on a foreign policy paradigm that differed from those that dominated throughout the Cold War. However, once in office, idealism often gives way to the gritty practicality of navigating the anarchy of the international wilds. Yet realist scholars would balk at the idea that Obama’s agenda is driven by realist logic over a liberal logic that more reflects his ideology. Despite America’s lack of a singular guiding light, the Chinese immediately knew their theory of choice.

The Chinese had their theoretical foundations in the paradigm of Constructivism. This theory, intelligently surmised by Alexander Wendt as “anarchy is what states make of it”, says in a nutshell that ideas and norms are the main driving force in the international system and that these can change over time, thus changing the system. While I was surprised that they put so much stock in Constructivism, it actually makes sense if you look at China’s track record in institutions and interactions on the world stage. While the Chinese stated that they were a status quo power, one that benefitted immensely under the current U.S. led system, their emphasis on Constructivism begged the question of what norms do they want to change? The answer is more than they let on. From international financial institutions like the IMF, to international organizations like ASEAN or the UN, China seeks to increase their leadership capacities. What emerges is a particularly clever plan to gradually raise their institutional prowess and change the rules of these organizations accordingly. Yes, they profit under the current system, but it seemed awfully humble of them to limit their desires to transform the international system in proportion to their power and influence. So when they said they were explicitly not revisionist, the thought that went through my head was “not yet, at least”. While heralding Constructivism is not proof positive of a revisionist agenda, it does beg the question of what norms exactly does China wants to spread.

The Many Faces of Sovereignty

In 1648, the bedrock of the current international system was laid. The modern idea of a nation-state was born out of the Treaty of Westphalia. The most profound result of the treaty was the inception of Westphalian sovereignty. This sovereignty, which differed from other traditional notions of sovereignty that championed fixed territorial boundaries, called for states to avoid becoming involved in the internal affairs of other states. This concept gave the leadership of states priority in controlling and molding their populations. While this was instrumental in allowing the proliferation of independent and self-governing states, recent history has shown that sovereignty is often a much more complicated issue.

From puppet regimes to satellite states, from forced democratization and internationally-enforced peacekeeping missions, the sovereignty of modern states depends more on perspective than a codified definition. America tends to elevate sovereignty at home as the element that allowed us freedom from oppression, but internationally, sovereignty is quickly forgotten if it infringes on America’s national interests. China is becoming increasingly aware of the opportunity to use America’s own rhetoric on sovereignty to solidify its position in the international order. One thought-provoking idea brought up by one of the Chinese scholars was why America could be revisionist in the Middle East (ignoring sovereignty of Saddam’s regime in Iraq in order to spread democracy), but China could not be revisionist in East Asia (concerning their territorial disputes)?

In fact, China’s Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence begins with a “mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity.” This means that Western or Eastern, large or small, rich or poor, totalitarian or democratic, each states has the unequivocal power to run its state as it sees fit. While this would seem admirable, especially in light of America’s overseas adventures in democratization, China’s desire to promote sovereignty could also be viewed as a double-edged sword. It does this by using sovereignty as a cover for quelling its citizens at home. China essentially states that it will turn a blind eye to the negative aspects of other governments in exchange for them not condemning the authoritarian actions perpetrated by the Chinese government on their own turf.

This model of turning a blind eye offers protection to the worst of governments. Democracy is still not a universal concept, and the Chinese definition of sovereignty provides support for other autocracies in a world where political oppression is increasingly becoming a public relations nightmare. China is simply playing the system to their advantage. With a vacuum of alternative political ideologies, China views their neutral stance on sovereignty as a tool to curry favor with nations disillusioned with the perceived hypocrisy of American foreign policy.

The Blinding Red Sun

So where do American and Chinese strategic interests coincide? The totality of East Asia would be an obvious answer, but insufficient for future peace. America has long had a foothold in the region with bases dotted throughout the Pacific in places like Guam, South Korea, and Okinawa. But it is America’s presence in China’s immediate vicinity that threatens to give teeth to their “peaceful rise.” Similarly, Obama’s recent Pacific pivot sends a message of posturing rather than reassurance. Peaceful coexistence in a region neither is willing to forfeit requires an impetus in which cooperation trumps self-interest and conflict for both parties.

One idea that quickly surfaced was joint military exercises. Already the American and Chinese navies are conducting counter-piracy drills in the Gulf of Aden. These joint training sessions can foster trust between two nations who are growingly increasingly skeptical of one another. Further still, counterterrorism may be a potential solution as Islamic fundamentalism grows in violence among the Uighur populations of Western China. Terrorists have their eyes set on both states; but like piracy, terrorism is more a defuse enemy than the Soviet Union was back in the 1970’s and 1980’s.

Now the USSR was a strategic rival both the United States and China could hang their hats on. Few people realize that during the Cold War between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. there was a concurrent arms race occurring between China and the Soviet Union. Ideological divergences from both states lead to a souring of relations that would not be normalized until 1989. In fact, the Sino-Soviet split was capitalized on by America as a way to increase cooperation, namely through the opening of the Chinese economy to American trade. While terrorism might not have the same rallying effect as the “Evil Empire,” the Chinese students definitely had an idea of where would be a good place to start. What was surprising was when we asked the Chinese students to vote, North Korea was a distant second place. One could almost say it was the elephant in the room.

It makes sense why China would still harbor such resentment and fear of Japan after well past the half-century mark. Japan’s bloody attempts at colonization robbed several Chinese generations of countless lives. While Sino-Japanese relations continued to flounder after the dismantling of the Japanese military state due to America’s increased military presence there, Japan will continue be etched in the Chinese conscious as a potential threat due to its imperialistic past. America at least spent WWII in the trenches with China and not against them. One particular example demonstrates the currency of anti-Japanese sentiment in China. The Senkaku dispute enflamed massive demonstrations across China; these events were made even more curious by the fact that there is no such thing as freedom of assembly in China. Authorities were more than happy to let Japan be the object of indignation and a distraction from domestic economic issues, only opting to remove protestors after the protests turned violent. Conflict between China and Japan has been a reality for centuries. Yet, the root of Chinese antipathy towards Japan lies in the waning influence of Communism being replaced by anti-Japanese nationalism, something the Communist party is willing and able to exploit.

Perhaps the best way to understand how the U.S. and China could come to terms would be to apply the NATO analogy from earlier to the current situation in East Asia, which is exactly what the roundtable did. Whereas NATO was prominent in post-WWII Europe to keep the U.S.S.R. out, the U.S. in, and Germany down, perhaps America’s presence in East Asia could serve to keep the U.S. in, China peaceful, and Japan down. In this context “down” sounds like a negative term, but it would be better interpreted to mean keeping Japan’s militaristic undercurrents from bubbling to the surface. One need not forget that Japan is both an American ally and a mature liberal democracy, but the ghosts of the past still hold considerable sway. Japan’s current Prime Minister Shinzo Abe knows how to use provocation as a means to an end in the domestic politics of his nation. He has been simultaneously unabashed at hinting at the darker legacies of Japan’s past, while also reigniting the debate over the reviving the Japanese military. His actions and words have harkened back to the days of Imperial Japan, and understandably it raises China’s anxiety. Instead, America and China should cooperate on cooling down the hothead Abe. In the near future, a remilitarized, nationalistic Japan scares China much more than America. In order to maintain our place at the table of East Asia and the Pacific, we have incentive to keep the horrors of WWII from reemerging in the present.

Conclusion

When I stepped into that Beijing classroom, I did not expect how frank our discussion would be, or for that matter, where it would take us. I look at the Chinese in a new light, mainly because before their actions and thoughts had been obscured by the darkness of secrecy. While I have begun the sizeable task of wrapping my head around Chinese foreign policy, it is still immediately clear that challenges lay ahead. Firstly, America needs to integrate the People’s Republic of China into the current international order, one predicated on democracy and human rights, before they can supplant the current order for one that reinforces China’s ideology. America needs to recognize China for what it is, a rising power, and allow it to play a responsible role in the future of the world. China does not want to be contained, because the Chinese feel they have as much right as Americans to use their influence on the world stage. Yet, issues like Taiwan and a large number of other territorial disputes, coupled with China’s single-party authoritarian government, cannot remove the potential for conflict from the equation. Above all, the revival of nationalism in both China and Japan could lead to deadly future consequences. Thankfully, my time with the Chinese students showed me that the educated youth are more interested in learning and cooperation, but there is no guarantee that extends to the upper echelons of Chinese leadership. Sino-American relations are a complex beast, but our collective futures depend upon peaceful coexistence. I hope that, despite our vast differences, we can push forward through mutual understanding, so that our interests may eventually converge and so another Cold War (or World War) is averted entirely.