By: Park MacDougald

By: Park MacDougald

By now, many of the more wonkishly inclined among us will have heard the names Reinhart and Rogoff bandied about the political blogosphere as an example of empirical analysis gone wrong. To make a long story short, the Harvard economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff authored an influential paper in 2010 suggesting a significant correlation between government debt levels at or exceeding 90 percent of GDP and slow or negative economic growth. A recently released study, however, by economists from Amherst, revealed a litany of errors in the original paper. Some of these mistakes were embarrassing – like an obvious spreadsheet error that failed to include statistics from all the countries in the study – but not crucial to the findings; others, like bizarrely weighted statistical categories, were less cringe-inducing but more integral to the study’s results.

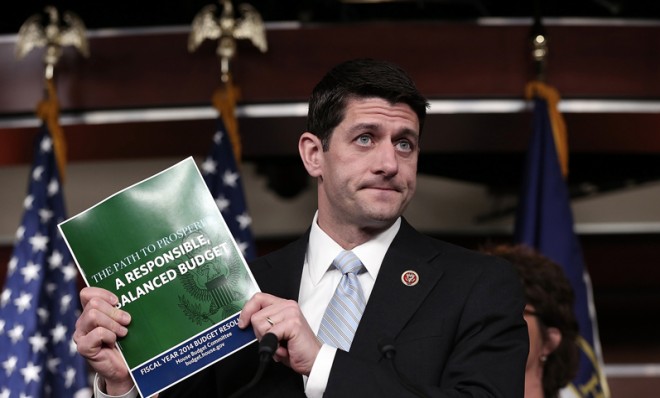

The impact of the Amherst paper has been tremendous, at least among the talking and blogging heads. Reinhart-Rogoff was frequently cited by proponents of fiscal austerity, and was, amazingly enough, the only piece of evidence on the consequences of high public debt for economic growth cited by Paul Ryan in his infamous “Path to Prosperity.” Reinhart and Rogoff, once the divine monarchs of the economic public policy debate, now stand as Citizens Louis Capet before the guillotine of American liberal punditry, maintaining that the errors do not significantly challenge the study’s findings.

Reports of the death of austerity, however, have been greatly exaggerated. Whereas the ‘debunking’ of the purported “intellectual bulwark of the austerity movement” has proved to be Christmas come early for the snappy center-left commentariat, political positions have moved remarkably little. For those on the left, Reinhart-Rogoff was never convincing in the first place. From the beginning, Keynesian-inclined economists had acknowledged the correlation between government debt and slow growth while disputing the causation, arguing that slow growth caused governments to accumulate debt, rather than the other way around. On the right, austerity remains common sense – too much debt, spend less – a formulation with a truthiness factor that a single paper from an economics department already considered by conservatives to be an untrustworthy bastion of neo-Marxist quackery is unlikely to change. Perhaps, somewhere floating in the near-mythical ether of undecided voters that populate the margins of our political discourse, some self-styled Very Serious People have changed their minds based on new information, but there has certainly been no tectonic re-alignment of the discussion around austerity.

This, however, should not be so surprising. The rise of “wonks” to a privileged position within the American chattering classes has given rise to a certain myth about the way politics functions and operates. These wonks – bloggers and commentators like the Washington Post’s Ezra Klein or Slate’s Matt Yglesias – present a vision of politics that is in essence apolitical, one in which hard-nosed bloggers and journalists, wielding their Excel spreadsheets and empirical analyses like Narsil, can slay the Dark Lord of irrational policymaking through the calm explanation of objective facts. In an age of polarized politics and dysfunctional government, this vision is appealing. It is, however, only a vision.

In his essay “Just the Facts” in the most recent edition of The New Inquiry, Jesse Spafford compares wonks of the Klein-Yglesias variety to conspiracy theorists such as Alex Jones. Of course, to most of us, the former are respectable journalists while the latter is a loud-mouthed crank – what Spafford does is to demonstrate why “the facts” can ultimately never overcome ideology. If you attempt to demonstrate to an InfoWarrior (a follower of Alex Jones’ website InfoWars) that his beliefs are empirically and demonstrably wrong, you run into what is known in scientific circles as the Duhem-Quine problem, or the impossibility of falsifying any single hypothesis in isolation because of how that hypothesis ultimately rests on the assumption that other hypotheses are correct. For instance, a scientific study that disproves the claims of a conspiracy theorist can easily be dismissed by conspiracy theorists, because it assumes that the scientists involved in the study were not paid off by members of the New World Order, or were not ideologically motivated to falsify their results, etc. Unless all journalists and readers reproduce the results of every study themselves, their understanding will ultimately rest on an appeal to authority. If they do not trust this authority (see: talk radio paranoia over government unemployment statistics), there is no reason to believe they will, or even should trust the results.

Moreover, politics, is a contest over power, resources, and their distribution, and as such is inherently ideological and value-based. There is no objectively neutral position that left and right can agree on if left and right have radically different goals. Ezra Klein will never be able to successfully mediate between a socialist and a libertarian – no degree of economic efficiency will convince one that material inequality is morally acceptable, and no degree of inequality will convince the other that government redistribution is morally acceptable. Psychology tells us that our political beliefs stem from our pre-existing system of morality. That is, we decide what we believe is right (or our brain chemistry decides for us), and then tailor our politics to suit those beliefs. House Republicans are often ridiculed for refusing to compromise, but, ultimately, the joke is on those who expect them to. They know what they believe is right and wrong and what their constituencies want, and they do everything within their legal power to assert or protect their vision of a good society. Others may disagree with their vision, but the response should be to forcefully articulate a vision of their own, rather than to laugh at those who do for being a bit gauche, because, at the end of the day, they are the ones doing politics right.