By: Darrian Stacy

Source: Micah Baldwin

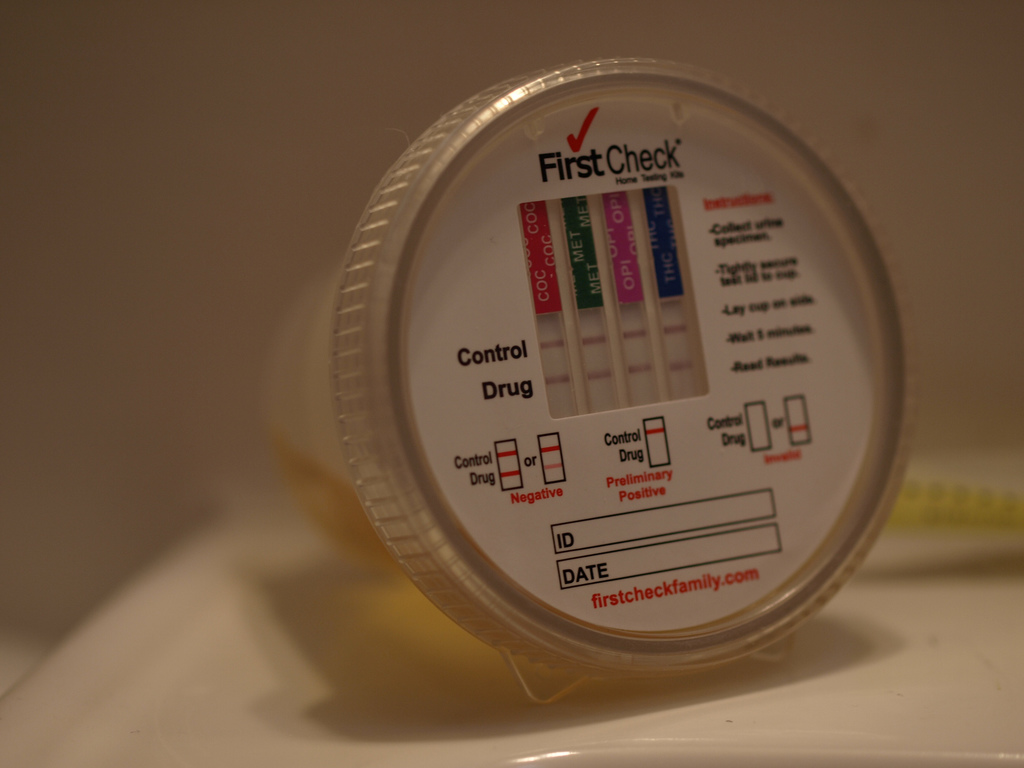

According to some Georgia legislators, the time has come to once again examine what they perceive as a major waste of taxpayer money: no, not a new Braves Stadium but the impoverished individuals receiving government assistance that may also be using drugs. At the beginning of March, the Georgia House passed H.B. 772 which seeks to replace H.B. 861, a law signed by Gov. Deal in 2012 that would require applicants to undergo drug testing before receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) benefits from the state. If enacted, this new, toned-down bill would change the requirements for receiving benefits so that individuals would only be required to undergo drug testing if caseworkers suspected them of using drugs.

This new compromise is a response to the inadequacy of the previous legislation, based on a Florida law that contained similar language. That’s right, “based,” (as in past tense) because both laws were axed after a federal judge ruled the Florida version as unconstitutional due to its violation of the Fourth Amendment’s protection from unreasonable searches. In her decision, Federal Judge Mary Scriven declared that “there is no set of circumstances under which the warrantless, suspicionless drug testing at issue in th[e] case could be constitutionally applied.”

Judge Scriven rendered her verdict on the last day of 2013, but the issue has not subsided in the aftermath of the ruling. A mere 17 days after the court ruling (four days after the legislative session began), H.B. 772 began the motions of going through the legislative process. The legislature’s answer in the face of a federal court’s invalidation is to rework the law around one word of the decision, “suspicionless.” If passed the new legislation would empower bureaucrats (untrained in detecting substance abuse) to judge when to make unfortunate individuals pee in a cup.

While this incarnation of the bill may be slightly nuanced, the same can’t be said for the arguments in its support. As the reasoning goes, individuals who need government assistance shouldn’t be using drugs, thus this legislation will save money by ensuring taxpayers aren’t subsidizing “immoral” activities.

When signing the original bill into law back in 2012, Governor Deal cited the decrease in Florida’s welfare benefit applicant pool by 48 percent (thereby saving the state $1.8 million) as evidence of why the Georgia’s emulated law was a good idea. It turns out, however, that the reported savings did not actually exist. According to Florida’s Department of Children and Families, the state’s number of applications for assistance had already been in consistent decline, and the decrease that Florida witnessed was actually projected before the law existed. In fact, many estimate (including some Georgia lawmakers) that while active, the law cost the state of Florida more than $40,000 instead of saving money given the number of reimbursements the state had to pay out to those who tested negative for drug use.

Of course, even if laws of this type cost taxpayers more money than they save, there is still the fundamental premise of the argument for why these laws are necessary: the moral imperative. Surely taxpayers do not want their money to go toward illicit ventures. Therefore, these laws are necessary to protect citizens. When observing other areas of governance in Georgia though, legislators’ concern for accountability seems disingenuous. While the legislature seeks to make the more underprivileged citizens of the state accountable, it has consistently ignored, underfunded, and undermined the state’s Ethics Commission, which is responsible for state government oversight. State officials seem perfectly content with ignoring well-documented research into waste and corruption in its own body in lieu of pursuing unconfirmed suspicions of abuses from the poor.

This brings us to the real crux of the issue. The driving forces behind Georgia’s initial law and its 2014 reincarnation aren’t just merely a concern for saving money or moral accountability. Back in 2011, Gov. Rick Scott summed up a third, more implicit argument, with the claim that “studies show that people that are on welfare are higher users of drugs than people not on welfare.” In a post “47 percent soundbite” world (which some speculate cost Mitt Romney the presidency back in 2012) this rationale that demonizes the poor isn’t emphasized much by politicians anymore. In a state with scarce reports of drug abuse by welfare recipients, however, the aforementioned assumption provides the context for a “problem” that wasn’t detectable before. There a number of issues with the notion though, most important being that it has been disproven. In the time that Florida’s drug testing law was active, a mere 2.6 percent of those tested yielded a positive result – “a rate more than three times lower than the 8.13 percent” of the state’s citizens who use illegal drugs.

As these arguments serve as the backdrop for the Georgia Legislature’s latest bill, it is important that the time is taken to once again critically examine them. A rushed (albeit scaled-back) bill that doesn’t address real issues of accountability, wastes taxpayer money, and effectively stereotypes the underprivileged makes for an ill-advised law. Yet, despite these logical faults, H.B. 772 continues its steady progression to becoming a law.