I should probably mention this before you read any further: major spoiler alert!

In the season 7 premiere of “The Walking Dead”, Jeffrey Dean Morgan’s cartoonish villain, Negan, bashed some heads in after a summer-long wait to see who met the business end of Lucille, Negan’s affectionately-named bat. If you haven’t watched (I repeat, SPOILER ALERT) or if you have somehow managed to evade spoilers from social media, then you probably don’t know that they chose to kill off comic relief Abraham (Michael Cudlitz), and fan-favorite since Season 1, Glenn (Steven Yeun).

“The Walking Dead” is no stranger to killing off characters – although despite their many claims that “no one is safe,” they mainly stick to killing off secondary characters, or characters who have gone way too long without any substantial character development (looking at you, Glenn). However, this particular habit of the show is to be expected; it is, after all, set in an unforgiving zombie apocalypse. Instead, the show’s most egregious error is that it has so much potential to create a visually-compelling commentary on what happens when law and order go out the window, and the dead roam the earth, and yet, it always shies away from that to get closer to its old friend: nihilism.

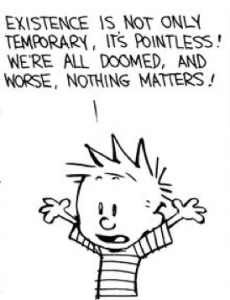

Post-apocalyptic dystopias must have some extent of nihilism, of course; one could assume that zombie apocalypses imagine this quite uniquely, with the dead coming back to eat you alive and civilization falling as a result. However, nihilism only works in modern television if there are challenges to that cynicism. Season 1 of “True Detective” did a great job of balancing Rust Cohle’s (Matthew McConaughey) nihilistic, pseudo-philosophy monologues with Marty Hart’s (Woody Harrelson) condemnation of Cohle’s life view, along with actual character and plot development that pushed against that nihilism. “The Walking Dead”, on the other hand, spends no time mourning, no time contemplating what it all means, and gives its audience no time to get attached to new characters or really think about the plot. No, “The Walking Dead” is not a show that respects its viewers that much; instead, it punishes them.

When it does, however, “The Walking Dead” tends to give those flimsy contemplations little screen-time and poorly-written dialogues. Take Morgan’s (Lennie James) season 6 ruminations on the meaning of life: “All life is precious,” he said over and over, only to be met with scorn and cynicism from the show’s protagonists. Indeed, the episode that started Morgan’s newfound compassion, “Here’s Not Here,” allows for some of this much-needed dialogue about what it all means. The episode is an exception, not a rule, as is evident once Morgan meets back up with the show’s protagonists, and is shut down. He is eventually proven wrong through a tedious set of violent events meant to prove to the audience that the show’s cynical protagonist (Rick Grimes) is always right about these things because he’s “seen stuff.”

When these things happen, I am reminded of the stellar first season of “The Walking Dead”, when it seemed like the show had the potential to do some world-building, character-building, even some plot-building. Yet, week after week and season after season we have seen none of that. Instead, we have seen Rick’s group follow the same plotline since season 2: try to find a safe place and have that place destroyed by an enemy (either dead or alive). If the enemy’s alive, then we get to see a potentially great villain reduced to a cartoonish, unentertaining plot device that only serves to exert some grotesque violent tendencies on the show’s group. Then, eventually, through only the power of the show’s subpar writing room, our protagonists prevail. Only, that victory does not last, because next season will see the same outcome. Maybe before that, “The Walking Dead” will produce one shining episode that manipulates the audience into thinking that “The Walking Dead” is finally growing up (Season 6’s “Here’s Not Here” and Season 4’s “The Grove”), but it will revert back to normal soon after.

This is why “The Walking Dead’s” nihilism doesn’t work: narratively, nothing is happening because as the show keeps telling us, nothing matters. And when nothing matters, if the same thing is going to keep happening again and again, why should the characters try to be good people or create relationships with each other? Why should they try to do anything other than survive? Watching characters do nothing except survive is boring after a while, but you wouldn’t get that if you look at the ratings. In fact, according to Entertainment Weekly, the season premiere earned 17 million viewers and an 8.4 rating among the coveted 18-49 age demographic. The only other scripted shows that come close to that are CBS’ “Big Bang Theory” and Fox’s “Empire”, each with a 3.5 rating.

Despite many critics’ unfavorable opinions on the premiere – Bryan Bishop and Nick Statt called it “torture porn masquerading as drama,” and Sam Adams said “its radically simplified moral universe is part of its appeal” and that the show is “truly ugly” – ratings continue to outshine other scripted primetime dramas by a long shot. I guess sex no longer sells quite as well as redundant nihilism and simplistic moralities.