By: Yuliya Bila

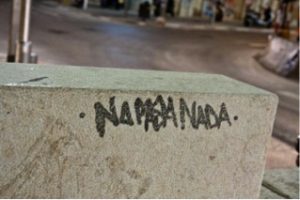

The Spanish national motto may as well be “no pasa nada.” That was one of the repeated phrases that I learned during my semester-long stay in Spain; it was used entirely too often and in all manner of contexts. When a classmate did not study and got a less-than-stellar grade on an exam? No pasa nada. When my friends and I had to walk to the train station because its website was out of order? No pasa nada. When I had to wait in line at a fast food restaurant for 30 minutes because the cashier was distracted by flirtations of a fellow employee? No pasa nada.

The phrase literally means “nothing is happening,” but carries the connotation of “whatever, it’s all good” and reveals an aspect of the laid-back Spanish attitude that both allures and frustrates outsiders. This carefree culture, focused on taking it easy and enjoying life’s treasures, seduces over 50 million overworked foreigners each year. This impressive number of individuals taking time off to travel or study abroad makes Spain the fourth most visited country in the world and contributes to the development of tourism as one of the country’s most lucrative industries.

Unfortunately, the elements of the Spanish mentality that attract college students and vacation-hungry families are not necessarily well suited to sustainably growing an economy of Spain’s proportions- especially when the same relaxed attitude often frustrates businessmen and investors, driving them to prefer the cost-efficiency of Eastern European labor markets and the precision and quality of Northern European companies. Mainstream Spain has been driven into a seemingly insuperable position; it finds itself dependent on relatively high earnings in order to afford the basic necessities (made much more costly upon adoption of the Euro in 2002). At the same time, the country’s labor force is unable to provide quite the same superior quality of products and services that the new globalized market expects of such a high-income society. This basic competitiveness deficit, left over from the isolationist days of Dictator Francisco Franco, combined with extravagantly inefficient spending during plentiful years and the recent global decrease in demand for tourism have all left Spain where it is today- battling staggering debts and unemployment levels rarely registered in the developed world.

Spain’s striking economic situation during the spring of 2012 prompted me to do a bit of research about how the issues are perceived by different groups. To my surprise, some Spanish university students, when interviewed about the 51% youth unemployment rate, said “the situation is unfortunate, but no pasa nada.” Spain’s conservative government does not share this relaxed attitude. Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy and the People’s Party have been frantically trying any and all measures to starve the country into industrial superpower shape along the likes of Germany. Their austerity measures and labor market reforms are aimed at trimming government spending on social services and promoting investment. The government has even gone so far as to solicit a $125 billion bank bailout from the Eurozone- becoming the fourth European country, after Ireland, Greece and Portugal, to take such measures since the beginning of the current economic crisis.

What Rajoy and the People’s Party do not realize is that the only way to foster real change is to tackle the mentality that makes Spain an inefficient investment regardless of how many public schools go months without heating, how many retirees see their pensions cut in half and how many European tax payers see their money diverted to save the ailing financial institutions of other sovereign states. Unfortunately, a complete cultural overhaul, including a smaller focus on high-cost, low-yield enterprises such as the hosting Formula 1 races and building exorbitant cultural centers like Valencia’s City of Arts and Sciences, could have a devastating impact on Spain’s national identity and thereby diminish the charm that attracts scores of tourists.

Finding the correct balance between the casual lifestyle and a more productive, results-driven work culture, however difficult, may be the only way for Spain to develop a healthier, more competitive economy and save the country from the kind of chaos that has plagued Greece in recent months. If, however the “no pasa nada” mentality cannot be channeled in the leisurely sphere of life and expunged from the professional world, Spain may as well throw in the towel and become accustomed to groveling in futility at the feet of its northern neighbors.