By Jessica Pasquarello

Activists often ask students at the University of Georgia (UGA) how many undocumented students attend the institution. Few students, if any, know the correct answer: none.

Since 2010, when the Georgia Board of Regents passed Policy 4.1.6, undocumented students have been barred from attending all of the state’s top (“selective”) public universities. That means that even for undocumented students that have lived in Georgia almost all of their lives, graduated as valedictorian of their respective high schools, and achieved perfect SAT scores, UGA, Georgia Tech, and Georgia College and State University (GCSU) cannot consider their applications.

The fact that these institutions are forced to deny entry to qualified students is baffling enough, but the plight of undocumented students in Georgia does not end there. Should undocumented individuals seek to continue their education at any other public institution of higher education in Georgia – including community colleges – they are not eligible for in-state tuition and thus are required to pay either out-of-state or international student tuition rates, which are typically three times higher. This is the result of the Georgia Board of Regents Policy 4.3.4, which was also codified by the Georgia legislature in 2008 with S.B. 492.

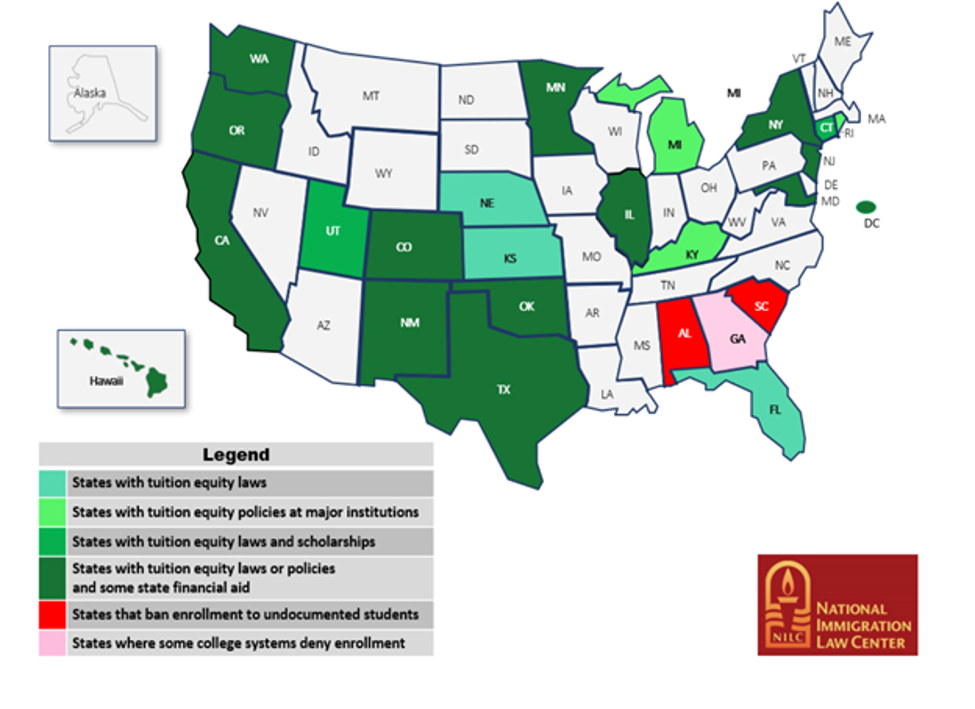

Yet Georgia’s policies are far from the norm, even in the South. Twenty-three states have extended in-state tuition benefits to undocumented students, and Georgia is one of only three states (along with Alabama and South Carolina) to completely ban undocumented students from public institutions. Georgia is also the only state in the nation that punishes (as of 2017, with the legislature’s passage of H.B. 37) private universities that choose to serve as a sanctuaries for undocumented students.

Approximately 400,000 undocumented immigrants currently live in Georgia, 59,000 of whom are of college age. Although many of these individuals have lived in the state for decades and actively contribute to its economy (Georgia’s DACA recipients alone pay about $61 million in state and local taxes), the state places every possible obstacle in their path to hinder their education, and thus, career and success. Paradoxically, these policies appear to harm not only undocumented students, but the state itself.

Consequences of Policy

By 2020, an estimated 65% of U.S. jobs will require some form of formal education beyond high school, and most states have decided that it is in their best interests to develop a well-educated (often bilingual) workforce by extending educational opportunities to undocumented individuals. By not prioritizing this, Georgia is considered an “outlier.” Considering that Georgia also ranks in the bottom one-third of states in terms of adult population with an associate’s degree or higher, one would think that the state would be eager to increase the number of college-educated participants in its labor force.

However, some analysts consider these policies in terms of past, rather than future investments. All states must provide undocumented students free access to public elementary, middle, and high schools (see the 1982 Supreme Court case, Plyer v. Doe), and, on average, this education costs the state of Georgia about $110,000 per child. Why is the state preventing itself from receiving its full return on investment by not allowing students to continue studying beyond high school and reach their full potential?

Moreover, given the high costs (and outright bans) that prevent many undocumented students from furthering their education in Georgia, many of the state’s top students decide to seek scholarships at universities elsewhere, thereby creating a “brain drain” in Georgia, since many of these highly capable individuals do not return home after college. In this way, other states are able to capitalize on Georgia’s initial educational investment in these individuals, in terms of their pre-college education.

On the other hand, some undocumented students may not see the benefit of finishing high school knowing that attending college in Georgia is nearly impossible for them; why run a race that you know you cannot win? By promoting this mindset, Georgia is further decreasing its human capital and its probability of having a well-educated workforce. However, just by changing its laws related to in-state tuition, Georgia could reduce high school dropout rates among undocumented students by approximately 27%. This is particularly important for undocumented girls, who may feel pressure to marry young in light of diminished chances of personal educational success.

In addition, Georgia’s current stance on higher education further traps many undocumented families in a cycle of intergenerational poverty while simultaneously causing the state to lose revenue. Attaining a degree can cause an increase in annual earnings of up to 391%, as well as a 56% decrease in unemployment rates. While allowing undocumented people access to college would certainly enhance their families’ financial stability, it would also generate economic growth, as individuals with either an associate’s or bachelor’s degree typically pay up to an additional $2,268 per year in state and local taxes. Thus, the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute estimates that current laws are costing the state about $10 million annually in lost tax revenue.

Aside from economic issues, Georgia’s policy also raises moral concerns. Article 26 of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “Everyone has the right to education… and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit.” Complementing this, the Human Rights Committee, a body of the United Nations, has formally stated that “There shall be no discrimination between aliens and citizens in the application of these rights.” As a result, some Georgians argue that the state’s laws relating to undocumented students violate international human rights law.

What Can Be Done?

On the ground, many grassroots organizations in Georgia already work with undocumented students to help them further their education. For example, u-Lead, in Athens, tutors undocumented students, helps them prepare for their SATs/ACTs and college applications, and connects them to scholarship opportunities, often in other states. Meanwhile, the “underground” Freedom University, in Atlanta, offers free college-level courses to undocumented students while also pushing for legal change and organizing protests.

But will there ever be a change in policy? Quite possibly. In 2016, three DACA recipients filed a federal lawsuit in an attempt to challenge the state’s ban on attendance at the top universities, and although their claim was rejected in court, it did bring national attention to the issue.

Consequently, any changes would have to come either from the Georgia General Assembly or the Board of Regents. Much of the discussion centers around the definition of “lawfully present,” the requirements for residency and thus, in-state tuition eligibility (typically other states have based it on attendance at and/or graduation from an in-state high school), and whether higher education is a “public benefit” to which undocumented immigrants have access.

For those who claim that providing undocumented immigrants access to college is unconstitutional, the counterargument is simple. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) said in 2008 that “individual states must decide for themselves whether or not to admit illegal aliens into their public postsecondary institutions.” Therefore, should Georgia choose to extend educational opportunities to undocumented immigrants, it is within the state’s jurisdiction to do so. Moreover, when California’s bill granting undocumented students in-state tuition rates was challenged in the State’s Court, it was found to not be in violation of federal law.

Finally, one important question looms: is a bill that would reverse current policy politically feasible? The answer is ‘yes.’ Other traditionally conservative states, such as Texas, Kansas, and Utah, have already passed bills granting in-state tuition to undocumented students. Some states have even gone beyond just providing in-state tuition and allow undocumented students to receive state financial aid.

Perhaps it’s time for Georgia to catch up. Perhaps it’s time for Georgia to revoke the policies that have hurt undocumented students for the past decade. In the meantime, Georgia is only hurting itself.