In the weeks following Troy Davis’ execution, many Georgians and Americans were left reeling, wondering what arcane instruments of legal policy could have led an innocent man to be executed in America. The GPR’s in-depth analysis seeks to put legal facts ahead of the media’s hype and get to the heart of the story.

Not the exception, but the rule:

Benjamin Franklin once said “it is better that 100 guilty persons should escape than that one innocent person should suffer.” Clearly he wasn’t from Georgia. For the most part, disrespect of this maxim is manifested in lower-level cases involving indigent clients and public defense. But recently, the capital case of Troy Davis garnered attention from many advocates for so blatantly ignoring the standard of evidence and burden of proof in Georgia. Capital punishment is a difficult issue to legislate because of the flux in public concern. Though cases usually take 20 or more years between arrest and lethal injection, death row inmates rarely appear on regular citizens’ radars until a week or two before the defendant will be executed.

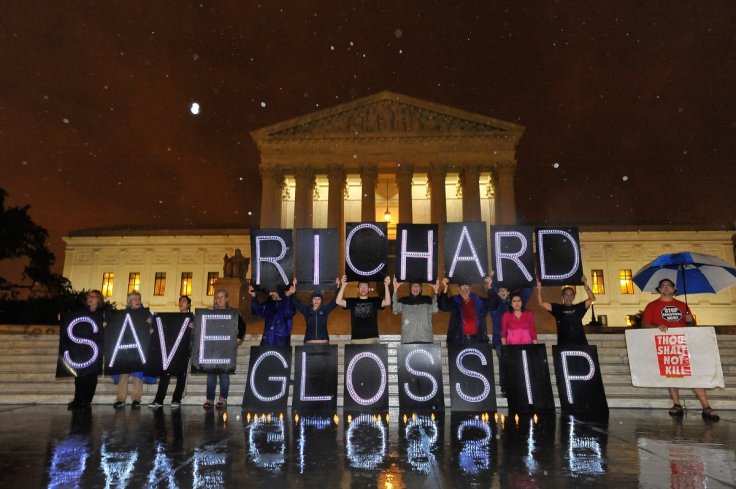

At that point, what appear in the media are the charges and how long the defendant has been on Death Row. Inevitably, the citizenry divides—those for capital punishment say it’s about time, and those against capital punishment insist that every life is valuable. Whether the case ends in a stay or execution, the impassioned populace recedes when the case becomes boring again (or, obviously, is over). Remarkably, since the 1991 case State v. Davis, in which Troy Davis was convicted of shooting police officer Mark MacPhail and sentenced to death, even advocates of capital punishment question the legitimacy of his original trial, appeals, and post-conviction relief efforts.

In a system supposedly predicated on the mantra that a defendant is “innocent until proven guilty,” Davis worked backwards since his arrest in 1989. Unfortunately, Davis’ case is not a shocking exception but an appalling microcosm of Georgia’s legal path from arrest to execution. I argue that Davis’ case is unique because its injustice is obvious and sympathetic, not because it represents a substantial departure from Georgia’s legal process. In one of the most publicized capital cases in legal history, allegations of prejudice and discrimination have fueled the fire of protesters. Most cases don’t get this kind of attention; instead, they end in injustice without publicity because of the cumulative effect of hundreds of defunct policies—no specific one of which is enough to prove unconstitutionality.

In order to trace exactly what went wrong in Davis’ case, it is necessary to examine every rule of the legal game in addition to targeting the individual players. Many of his supporters insist that Davis died an innocent man, and that may be the case. But, the legal distinction is between guilty and not guilty, and the legal standard is that the prosecution must prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Given that standard, the most compelling question is why Davis continued to be legally guilty after the evidence did not support his conviction beyond a reasonable doubt.

Reconsideration

Had Davis’ case been tried in 2011, the jury probably would have ruled against conviction. Most inmates are on death row because of crimes they committed 20 years ago, when DNA testing didn’t exist and an eyewitness’ word was the most valuable testimony. Consider the original evidence presented to the jury; the crux of the prosecution was nine eyewitnesses who positively identified Troy Davis as the shooter. The police originally took statements from twenty witnesses, some of whom claimed that Davis confessed to them, and some of who claim to have seen the shooter. In the 2010 evidentiary hearing about Davis’ original trial, most of these witnesses gave a second statement.

This is not unique for eyewitness testimony—out of the first 239 DNA exonerations, 179 involved eyewitness misidentifications (The Innocence Project). In Davis’ case, there was no physical evidence to test. Though eyewitness identification can be an important element in a conviction, many factors cause witnesses to be unreliable. The human memory is easily altered, and there is no across-the-board policy within police departments that determines how eyewitness identifications are made. Particularly troubling is the line-up method. Harriet Murray, one of the eyewitnesses who ultimately testified against Davis, was not able to pick him out of a photographic line-up the night of the shooting, yet days later, she picked Troy out of a second lineup because of his “narrow face.”

Other prosecution witnesses admitted to having seen Davis on television before picking him out of a line-up. Antoine Williams told police he was only 60% sure about Davis being the shooter, but his testimony was still accepted. CNN reporter Gary Touchmont interviewed jurors and eyewitnesses from the original trial. Seven of the nine primary eyewitnesses have recanted their statements and offered a second sworn affidavit saying that they were mistaken or coerced by police. Moreover, one of the jurors who supported Davis’ conviction said that if she knew then what she knows now, she would not have agreed to convict him. Based on Georgia’s unanimity rule, it only takes one juror to disagree with a guilty verdict.

Representation

Although Davis’ case garnered enough attention to attract pro-bono attorneys in its later stages, Georgia remains the only state in the country that does not guarantee counsel for those in post-conviction habeas corpus proceedings. Though these cases are still intrinsically criminal, habeas corpus is actually a civil case through which the defendant sues the state based on unconstitutional imprisonment. As the Constitution does not guarantee counsel for civil cases, whether or not a death row inmate is by an attorney is a matter of money or luck. Notably, almost all of these inmates qualify as indigent defendants. Without non-profit legal groups and affiliated attorneys, defendants would be forced to represent themselves during a process that most attorneys do not even understand. Most of the time, this process includes filing a claim that during the original trial, judge, juror, or prosecutorial misconduct occurred. Alternatively, some argue that their appointed counsel was inadequate in assisting them, legally termed ineffective assistance of counsel (IAC). In Davis’ original trial, no public defender was appointed. His defense team consisted of three hired attorneys: Robert Barker of Kansas and two local attorneys, Robert E. Falligant, Jr. and Nancy Askew. When representing Davis, they had remarkably little experience. Askew’s litigation history shows that Davis’ is the only criminal justice case she’s handled. Also, neither Barker nor Falligant list criminal defense work on their profile. In his Motion for New Trial, Davis’ new attorney filed a complaint of ineffective assistance of counsel “for failing to object to certain evidence and charges, for not requesting certain jury charges, and for not recalling a witness for additional cross-examination.” Considering the shaky evidence introduced by the witnesses, had the attorneys adequately handled the prosecution’s evidence, Davis might not have been convicted. The second concerns the jury, made up of twelve of Davis’ “peers.” Georgia requires each juror to be vetted to create what’s known as a “death-qualified jury”, meaning that those who oppose the death penalty cannot serve as jurors in a capital case. This policy undermines the protective measure of a unanimous vote to sentence a defendant to death. As Justice Stevens remarked in the Kentucky case Baze v. Rees,

the process of obtaining a ‘death-qualified jury’ is really a procedure that has the purpose and effect of obtaining a jury that is biased in favor of conviction. The prosecutorial concern that death verdicts would rarely be returned by twelve randomly selected jurors should be viewed as objective evidence supporting the conclusion that the penalty is excessive.

In Davis’ case, multiple jurors were excused because they were not sure they supported capital punishment. Although the Supreme Court refuses to strike down this process of excluding jurors based on their political views, it does follow that excluding anti-death penalty individuals will include more death penalty supporters on capital juries.

Responsibility

Another policy specific to Georgia that biases the system against defendants is the clemency process. Appealing to the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles (GBPP) is a last resort that occurs after a defendant has exhausted every possible legal avenue. In capital cases, the clemency process is an immediate matter of life and death. In most death penalty states, one individual (e.g. the governor) has the authority to grant clemency. Although this appears to be less democratic than a board, granting authority to one person also increases the accountability applied to his or her decision. The GBPP elides checks and balances by partitioning decisions in complete secrecy. No hearing or evidentiary presentation before the GBPP has ever been recorded. There are no transcripts to read, and the GBPP makes no reports. Moreover, because the decision cannot be attributed to the governor, as it is in other states, the public has no one figure to influence. The judicial branch isolates itself from the public for a reason, so that judges can interpret the law rather than public opinion. In contrast, the executive and legislative branches should interpret public opinion—this is the check on the judiciary necessary for state and federal government.

Everyone has bias, and a system based on human discretion will never be perfect. In fact, the reason capital cases span decades is so that the system can self-correct before acting irreversibly. Ideally, each member of the judicial process has a commitment to justice—the witnesses, investigators, prosecutors, defense team, judges, and the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles. In Davis’ case, these groups did not hold each other accountable, and that is why he spent twenty years on death row and was ultimately executed. In Amy Bach’s examination of systemic legal failure, she insists that:

What these examples show, however, is that pinning the problem on any one bad apple fails to indict the tree from which it fell. While it is convenient to isolate misconduct, targeting an individual only obscures what is truly going on from the scrutiny change requires. The system involves too many players to hold only one accountable for the routine injustice happening in courtrooms across America.

This holds true for Troy Davis’ case and every other case that will come after it. For the purposes of protesting, inflammatory short phrases like “Stop the legal lynching” are catchy but counterproductive. The idea that Troy Davis is innocent means nothing to a judge or jury whose job is to apply legal precedent and interpret the law without influence. If the public wishes to engage in the legal process—intentionally created to be the most removed branch of government—they must use legal arguments.