By: Shuchi Goyal

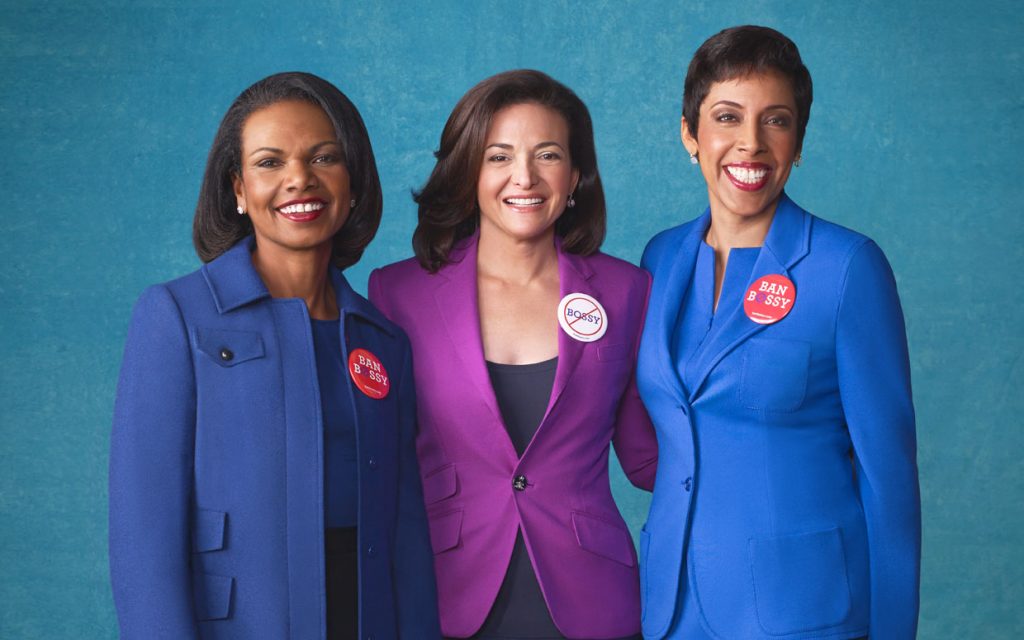

(Credit: Parade)

“Your daughter is creative and constantly engaged around the classroom, but …” My first-grade teacher hesitated, and my parents waited anxiously for whatever horrible truth would be revealed next. “Well … she’s a little bossy.”

It was said as though this was the worst thing a little girl could be: not lazy, not rude, not a bully, but bossy. I was by no means the first girl to hear the word used to describe her personality, not will I be the last. The Oxford English Dictionary’s earliest record of the word being used as it is today comes from 1882, when it appeared in Harper’s Magazine in reference to “a lady manager who was dreadfully bossy.” Since then, it has nearly always been applied to females rather than males.

Too many females become averse to leadership roles while growing up because they are taunted for displaying assertiveness from a young age. In order to bring attention to the stigma of “bossy,” Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg and Girl Scouts of the USA CEO Anna Maria Chávez launched the Ban Bossy campaign in early March 2014. According to the organization’s website, “words like bossy send a message: don’t raise your hand or speak up.” “Calling a girl ‘bossy’ not only undermines her ability to see herself as a leader, but it also influences how others treat her,” wrote Sandberg and Chávez later. The connotations accompanying “bossy” include juvenile, arrogant, or stubborn, and the term minimizes the people it describes; the same can be said for countless other words, such as “shrill,” “domineering,” or even the original b-word, “bitch.” Most people would agree then that these words should no longer be used to demean females. Ban Bossy aims to eliminate words with connotations implying that leadership qualities are incongruous with girls’ personalities.

The campaign goal was initially lauded and garnered attention on social networks through the support of prominent figures such as Condoleezza Rice, Beyoncé, and Jennifer. While Ban Bossy has well-meaning intentions however, its main fault lies in the fact that it struggles to make its methods clear, leaving many people unsure about what action they should take next.

The common literal interpretation of “banning bossy” is problematic. Eliminating one word used to degrade women in power will not eliminate them all, and to “ban” them all is unrealistic. Furthermore, removal of a word will not remove the centuries-old thought patterns and assumptions from society. The unfortunate truth of the matter is that negative stereotypes surrounding bossy women have existed for quite some time, and will probably continue to do so for a while, just as disparaging assumptions about “sissy” men also exist in society. Banning bossy seems like an attempt to sidestep the issue and shield girls from the sad reality that, at least for now, they will likely still face some apprehension from society as they ascend to positions of power. The suggestion to eradicate a word from language for the sake of protecting a certain group sounds slightly Orwellian, and linguists are still in the process of understanding whether cultural differences are causes or reflections of common language.

Sandberg and Chávez are admired not because they had easy roads to success, but because they rose in spite of various obstacles, including the “bossy” jeers; they mastered the art of spinning “bossy” into a positive trait and wielding it as their greatest weapon against detractors. With their campaign, they probably did not intend to actually delete the word “bossy” from speech, but rather take away the negative stereotypes associated with it and redefine it as something more positive. But the target audience of Ban Bossy are young girls who might easily take the instructions too literally and end up frustrated with the virtual impossibility of this task. The Ban Bossy website currently lists numerous resources to help girls become more fearless and seize leadership roles, and Sandberg and Chávez should focus on expanding and publicizing this part of their campaign rather than focusing on the misleading title slogan. Rather than “banning bossy,” they can show girls how to proudly “reclaim” bossy. “If it takes a woman being bossy to become the president, to end violence against women, to destroy rape culture–why not just own that?” said one TIME editor. That was the strategy of Tina Fey, who not only embraced “bossy” but used it in the title of her 2011 autobiography “Bossypants.” And compared to its numerous alternatives, “bossy” is easy to rehabilitate due to its root word, “boss,” which carries far more positive implications.

The Ban Bossy campaign brings up interesting questions: for example, in the 140 years since the birth of the taboo term, how many female leaders were never realized because a girl lost her confidence early from being called “bossy” too often? It is impossible to measure, but most would agree that even one is too many. Ban Bossy has the right spirit, but it would be even better if it channeled that spirit in to ensuring that females will, rather than sweeping “bossy” under the rug, instead use the word to propel themselves forward.