By: Garrett Herrin

“This Congress, they are accustomed to doing nothing, and they’re comfortable with doing nothing, and they keep on doing nothing,” remarked Barack Obama at a 2011 private gathering.

Animosity between presidents and Congresses is as American as apple pie and baseball. In fact, Harry S. Truman nicknamed the 80th term from 1947-49 the “Do-Nothing Congress” and actively campaigned against them as much as he did his opponent in his re-election bid. Sound familiar? Ironically, Truman’s “Do-Nothing Congress” passed 906 bills in its two years, well above current averages (about nine times more than the trend of the current Congress, in fact). What would Truman say of today’s Congress?

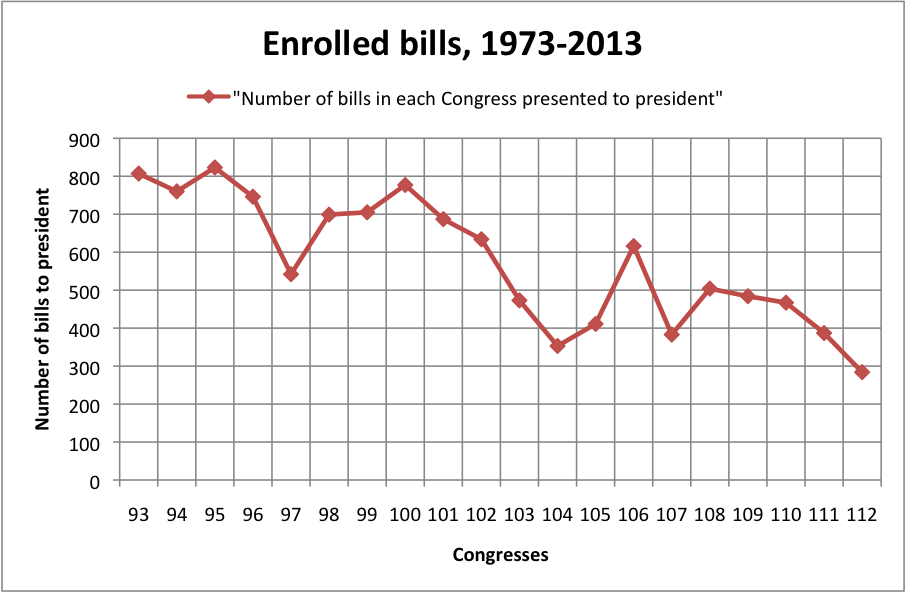

From the 93rd to the 103rd Congress, enrolled bills consistently exceeded 500 per session, with most Congresses producing more than 700. Since the Clinton administration, the number of bills presented to the president has trended sharply downward, with less than 400 in the 111th and less than 300 in the 112th. Congress is currently on-track to worsen its record from the previous two terms. By October two years ago, both chambers of Congress had agreed on and presented 141 bills to the president; in this Congress, that number sits at 39. At the current rate, it will only pass 105 bills, unprecedented in the modern era.

Un-productivity is not necessarily a product of gridlock between the chambers. Even within the House, members of Congress are collectively producing fewer bills and passing a smaller proportion: the 80th House passed 1,739 bills (or 22.8 percent of bills introduced), while the 112th House passed 561 bills (or 8.2 percent of bills introduced), the most unproductive on record. Now by this point, you may be thinking, ‘but Garrett, all these comparisons seem unfair. Aren’t policy goals unique to each period? And won’t the prospect of a bill’s survival in another chamber affect these numbers?’ But in fact, comparing the data from the Vital Statistics on Congress, a joint-effort of the Brookings Institution and the American Enterprise Institute, is fair game because they are each independent samples; the Senate’s composition may affect how the House legislates in terms of political maneuvering, but not the number of bills. Have I beaten the dead horse too much? Good.

Only 14 percent of Americans currently approve of the 113th Congress. 21 percent approve of congressional Republicans; 31 percent, congressional Democrats. But it is important to note that (lack of) productivity in the House is not the sole factor weighing popular discontent. The Senate is as much responsible: just this year, the Senate passed its first budget in four years, but it went nowhere because it included substantial, filibuster-proof tax increases and only modest spending cuts partially offset by increased infrastructure spending. It was a stocking stuffer full of Democratic Party talking points that fails to eliminate a yearly deficit (by 2023, it would be $566 billion) and accrues $5.2 trillion in additional debt.

The House plan, authored by Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wis.), balances the budget by 2023 with deep domestic spending cuts, changes to Medicare, and tax code reform. Sen. Jeff Sessions (R-Ala.), ranking Republican on the Senate Budget Committee, breaks it down: “The singular truth that no one can escape is that the House budget changes our debt course while the Senate budget does not.” But there is a catch: half of the immediate spending cuts in the House budget stem from defunding the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Obamacare); the House budget itself assumes that the law will be repealed and defunded. Neither budget has any chance of passing through Congress as long as the current parties hold their respective chambers. The House budget in particular has no chance as long as Barack Obama is president because even if it were to somehow clear the Senate hurdle, Obama would veto it.

The current standoff in Congress concerns the passage of a temporary spending bill that keeps the federal government open, routine over the past four years (the standoffs as much as the bills themselves). The latest round of congressional ping-pong began when the Senate passed a modified version of the spending bill preserving Obamacare funding, a measure Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) attempted to stop in his 21-hour filibuster. It appeared unlikely that the House would have revisited an Obamacare-related provision in the spending bill; a top House Republican aide said the party planned to make a one-year individual mandate delay part of their proposal to lift the debt ceiling in October. Pressure on Speaker John Boehner within the Republican caucus, though, forced an acceleration of that effort; the House on Saturday added additional provisions to the Senate measure, including the Obamacare implementation delay. That bill is now in the hands of the Senate, and if it fails in the chamber—and in all likelihood it will—they’ll have to compromise with the House bill or send the previous bill back in one last attempt to avert a shutdown. If negotiations fail, the federal government will shut down on Tuesday.

If Republicans want to be taken seriously, they should drop the war on Obamacare that realistically has no chance of succeeding over a Democratic Senate and the current president, and try legislating for a change. If Democrats want to be taken seriously, they should produce a long-term balanced budget; until then, they have no grounds to blame Republicans for gridlock. Neither party will consider anything short of those concessions without which there will be no compromise. We’ll continue kicking the can down the road as both parties play the blame game, debt continues to tower, and legislation becomes a rarer species.