By Aashka Dave and Charlie Spalding

In recent years, politicians have struggled to find common ground on fiscally responsible policy that addresses environmental concerns. President Obama, for instance, upped the political ante by issuing a climate-change ultimatum to Congress during his January State of the Union address. The University of Georgia has not been exempt from this discussion, and has in fact been embroiled in a micro-level environmental dilemma of its own surrounding the continued use of an outdated coal boiler at the University’s central steam plant.

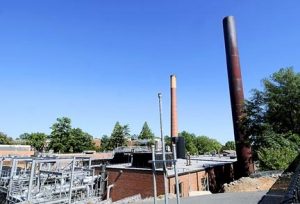

The Physical Plant uses steam production to heat several buildings that occupy the University’s 739-acre main campus. The central steam plant on the corner of Carlton Street and East Campus Road is a fixture of the university’s steam production, and contains four boilers, three powered by relatively environmentally friendly natural gas, and one powered by coal. This coal boiler, used only during the coldest months of the year, is used to create steam that heats some residence halls and hot water for both dining hall washing and lab sterilization. Coal plays a vital role at the university by accounting for 28.5 percent of the steam production on campus.

Coal remains an important fuel in America’s cumulative energy sector as well. According to the United States Energy Information Administration, coal-fired power plants account for 40% of the nation’s energy production. Due to its large scale, the industry is an important provider of private sector jobs, particularly in Appalachia and the western United States. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the coal industry supported around 86,000 jobs in 2011. The coal industry is an important part of the cultural identity of states like West Virginia, where generations of families have mined coal in the Appalachian mountains.

Although coal plays an important role in America and Athens, it is one of the least efficient fossil fuels available. While coal is only used to produce around 40 percent of the nation’s electricity, it is responsible for almost 80 percent of the carbon emissions associated with electricity generation. Every time coal is burned, carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and mercury compounds are released into the atmosphere. In turn, these compounds cause harm to the individuals breathing the air near coal burners and contribute to acid rain. The extraction process itself is also inherently destructive. Strip mining, the most economically efficient mining technique, literally scrapes earth away to reach coal seams, causing soil erosion, chemical contamination of water, and dust and noise pollution. Underground coal mining, the most prevalent mining system, brings large quantities of toxic waste to the surface and lowers the water table.

Student groups like the UGA Sierra Student Organization and its Beyond Coal campaign have been outspoken critics of the university’s continued use of the coal-fired boiler, citing many of the aforementioned environmental criticisms and condemning the exploitative nature of the coal industry. According to Heather Hatzenbuhler, co-founder of the UGA Sierra Student Organization, “In Appalachia, for example, a historically oppressed region, the people are taken advantage of. Coal mining is an industry where the mule has always been more important than the man.” The Beyond Coal campaign has met with a number of challenges, most notably a lack of information and support from members of the UGA community. When students representing Beyond Coal meet with administrators, they often face the challenge of a completely uninformed body. Beyond Coal has also run into the stigma associated with activism. As Hatzenbuhler put it, “activism is a dirty word both among students and administrators…To make people care about something so heavily politicized and related to political ideology has been an incredible challenge.”

Despite these challenges, the campaign has gathered approximately five thousand signatures in the past three years for a petition urging the administration abandon the coal burner. Compared to the petition that resulted in the University’s Green fee, which had signatures numbering in the hundreds, this is a significant accomplishment. However, although the Green fee was implemented with relative ease, the University appears to have disregarded a movement that has garnered far more attention and public support. Hatzenbuhler points to this as proof that the university has no genuine interest in becoming more environmentally friendly.

A 2011 op-ed in the Red and Black penned by Senior Vice President Tim Burgess acknowledges Hatzenbuhler’s environmental concerns by explaining, “the university recognizes that coal is not an optimal fuel source and that its use carries environmental costs.” Despite this conscious awareness of the effects of coal use, the university continues to employ the fuel in its overall energy portfolio due to its cost and dependability. In a fuel source report issued by the Department of Energy’s Southeast Clean Energy Application Center, estimates for capital investment required to replace the coil-fired boiler “are in the $20-26 million range.” With a weak economic recovery and cuts in state funding, replacing the coal boiler is simply not financially feasible. The energy needs of a burgeoning research campus like the University of Georgia are also a significant factor in the administration’s decision to continue operating the boiler. In order to continue to rise to the highest echelons of educational institutions, the university must maintain a dependable source of energy for laboratories and dormitories alike. At this point in time, it seems as though administrators are willing to take the “heat” for an environmentally unfriendly process in return for continued expansion and increased prestige of the university.

It is also important to note that the University, despite having added four million square feet in the last decade, has reduced its energy consumption per square foot and is well on its way to a 20 percent overall reduction by 2020, as outlined by the university’s Strategic Plan. All new construction projects are required to receive a silver Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification, and the retrofitting of existing buildings, like the Jackson Street College of Environmental Design, has focused on renewable materials and solar panels.

Despite the university’s efforts, environmental advocates like Hatzenbuhler remain unsatisfied. In fact, Hatzenbuhler argues that the solar panels generate minimal electricity for the Jackson Street Building and sat in a warehouse for a length of time before they were installed. Administrators did not want to put the panels on the initially proposed building – the University Bookstore – because they feared the panels would be too visible on such a central part of campus.

Ultimately, Hatzenbuhler acknowledges that the efforts the University is making are steps in the right direction. Compared to the efforts made by other institutions, however, and the potential that the University has to be a leader in the field of sustainability in education, advancements are few and far between. University officials are faced with the unenviable task of allocating the increasingly limited resources of the school in a process that inevitably leads some interest groups to cry foul. Perhaps as green technologies become more affordable and Georgia addresses its economic woes, the University will undertake more extensive sustainability efforts. In the meantime, the voices of students like Hatzenbuhler are integral to ensuring that the University honors its commitment to the environment in the fullest degree.