By: Tia Ayele

In a televised interview alongside Zambian president Rupiah Banda, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton warned Africa of neocolonialism, stating:

“Investments in Africa should be sustainable and for the benefit of the African people. It is easy – and we saw that during colonial times – to come in, take out natural resources, pay off leaders, and leave. And when you leave, you don’t leave much behind for the people who are there. You don’t improve the standard of living. You don’t create a ladder of opportunity.”

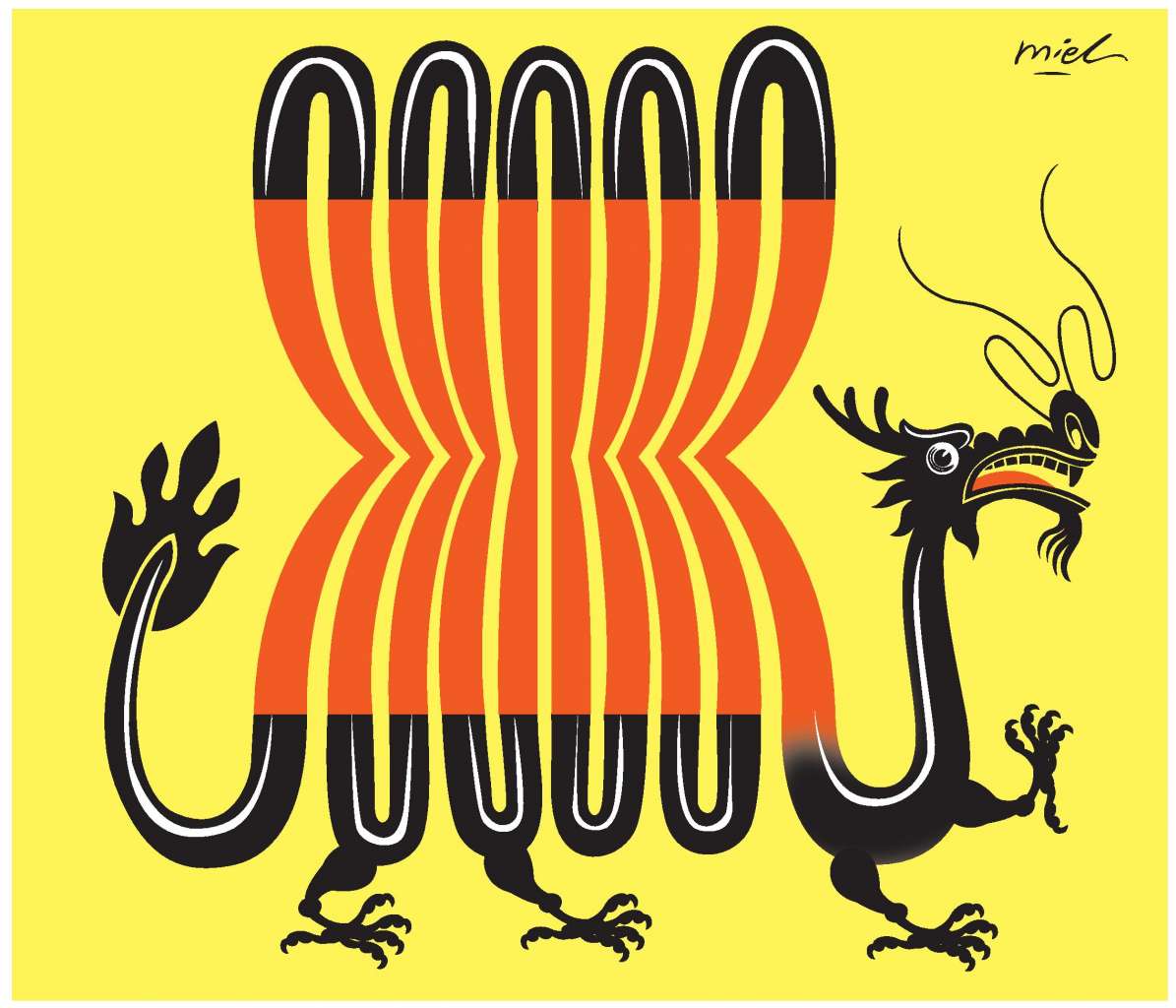

Clinton’s admonition to Africa is one that is continually repeated to African leaders, as emerging foreign investors are making their way to the developing continent. Among the many countries that are eyeing Africa’s rich resources, China is ahead of all of them, engaging in over $50 billion in trade with Africa, according to the IMF. Although these funds have resulted in many developments, including the construction of new schools and hospitals, the influx of Chinese expatriates has sparked mixed feelings among the African people. With complaints of exploitation and corruption, it has yet to be deciphered whether the relationship between China and Africa is mutually beneficial. Is it, as Clinton stated, “a ladder for opportunity,” or is it just another form of neocolonialism?

Many Africans will admit that China has done more to fight poverty in Africa than any other foreign country. The IMF reports that, in the past five years alone, China has reportedly contributed over $6 billion towards more than 800 aid projects in Africa. Tsegab Kebebew, a senior official in Ethiopia’s foreign ministry, speaks highly of the budding Sino-African relationship, “This is a new strategic partnership. There is no colonial history between Africa and China, so they are well received here,” he told the BBC. “There is no psychological bias against the Chinese.” However, what Kebebew fails to answer is whether a lack of psychological bias is enough to prevent Sino-African relations from souring. Complaints of Chinese infiltration have already been giving way in all parts of Africa, and many Africans have expressed their distrust of the foreigners.

The contempt for these Chinese expatriates first stems from the Chinese’s’ notoriety for poorly constructed infrastructure. For example, the highly anticipated Chinese-constructed hospital in Angola was forced to close down after only a few months due to cracks in the walls. Similarly disappointing, 81- miles of Chinese built roads across Zambia were soon swept clean by rain as a result of poor construction. Common stories like these contribute to China’s deteriorating reputation in Africa.

The increasing distrust of Chinese investors in Africa is also intensified by the obvious competition that these investors beget. African entrepreneurs and business owners often find difficulty in competing with the cheap costs of Chinese products, leading in the collapse of many local industries. Envrionmental issues have also arisen, as the Chinese have been accused of despoiling several ecosystems in local African villages.

Africa’s very economic exchange with China is suspiciously similar to that of colonialism. One could argue that the very practice of exporting rich African raw materials in exchange for cheap Chinese manufactured goods is too reminiscent of European mercantilism. As a solution to this, the African Development Bank Chief Economist, Mthuli Ncube, told Voice of America that he advises China to create more partnerships with local communities: “I advise them that it is important for foreign investors to work at these joint ventures [as] a way of stimulating local innovation.” Though Ncube asserts that Sino-African relations are generally positive, “I think [that] largely the investments have been positive. They have created jobs and I welcome these new industrial parks.”

Whatever the relationship may be between Africa and China, it is evident that Chinese interference has prompted industrialization across the continent. As a result of these investments, countries all throughout Africa have followed China’s lead in bolstering their economies, with six out of the ten fastest growing economies currently located in Africa. The proliferation of Chinese investors has undoubtedly spurred new markets of African exports; between 2000 and 2009, Africa’s total trade shockingly rose from $247 billion to $673 billion (The Africa Report). This sort of growth is unprecedented in Africa.

Although far from purely altruistic, Chinese investments in Africa appear to be focused on development. Contrary to the European “investors” of the past, the Chinese have proven to want more from Africa than to simply plunder its natural resources, as they are financing sustainable commercial investments that have been improving the overall standard of living in Africa. Nevertheless, their exact “wants” are still in question for many of the African people. Conclusively, it is a fair assumption to state that the nature of Sino-African relations is not exploitive or completely symbiotic. However the relationship may be construed, the Chinese are offering sorely needed investments to the developing continent and are surely offering a “ladder of opportunity” to African countries.