Boris Nemtsov walked with a woman down a busy sidewalk on Bolshoi Moskvaretsky Bridge at 11:30p.m. on February 27. A single security camera watched their stroll. At 11:31p.m., a snowplow drove towards the pair and stopped alongside them, obstructing the camera’s view. Behind the snowplow, Nemtsov was shot four times in the back.

The snowplow moved forward, revealing Nemtsov’s body lying on the sidewalk and his panic-stricken companion running for cover, the surveillance footage shows. Boris Nemtsov, former deputy prime minister of Russia and leading critic of Russia’s war in Ukraine, was murdered just outside the Kremlin only two days before he was supposed to lead a protest march against Russian action in Ukraine.

Nemtsov’s murder was undoubtedly state-sponsored. The snowplow (deployed by the city government) appeared on the bridge despite the fact that there was no snow in Moscow the night Nemtsov was killed. The vehicle obscured Nemtsov from the view of the security camera, meaning the killers knew where the camera was. It took police 11 minutes to arrive on scene despite the fact that Moscow is littered with police officers. When police finally did arrive, they cleaned the crime scene. The police detained Nemtsov’s companion, a Ukrainian woman named Anna Duritska, and they still have not allowed the eyewitness to leave their custody.

Furthermore, Nemtsov’s murder was most likely ordered by Russian President Vladimir Putin. Odds are slim that a plan as intricate as this carried out with such a high level of state assistance and in such close proximity to the Kremlin could have escaped Putin’s attention, let alone succeed without his approval. It also matches the modus operandi of several other political assassinations during the Putin era, including Galina Starovoitova, Sergei Yuschenko, Anna Politkovskaya, and Alexander Litvinenko.

Galina Starovoitova was a pro-West, liberal reformer under the late Russian President Boris Yeltsin, and she warned that whoever succeeded Yeltsin may become a dictator. She was shot dead outside her apartment in Moscow in 1998. Sergei Yaschenkov was a liberal politician who co-chaired the Liberal Russia Party. He was shot dead outside his Moscow apartment in 2003, hours after his party had been registered by the Justice Ministry to run in that year’s parliamentary election, making him the ninth member of parliament killed in a nine year span. Anna Politkovskaya was a critic and investigative journalist exposing human rights abuses in Russia’s war in Chechnya. She was shot dead outside her Moscow apartment in 2006. Alexander Litvinenko was an ex-KGB agent who defected and became a British citizen. He was poisoned with a radioactive isotope in London in 2007. It took him two weeks to die.

Nemtsov’s killing fits the profile of these other murders. The fact that Nemtsov was killed on a busy street instead of outside of his apartment may have been a way to send a more explicit message to Putin’s detractors. Nemtsov’s death, like the other deaths during Putin’s tenure, benefits Putin directly and intimidates a segment of his opposition, as Forbes contributor Paul Gregory explains.

“The Politkovskaya murder signaled to reporters not to touch stories about atrocities and crimes against humanity in Chechnya. The Litvinenko murder told defectors with intelligence information they are not safe, even in England. Now Nemtsov’s killing tells opposition figures that the days of soft repression (beatings and jail) are over. If they want to continue their protests, they are risking their lives. Death can strike them at any moment, even on a crowded street.”

Another indication that Putin ordered a hit on Nemtsov is the use of his standard spin machine to divert suspicion from himself. This diversionary tactic is the third of three steps that Eurasian specialist Paul Goble believes Putin follows when eliminating his opposition. “First, Putin marginalizes his enemies, then he or his allies kill them, and then he muddies the water by putting out multiple versions of what happened, confident that few will connect the dots and hold him responsible.”

Putin has certainly muddied the water since Nemtsov’s murder. Sources close to the Kremlin first suggested that agents of the West killed Nemtsov to throw suspicion on Putin and ignite unrest in Russia. Then, the theory became “fascist” Ukrainians did it to frame Putin. Next, it was Chechen Islamist fundamentalists who killed Nemtsov for supporting Charlie Hebdo, the French satirical paper that was attacked by Islamic extremists. Yet another theory said the Chechens were Ukrainian mercenaries. The theory has further evolved now to being the Chechens acting alone and out of personal hatred for Nemtsov.

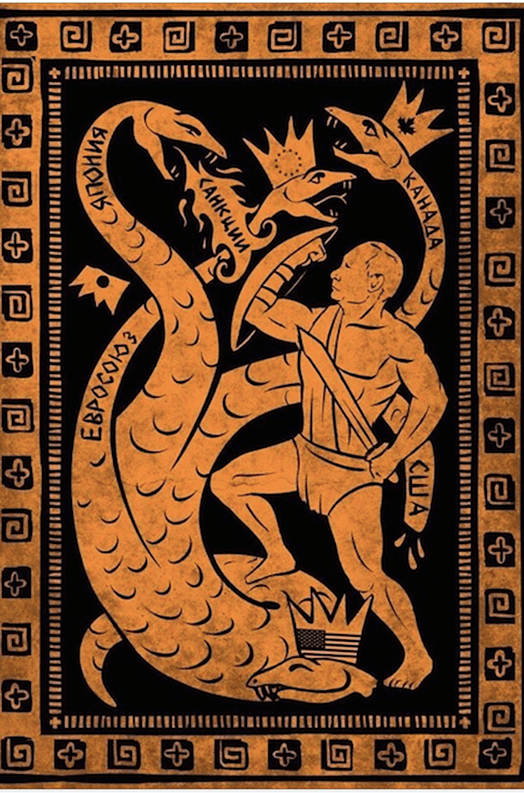

All of Putin’s conspiracy theories shift the blame to an external actor that Putin is already attacking. This deflects suspicion from him, stirs up support for Putin’s attacks against the scapegoat, and paints Putin as the stalwart guardian of Russia.

“(Putin’s success) is simply unthinkable without hatred, and the entire history of Putin’s Russia is the history of capably directed hatred towards various individuals, social groups, countries, and nations,” wrote Ilya Milstein. “First there were the Chechens, then the oligarchs with their television channels, later the Georgians, now the Ukrainians, Europeans, Americans, and always those who disagree.”

As long as Putin can externalize the enemy, the Russian people will want Putin’s protection. If there are Ukrainian fascists attacking Eastern Ukraine, then he can justify annexing Crimea to protect ethnic Russians from the threat. If there is a Western conspiracy to encircle Russia, then he can justify attacking Georgia and Ukraine for trying to join the EU. If Islamist radicals commit murders in Moscow, then he can justify repressing Muslims in Chechnya. It should come as no surprise then that the Russian media’s list of suspects for Nemtsov’s killing consists of Ukrainians, Westerners, and Islamic radicals.

Putin is convincing Russians that the problems Russia faces are everybody else’s fault. By necessity, this means that the Russian people are not putting any blame on Putin or his government. In fact, Putin’s approval rating was polled at 86 percent this February.

Nemtsov may yet undermine some of Putin’s domestic support. Other Russian opposition members will publish in April a report Nemtsov had been writing before his death that detailed Russian involvement in Ukraine, titled Putin and the War. According to Yevginia Albats, a friend of Nemtsov for 27 years, it will explicitly identify Putin’s government as the cause of the violence in Ukraine.

“He didn’t pretend as if it was a civil war inside the Ukraine or that the United States and Russia are conducting a proxy war. He was absolutely damn clear that Russian Federation is running and conducting a war against Ukraine, that it’s sending weapons and it’s sending soldiers to fight the war in the Eastern Ukraine.”

This report is a fitting end to Nemtsov’s long service in Russia’s opposition. The last words readers will find from Nemtsov will be calling out Putin on one more lie.