By Torus Lu

Recently, Senate Republicans passed a quintessentially-Republican budget resolution. It involved large spending cuts to government programs, which its proponents promoted by talking about cutting taxes. Senate Democrats, of course, focused criticism on the spending cuts

Since spending cuts have leave a significant amount of room in this budget resolution, $1.5 trillion tax cuts (over ten years) will be allowed to be passed through the budget reconciliation process, which is a set of Senate rules allowing fiscally-oriented legislation to pass with just a simple majority. This is highly significant, as a major barrier to Republican legislative goals has been the fact that they hold 52 of the 100 seats in the Senate – a simple majority if they are united on the relevant vote, but insufficient to pass the 60-vote threshold generally needed for legislation.

President Trump tweeted eager anticipation for tax reform, praising the passage of the budget resolution. Some conservative House Republicans ceased their push for deeper spending cuts in order to provide a unified front in favor of tax reform. Given that major changes to the federal tax code may be coming, it seems it would be important to know what those changes entail. The Treasury has outlined several guiding principles for the president’s tax reform policy.

Before going into the details of the president’s tax plan, several things should be noted. This article is heavily reliant on analyses by the Tax Foundation, which is a think tank that generally advocates for reducing taxes. Most of the cited impacts on total revenue come from dynamic analyses, which seek to model the effect of tax reform on economic behavior and measure the changes in taxes paid, assuming behavior stays constant. Moreover, revenue impacts are projected over ten years. For a frame of reference, the Congressional Budget Office projects that the federal government will take in $62 trillion of tax revenue over the next ten years.

Income tax changes

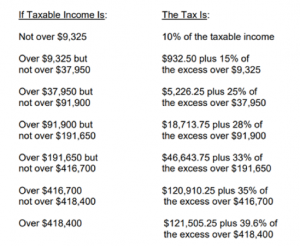

The first of the tax reform proposals is a consolidation of the current income tax brackets. Income taxes currently work by splitting income into multiple different brackets, each of which gets a different rate. For 2017, single filers’ income tax brackets will look like this:

Other types of filers will have different bounds on their brackets. For example, married couples filing jointly have a first bracket extending up to $18,650 instead of $9,325. However, every type of filer will have seven brackets with rates of 10%, 15%, 25%, 28%, 33%, 35%, and 39.6%.

The president’s proposal condenses the current structure into three brackets of 12%, 25%, and 35%. Additionally, the proposal suggests there may be a fourth bracket added to prevent wealthy filers from paying less. It is unclear where these brackets will begin and end, and there are many other considerations involved in determining how much someone pays in income taxes.

Given that information on brackets is not provided, it is unclear how this will affect revenue. It should also be noted that these proposed rates have changed many times. At one point, Trump had campaigned on deeper cuts to income taxes during the campaign. The tax plan released then featured 10%, 20% and 25% rates and much more generous brackets than the current structure. Released shortly before the election, a newer tax plan featured rates of 12%, 25%, and 33% and information on where these brackets began and ended. An analysis of that plan by the Tax Foundation found that such changes to income taxes would reduce revenue by $1.2 trillion over 10 years.

Deductions and Credits

One reason why the income tax brackets don’t tell us everything about how tax burden and revenue will change is that tax credits and deductions also affect both bottom lines. A tax deduction allows taxpayers to reduce the amount of income that is subject to taxes. A tax credit allows taxpayers to directly reduce the amount of taxes owed. Examples of these include the standard deduction and the Child Tax Credit. The former is a general deduction that every taxpayer is allowed to use as long as they do not use the specific deductions. The latter allows taxpayers to reduce their taxes for each child in their family, with wealthier taxpayers getting a lower credit.

The President’s tax plan doubles the standard deduction and increases the Child Tax Credit. It also calls for the elimination of most specific tax deductions. That last part is vague, and may include deductions for medical expenses and state, local, and foreign taxes. The elimination of deductions for state and local taxes has been a particularly controversial point, as it will disproportionately impact states with high taxes, e.g. New York, New Jersey, and California. Politicians from those states, including Republicans, have therefore criticized this move. This portion of the plan is intended to make taxation fairer, and it could also have the effect of making filing simpler. Additionally, the elimination of deductions may also increase revenue by widening the tax base.

Other Taxes for Individuals

The President’s tax plan also eliminates the estate tax, which is a tax on inheritances larger than $5.6 million. Republicans have campaigned on elimination of the estate tax for a long time, derisively calling it a “death tax”, and suggesting that it harms small businesses and farms. Proponents of the estate tax often point out that vast majority of estates are not subjected to the estate tax because they fall below the threshold. Additionally, estate taxes reduce the accumulation of inherited wealth, which proponents view as a favorable effect. Either way, its elimination is will reduce revenue, but not by much. The Tax Foundation’s analysis found that eliminating the estate tax would reduce revenue by $24 billion over 10 years.

The alternative minimum tax is a second method of calculating taxes. Should the amount owed to the government come out larger than the tax owed under the regular income tax system, taxpayers must also pay the difference. The President’s tax plan regards the alternative minimum tax as unnecessary complexity, and therefore calls for its elimination. The Tax Foundation analysis finds that this would reduce revenue by $428 billion over ten years.

Taxes on Business

The President’s tax plan also calls for many changes to taxes on business. It limits taxes on non-corporate businesses to 25% and cuts the corporate tax rate to 20%. Proponents of the plan content that high taxes on business are responsible for stifling investment and preventing competitiveness. Like individual tax cuts, corporate tax cuts have been an objective of Republicans for a long time. However, corporate tax cuts have also received some support from the other side of the partisan divide. In a compromise move, Barack Obama offered to cut the corporate tax rate to 28% and end certain deductions during his time as president, but nothing came of it. This is not to say that corporate tax cuts are uncontroversial – some critics have regarded these proposals, like the individual tax cuts, as attempts to redistribute income to wealthy individuals and large corporations. A Tax Foundation analysis (separate from the one mentioned previously), found that a corporate tax cut to 20% would cost $645 billion in revenue over ten years.

These principles are inherently aspirational, and any finalized tax reform will be unlikely to fulfill all of them completely. Still, they provide clarity with regard to the type of tax reform Republicans are pursuing.