By: Andrew Roberts

By: Andrew Roberts

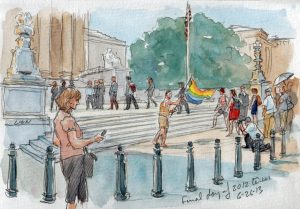

The United States is heading down the road to marriage equality. It’s a windy, long road, but one that is inevitable. The path to marriage equality was further paved this past month when a Texas federal district judge struck down a voter-approved ban on same-sex marriage. The choice is clear: Either board the bandwagon heading down the trail or be trampled by the constitutional jurisprudence that emanates from what Alexander Hamilton once called “the least dangerous branch.”

The Supreme Court’s shift in its view toward this hot-button issue occurred in 2003. Before then, its most conclusive decision came in Bowers v. Hardwick (1986). The majority (a slim one, to be clear) said that the Constitution did not include a “right of privacy that extends to homosexual sodomy” and that it does not support a “fundamental right to engage in homosexual sodomy.” This decision ultimately upheld a Georgia sodomy law which criminalized homosexual sodomy.

Then, in Lawrence v. Texas (2003), the Supreme Court made a landmark swing in the opposite direction. When looking at a functionally similar situation in Texas, the Court struck down a sodomy law that criminalized same-sex sexual activity and explicitly overruled Bowers by an even larger majority than the thin majority that had originally upheld the Georgia sodomy law. The Court, in this important line, reversed the course of the nation when it said:

The State cannot demean their existence or control their destiny by making their private sexual conduct a crime. Their right to liberty under the Due Process Clause gives them the full right to engage in their conduct without intervention of the government.

This direction has continued ever since, with recent landmark decisions in 2013. Exactly ten years later—to the day—from the Lawrence decision, the Court released two decisions in Hollingsworth v. Perry (2013) and United States v. Windsor (2013). In Hollingsworth, the Court decided not to decide the case, as one of the parties lacked appellate standing. In other words, since it was the proponents of the debated Proposition 8 referendum, which banned same-sex marriage, who appealed the case after the State of California decided not to defend it, the Court said it was not their case to argue. By making this decision, the Court reverted back to the district court decision, which had overturned Proposition 8, functionally allowing same-sex marriages to continue.

Windsor was a different story. Unlike Hollingsworth, in which the Court refused to definitively rule on state-banned same-sex marriage, the Court in Windsor answered the question directly: Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act—which defines marriage as a legal union between one man and one woman—“violates basic due process and equal protection principles applicable to the Federal Government.”

The Court, of course, had sound constitutional reasoning for its decision in support of marriage equality rights. As a violation of the Fifth Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection, the Court’s argument is best summed up in its final words of the majority opinion in Windsor:

DOMA singles out a class of persons deemed by a State entitled to recognition and protection to enhance their own liberty. It imposes a disability on the class by refusing to acknowledge a status the State finds to be dignified and proper. DOMA instructs all federal officials, and indeed all persons with whom same-sex couples interact, including their own children, that their marriage is less worthy than the marriages of others…By seeking to displace this protection and treating those persons as living in marriages less respected than others, the federal statute is in violation of the Fifth Amendment.

Whether one supports marriage equality or not, this eloquent quote shows a passionate defense by the Court. While there is clearly some legal reasoning to its decision, one must ask why the logic applied in Windsor was not applied in Bowers. Georgia sought to alienate and forbid sexual acts by consenting adults, which, in the words of Windsor, singles out a class, imposes a disability, and implies that homosexuality is less worthy.

The reasoning behind this rather quick flip-flop likely comes from two things that are far more prominent than a constitutional argument: A change in the members on the bench and the Court’s ear for public opinion. The Court during Bowers was more conservative, and included members such as recently appointed William Rehnquist, who was known for his conservative decisions. Further, the Court has been known to listen to public opinion when making decisions, even though the life tenure of justices is intended to be a check against this influence. In 1996, for instance, only 27 percent of the United States supported same-sex marriage, as opposed to 54 percent in 2013.

Important decisions by the Supreme Court likely take into account not only public opinion on the issue and the Justices’ personal ideology, but also a degree of sound constitutional reasoning. That being said, since Bowers, the Justices have either begun to use more canny reasoning or are simply more tolerant; otherwise they would have applied the logic used in Windsor to the question at hand in Bowers. As more decisions like the one in Texas occur and contradict one another, the Court will soon be forced to answer the question of state-banned same-sex marriage once and for all.