By Bennett Souter

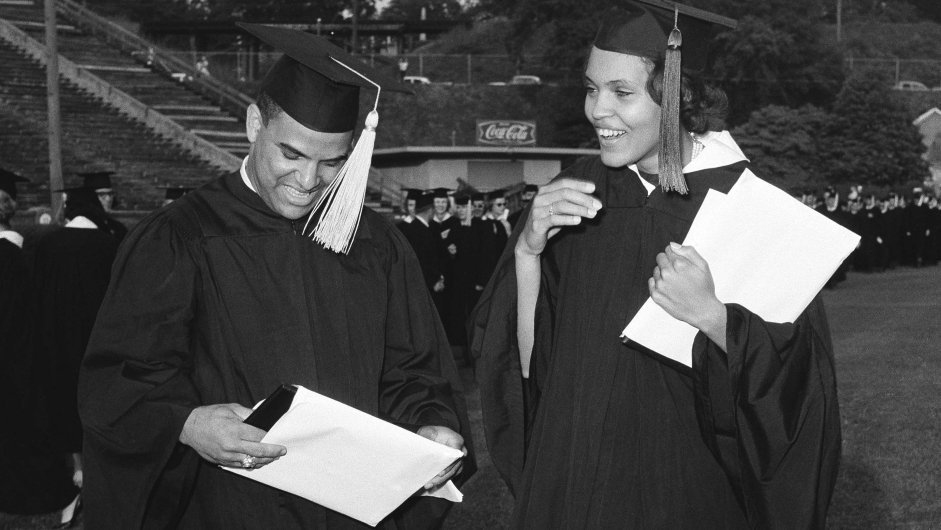

In the midst of a new, confusing political regime, 2017 has actually served as an uplifting reminder of how far our state has come since the Civil Rights era of the 1960s. With Black History Month just now commencing, we are called to look back at a time when equality was not guaranteed to every member of society. By honoring those who fought for change, students can also find courage in tackling modern day discrimination. January 9, 2017 marked the 56th Anniversary of the admittance of the first African-American students to the University of Georgia. On that day, Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes were admitted to the University and have since gone on to accomplish a multitude of successes. Keeping this in mind, it is important to survey the context of the times and an important decision that one Georgia governor had to make, but most importantly, what this anniversary represents now.

Following the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, the South was faced with a pivotal question: would the states integrate their schools “at all deliberate speed” or would they exercise all their power to prevent the progressive transformation? In response to this new issue, demagogues of the era campaigned heavily to promote drastic ideas and techniques to block integration in their states. In 1959, the state of Georgia elected Democrat Samuel Ernest Vandiver Jr. as its sixty-third governor. Despite running on the slogan, “No, not one,” which implied that not one school would be integrated, Vandiver’s strict views on segregation shifted dramatically as the University of Georgia desegregated relatively peacefully during his time in office.

In the wake of the 1961 New Year, Governor Vandiver faced a serious dilemma in the ongoing education crisis, a case that would determine the fate of Georgia’s flagship university. Having been denied admission to the University of Georgia due to “limited facilities,” plaintiffs Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes filed suit against the University’s registrar, Walter Danner, on September 2, 1960. Judge William Bootle, Chief Judge of the United States District Court for the Middle District of Georgia, found the two plaintiffs fully qualified for immediate admission to the University of Georgia and concluded that they would have already been admitted had it not been for the color of their skin. On January 6, 1961, Bootle’s ruling stated, “It is further intent of this injunction that the defendant and other persons above indicated are herby enjoined from refusing to permit the plaintiffs to enroll in and enter the said University as students therein immediately for now beginning Winter Quarter, 1961.” [i]

In order to prevent the University from closing, Bootle issued an injunction forbidding Vandiver from cutting off funds to the school. The students registered for classes on January 9, 1961, and they were enrolled on January 11, 1961. That night a demonstration broke out in front of Mr. Holmes’ dormitory. Despite having quelled the demonstration by 12:00 a.m., UGA President Omer Aderhold suspended the plaintiffs from the university out of concern for the students’ protection. At the hearing on the suspension of university funds, Bootle ruled the 1956 Georgia laws denying state money to integrated schools as unconstitutional. The next day, Bootle reinstated plaintiffs Holmes and Hunter to the university for the following Monday.[ii]

This provided Governor Vandiver with two choices: a direct defiance of a federal court order or an acceptance of public integration. Years later in an interview, Vandiver discussed the cultural impact of closing the University of Georgia. Vandiver understood that almost everyone in Georgia had a significant tie to the university in one way or another. While most people did not want to see the school integrated, they also did not want to see their flagship university closed. “If they had brought it against Tech,” Vandiver related, “the feelings from families wouldn’t be as strong. The people in Georgia did not want that university closed. They did not want it integrated either, but they didn’t want it closed.”[iii]

Vandiver, like those running before him in the wake of the Brown decision, was primarily elected because of his efforts to oppose integration. It is not assumed that Vandiver, nor any other candidate, believed that he would have to face the treacherous question of desegregation during his time in office, but nevertheless he did. Thrown into one of the most turbulent times in Georgia history, Ernest Vandiver was faced with a paramount decision: preserving public education at the cost of integration or closing the system down for the continuation of a dying practice. Despite the political suicide many believed he committed, Vandiver will now and always be remembered for choosing to fall on the right side of history.

With this in mind, the state is now faced with a more subtle form of discrimination. Athens, Georgia with more than one hundred bars within its proximity is notoriously known for denying African-Americans admittance to its many drinking establishments. Rob Oldham explains in “Going Out, But Not Getting In,” the reasons for the scarce number of blacks found in most Athens bars. By using biased dress codes and commonly used excuses such as “private parties only”, bars have successfully been able turn away the black student populous. This problem currently does not have a suitable fix, with the language of Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights Act not clearly applying to bars. And while our state still faces such cases of discrimination, this anniversary serves as a representation of courage that can be used when facing racial adversity in the present.

The 56th anniversary of Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes being admitted to the University is not only a positive reminder for Black History month, but it should also be viewed as motivation for a continuation of equal treatment. Holmes and Hunter pioneered the way for equality at this University and serve as role models for everyone. It is up to the present student population to follow their lead and continue to strive for an end to discrimination, including the Athens bar scene. 2017 is undoubtedly a year of uncertainty, but it does not have to be a year of negativity.

[i] Vandiver, S. Ernest 1918-2005. S. Ernest Vandiver Papers, I. Governor’s Office Files. Mixed Material

[ii] Roche, Jeff. Restructured Resistance: The Sibley Commission and the Politics of Desegregation in Georgia. Athens: U of Georgia, 1998. Print.

[iii] Henderson, Harold P., Ellis Gibbs Arnall, and S. Ernest (Samuel Ernest)